Across Europe, there is a pressing need to define the appropriate stance towards Islam. Is it in harmony with the principles of a democratic constitutional state? Can it coexist with the concept of a religiously neutral state, a norm in many European nations? Can it respect freedom of expression, including the freedom to critique religion (Islam), without seeking to impose Sharia law as an alternative to state law? These questions demand immediate attention.

By Paul Cliteur

In the Netherlands, this discourse gained momentum in 1997 with the release of the book Against the Islamisation of our culture: Dutch identity as the foundation by the late politician Pim Fortuyn, who was tragically assassinated in 2002. The ideologies of parties like

Alternative für Deutschland and the Netherlands' PVV, FVD, and BBB can be traced back to Fortuyn’s 1997 book. Fortuyn eloquently articulated the issue with Islam in his 'laundromat statement', stating, “Judaism and Christianity have largely been through the laundromat of humanism and the Enlightenment. And that is a problem with Islam”.

Fortuyn thus raised a fundamental point about religion. He says, first of all, that the fundamental right of freedom of religion protects religions. But that protection is not unlimited. In other words, religions can also uphold practices that conflict with the requirements of the democratic constitutional state. Religions must be screened for such practices, and undemocratic and unethical views must be changed.

Fortuyn, therefore, presents a standard by which the assessment process of those religions must take place. These are humanism and the Enlightenment. Fortuyn himself was a Catholic. But it was a humanistic Catholicism that he had in mind—an enlightened Catholicism.

It is worth emphasising that Fortuyn’s humanism is the standard for his Catholicism. His Catholicism does not determine what he can adopt from humanism. It is his humanism that determines what he can adopt from Catholicism. Humanism and the Enlightenment form the foundation for religious traditions. Religious traditions do not create the foundation for humanism and the Enlightenment.

Based on these principles, he then presents a comparison of the three major monotheistic religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. He also indicates that the first two have already been cleansed by humanism and the Enlightenment, but that this still needs to happen with Islam.

So much for Fortuyn. What can we add to his statement now, almost thirty years later? What is striking is that we are still dealing with the same issues. And the questions still focus on Islam. The most important question is whether this will still be possible with Islam. Can the laundrette also fulfil its cleansing function in Islam?

The three attitudes towards Islam

Regarding the possibility of this cleansing, three views can be distinguished.

The first is ‘Islamic pessimism’. The Islamic pessimist says: Islam is fundamentally incompatible with the Enlightenment, modernity and secular thinking.

The ‘fundamentalism’ that some warn against is linked to Islam and is ingrained in Islam. The distinction between Islam (the religion) and Islamism (the political-ideological shaping of the religion) is artificial. Islam and Islamism are identical.

This is the position of Islam researcher Hamid Zanaz in L’islamisme vrai visage de l’islam (2012).

The second view is “Islamic optimism”. The Islamic optimist says there is no reason why Islam should not undergo an Enlightenment. After all, Judaism and Christianity did, so why not Islam?

This view is expressed, for example, by Karen Armstrong in her book Islam: A Short History (2002) and more recently by Peter Oborne in The Fate of Abraham: Why the West is wrong about Islam (2022).

According to the Islamic optimist, there is no need for “special integration efforts”. The minor points of friction between Islam and Western-style democracies will disappear on their own. The Islamic optimist bases his view of Islam on liberal variants of Islam or on the behaviour of the ‘ordinary Muslim’, whose views do not differ from those of his non-Muslim compatriots.

Why all this gloomy talk about Islam? In any case, harsh criticism of Islam is considered unnecessary or even counterproductive: it only serves to harden the Muslims in question in their faith. Thus, for example, criticism of Islam creates radicalisation and Islamisation instead of combating them.

The third view is ‘Islamic realism’. The Islamic realist has traits of both the Islamic pessimist and the Islamic optimist. The Islamic realist shares with the Islamic pessimist an awareness of the dark sides of Islam. But he shares with the Islamic optimist the belief that Islam can free itself from these.

However, this requires hard work on integration. And that integration is, in turn, supported by criticism: criticism of Islam. Islam can undergo an Enlightenment, says the Islamic realist, but it has yet to happen. And that will not happen by itself.

It requires criticism, criticism of Islam. Thiemo Sonninger with Einführung in die Islamkritik (2015) or Suzanne Schröter with Politischer Islam: Stresstest für Deutschland (2019) provides that kind of criticism.

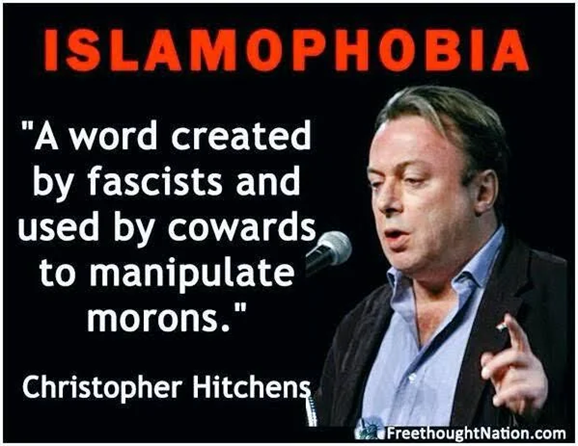

Once again: criticism of Islam should not be discouraged or stigmatised as “hatred of Muslims” (“Islamophobia”), but welcomed. Not all criticism is justified. But the way to determine that is through debate, open discussion, not discouraging discussion. Just as Judaism and Christianity have significantly been “refreshed” by their wash in the laundrette of the Enlightenment and humanism, so too can Islam.

Why Islamic realism is the best attitude

In my opinion, Islamic realism has the best credentials. A characteristic of the Islamic realist is that he argues Islamic optimism is justified, but only on the condition that Islam can also be heavily criticised, as happened with Judaism and Christianity in the early Enlightenment, as with Spinoza. Or in the later Enlightenment by Voltaire and Holbach.

Criticism à la Spinoza, Voltaire and Holbach should also be encouraged regarding Islam. The Islam realist is strongly opposed to discouraging such criticism of Islam as “inciting hatred towards Muslims” and, of course, a fortiori to the criminalisation of criticism of Islam (i.e. the prosecution of criticism of Islam) as advocated by some Islam optimists (“why would you insult believers?”).

Criticism of Islam must therefore be allowed, and indeed made possible, for Islam to develop in the direction of a secular religion. One could also say: this Enlightenment will not happen on its own.

Voltaire and Orwell on criticism

I am in favour of as open a discussion as possible about Islam. Let Islam optimists, Islam pessimists and Islam realists discuss the nature of this religion. This means that I am also in favour of the broadest possible interpretation of freedom of expression, i.e. including “the speech you hate”, according to Anthony Lewis’s well-known characterisation in Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment (2007).

Voltaire, at least in a statement attributed to him by Tallentyre, says: “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it”. This is entirely in line with what George Orwell later wrote: “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear” (George Orwell and Politics, 2020, p. 314).

What is the state of that critical ethos? Not entirely favourable. This was once also the position of the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. But today, a generation seems to be growing up, if it has not already grown up, for whom the words of the ECHR in Handyside v. United Kingdom, 1976, have become incomprehensible:

“Freedom of expression... applies not only to ‘information’ or ‘ideas’ that are favourably received or regarded as inoffensive or as a matter of indifference but also to those that offend, shock or disturb the State or any sector of the population.”

“Offend, shock or disturb”. Nowadays, the reaction is: Would you really do that, 'cause offence”? Why is it necessary to shock? And “disturbing the state or a particular group in society”, why is that necessary? Why not just leave things alone?

Special protection for the religion of the weak

In particular, a religion that, in the words of French thinker Jean Birnbaum, is seen as the religion of the weak (“la religion des faibles”) is shielded from criticism (La religion des faibles: ce que le djihadisme dit de nous, 2018). Criticism of Islam is considered bad taste in progressive left-wing circles.

This creates an alliance between the “left” and “Islam” in the form of what Pierre-André Taguieff has called Islamo-gauchisme. In short, left-wing people want to shield Islam from criticism. Left-wing people are often Islam-optimistic, not Islam-realistic.

Politically speaking, Islamo-gauchisme is a misguided development. It is based on the illusions of Islamic optimism. It tolerates certain unacceptable elements within Islamic culture. But Islamic optimism is not a realistic perspective.

What is needed is a realistic attitude toward Islam, not least for Islam itself. Islam itself has an interest in undergoing a process of purification based on humanism and the Enlightenment. This means that Islam too must adapt to the requirements of the democratic constitutional state.

One could also say that Islam can and should develop into a secular religion, as Judaism and Christianity did in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. Fortuyn’s laundrette has therefore worked. This requires that criticism of Islam be made possible or maintained. The “Islamo-leftism” (“islamogauchisme”) that currently has a considerable part of the Sprachherrschaft class in its grip will have to be abandoned.