Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet was not written in some faraway, mysterious land, as one might assume from reading it. Almustafa, Almitra, and the people of Orphalese did not emanate to life in some lonely hermitage on the top of a mountain, but – unbelievable as it may seem – in a bustling and sometimes "lively and festive” estate in the countryside of Massachusetts, USA.

By Francesco Medici and Glen Kalem-Habib

In the spring of 1918, Gibran accepted an invitation to come and stay at a retreat at Boston writer and poet Marie Garland’s Bay End Farm in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts. Surprisingly, he found he could focus and eventually work undisturbed in a setting that would lay down the first draft of his masterpiece.

Marie Tudor Garland (1870-1949), a widow of ten years, was an ardent feminist who had six children. In the early 20th century, she commissioned for a number of prefab cottages to be delivered and erected on her property with the aim of offering many artists and authors a sanctuary to relax and work whilst enjoying her hospitality – regular visitors, among others, were Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942), Rose O’Neill (1874-1944), Witter Bynner (1881-1968) and Haniel Long (1888-1956), who were part of Gibran’s entourage.

In a letter dated April 10, he wrote to his patroness Mary Elizabeth Haskell (1873-1964) about the farm and its owner. The elated letter also mentions his enthusiasm towards writing The Prophet:

I am leaving New York on Friday the 12th for Buzzards Bay to visit Mrs. Garland. I think I told you something about her while you were in New York. She is indeed a very wonderful and a very real friend. I am to have a house all by myself with (all comforts of home): and if I can work there – as well as rest – I shall surely stay more than a few days. Mrs. Garland wants me to stay a long time, as long as I possibly could. But of course I can only accept so much from such a generous person. After the visit I want so much to go to Boston and see you and my sister. […] I have not been able to do much work in the studio [New York]. […] But I have many ideas which I hope to execute while in the country. One large thought is filling my mind and my heart; and I want so much to give it form before you and I meet. It is to be in English – and how can anything of mine be really English without your help?

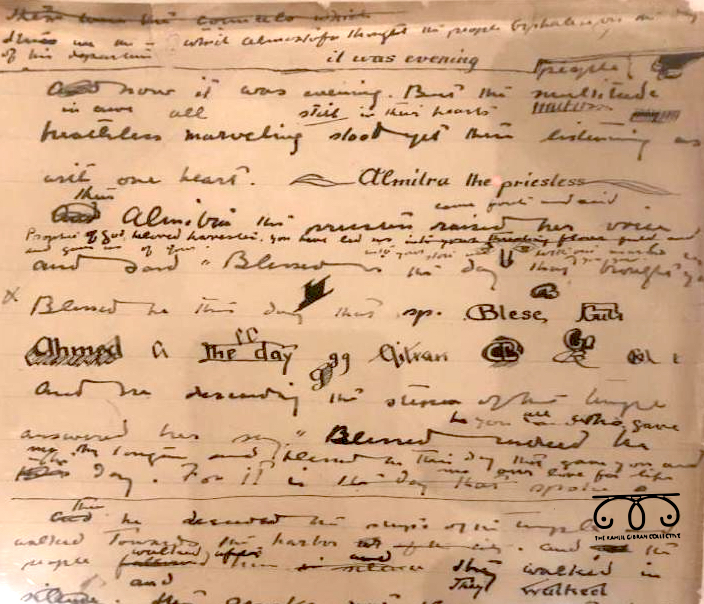

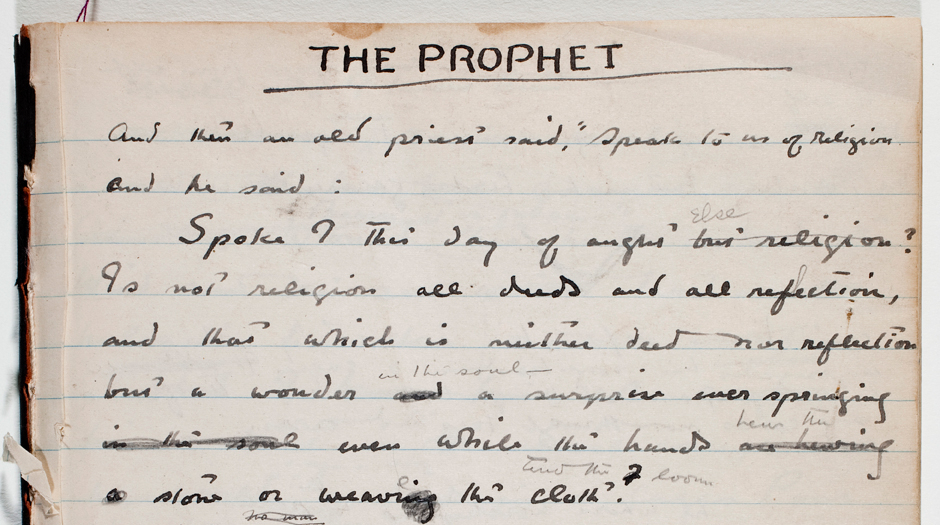

We do however know that The Prophet was manifesting in Gibran’s mind much earlier. Since 1912, Kahlil had mentioned to Mary of his “one large thought” which went by the working title of The Commonwealth. But it was during the twenty-four days he spent at Bay End Farm, in 1918 he finally wrote the first draft, which was aptly renamed The Counsels – it was in June 1919, when the work took on its final title and once again renamed as The Prophet.

In the years of the First World War, Gibran was directly involved with various Syrian-American political organizations, such as the Syrian-Mount Lebanon Relief Committee, the Syria-Mount Lebanon League of Liberation and the Syrian-Mount Lebanon Volunteer Committee. It is therefore not surprising he needed a break far from New York, to come back to devote himself to his

art. On April 14, 1918, he wrote to Haskell from Buzzards Bay, Cape Cod: «This is such a wonderful place and Mrs. Garland is a remarkable hostess as well as a rare and a real being. I would like to stay here forever!! because I am free to be what I want and to do as I like. And I feel that I shall be able to do some good work». Three days after, she replied with all her enthusiasm: «To think of you on the Cape at Mrs. Garland’s is a sweet thing every day – and a wonderful thing. […] And I am so much more than happy, K.G., that you have this season with your painting and writing». In those same days he wrote to his sister Marianna: «I am a royal guest in a royal house in a royal countryside. I can work here, ride horses and can drive the auto whenever I want»[1].

When Gibran and Mary Haskell met on May 6th, 1918, she found him «marvelously well – solid, browned, bright-eyed and unnervous, unworn». He first told her about his stay at the farm, how he had felt free to wander by the seashore and freshwater pond or watch the Welsh ponies, sheep, and forest animals, and how the presence of Mrs. Garland’s family of six, and her eight adopted children, created a lively, festive atmosphere:

I’ve had a glorious time. I felt like work and was able to do it. It was a wonderful place, and Mrs. Garland is a remarkable being – so full of energy and with a splendid sense of justice. A worker – helps wash dishes if help is needed; helps to cook if that is needed; is a tailoress and seamstress and writes, too – has written two books. Her boys, the three of them, were back from college for their vacation – splendid beings. They worked on the farm – everybody worked. There were a lot of boys on the farm last summer beside the Garlands, making money and eating well and having a fine time with eight hours work a day and the rest of the time for all sorts of things. […] One of the things I admire most in Mrs. Garland is the freedom she gives others. With the boys, for instance, she tries to learn from them instead of teaching them. She means everything in that community of two thousand, and everything that can be saved for the government is saved – every grain of wheat or rice or other food – every plate at table is cleaned. She eats all that is on her own and in the nicest way has everybody else doing the same way. And money is not wasted – nothing is wasted – though there is so much. It is all put to use. In the morning Mrs. Garland and I might have breakfast together because the others had gone off a little earlier – we might be at 8 and they have been off at 7. Coffee and a few little things would be brought in and when breakfast was over she might begin to write and I’d begin to write. And if after a while I wanted to go up to my room, I could do it without even saying anything. […] No, I didn’t stay in one of the little houses – Oh! there are so many of them on the farm, and she keeps them for her guests. It was too cold, so I stayed in the big house. But I could work perfectly well.

Although he had no time to paint, he did make a pencil sketch of his hostess. Among Marie’s six children, he was captivated especially by her daughter Hope, to whom he also had a ‘double’ portrait – full face and profile:

The daughter, Hope, fourteen years old, has a great gift with her hands – for drawing, and even more for modeling and especially modeling animals. She has an eagle there, for instance, and the head of a bull, that are real beings.

Years later, Gibran’s joyous and productive stay at the farm was further captured, in an interview on July 24, 1971 by the author’s biographers, his namesake cousin Kahlil George Gibran (1922-2008) and the latter’s wife Jean. Mrs. Hope Garland Ingersoll (1905-2001), who was 66 at the time, recalled that Gibran made a roseleaf cake with the children and spent time discussing and looking at their artistic efforts. It was she who renamed Bay End Farm into Grazing Fields Farm, as it is known today.

It was at that same meeting on May 6th, that Gibran for the first time showed Mary Haskell the result of what he called the “one large thought” and on which he had meditated while wandering through the wooded property and along the edge of the sea:

I did about 2/3 of the big piece of English work I wrote you about. It has been brooding in me for 18 months or more, but I’ve had the feeling that I wasn’t big enough yet to do it – and I’d just let it wait. But in the past few months it has been growing and growing in me and I began it. It is to have 21 parts, and I’ve written 16 of them.

Then he described the prologue and read her the chapters on children, friendship, clothes, eating and drinking, talking, pain, marriage, death, time, buying and selling, teaching and self-knowledge, houses and others. That same night they began to make «very slight needed changes», thus inaugurating the first working session on what would become Gibran’s most famous and acclaimed work.

[1] Jean Gibran & Kahlil G. Gibran, Kahlil Gibran: Beyond Borders, Foreword by Salma Hayek-Pinault, Northampton, Massachusetts: Interlink Books, 2017, p. 290.