The attack in Mannheim, Germany, on Islam critic Michael Stürzenberger is keeping people’s minds busy. Stürzenberger was attacked with a knife on a square in Mannheim by a 25-year-old Afghan immigrant, Sulaiman Ataee. In the process, Stürzenberger was severely injured, but even worse, a police officer who tried to help was fatally wounded. Only Justice Minister Marco Buschmann dared to call it by its name.

By Paul Cliteur

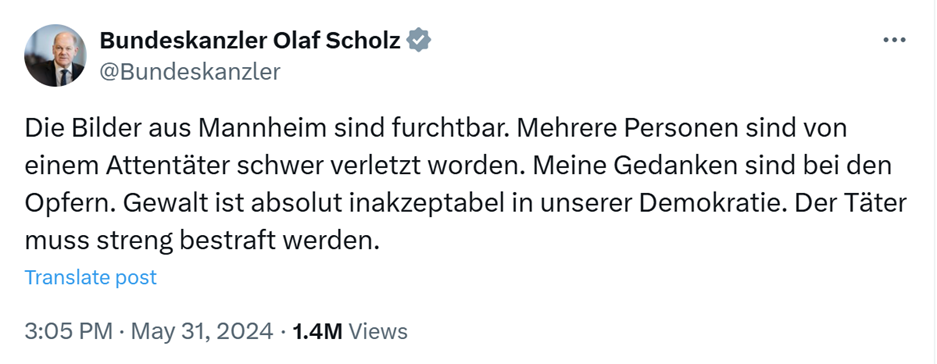

Bundeskanzler Olaf Scholz’s initial comments were vague and not very informative. The Chancellor spoke about how violence is unacceptable in a democracy and that the perpetrator must be punished severely (“Gewalt ist absolut inacceptable in unserer Demokratie. Der Täter muss streng bestraft werden”).

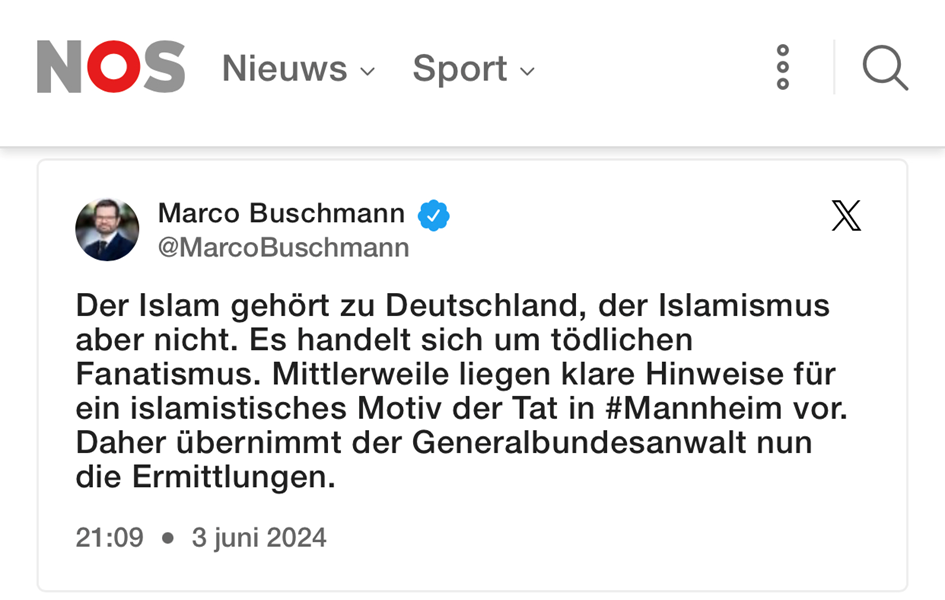

Buschmann had something more interesting: He informed us of the perpetrator’s motive. Buschmann speaks of an “Islamist” motive (“islamistisches Motiv”).

Buschmann thereby distinguishes between Islam and Islamism. Islam, then, is the designation for a religion. Islamism is the designation for a political shaping of a religion. Buschmann welcomes Islam to Germany (“gehört zu Deutschland”).

Islamism, the political design, the ideology that bases itself on Islam, although not identical to it, is not welcome. Furthermore, he says he has clear indications of the perpetrator’s Islamist motives. Ataee’s act of violence can be understood from his Islamist affiliation.

From Dawa to jihad

Buschman thus provides the exact diagnosis of Islamist violence that the Dutch Secret Service (AIVD) presented in 2005, one year after an Islamist attack in The Netherlands, i.e., the murder of filmmaker and Islam critic Theo Van Gogh (1957-2004).

That report is From Dawa to Jihad. The title means: from preaching to violent action. It points to the process of radicalisation in which individuals and communities can find themselves and which can result in a willingness to take violent action.

It is now pertinent that we elaborate on “jihad,” the last part of the AIVD report's title, a little further. The word “jihad” means a holy war. It can refer to an effort that can be seen as a spiritual effort but also to the perpetration of violence and violent action.

The latter is, of course, important here. Sulaiman committed brutal violence (a knife attack) toward Stürzenberger, in all likelihood because of the Islam criticism that Stürzenberger was about to present in that square in Mannheim at a kind of anti-Islamism manifestation.

It was an event organised by Pax Europa, an organisation that seeks to warn against radical Islam, Islamism, or political Islam. “Our criticism is not directed against Muslims, but against political Islam,” a large sign in the square where Stürzenberger had intended to deliver his speech read.

However, according to Islamism or political Islam, it is not permissible to make critical statements about anything that its adherents claim as part of Islamic tradition. A worldview that is at odds with the right to freedom of expression and to demonstrate (here on the square in Mannheim). Radical Islamists also consider violence permissible when demonstrators go against their precepts. In this case, using a knife attack.

Scholz vs. Buschmann

In the comments of Scholz and Buschmann, we see a not insignificant difference in approach. Scholz takes the traditionally politically correct approach: speaking only of “violence,” not of the nature of the violence faced. The Islamist motives of the perpetrator are disregarded. After all, this is “not helpful.” Or “only throws more oil on the fire.” Or “may lead to stereotypes about Muslims in general.”

Politicians guided by this approach are “shocked” at an attack. They declare solidarity with the victims. They call the attack “cowardly.” They call for fraternisation. But they do not say, therefore, “This was an Islamist-inspired attack, and we are going to do everything we can to fight Islamic ideology.

So Buschmann is now breaking with that politically correct mode of expression. He is the minister of justice in Germany. That makes him responsible for security, like our justice ministers in the Netherlands. He names what threatens that security: that is the ideology of Islamism.

It might be enlightening to also spend a single word on the nature of that violent Islamism. It is essential to be clear about the radicality of that kind of thinking. Are we to infer from this attack in Mannheim that Islamism deems it permissible to respond to Islam criticism with a knife attack?

So, brute force to silence the critic? That is indeed the belief of radical Islamism to which Buschmann refers. Buschmann has information that these are the views of Sulaiman Ataee.

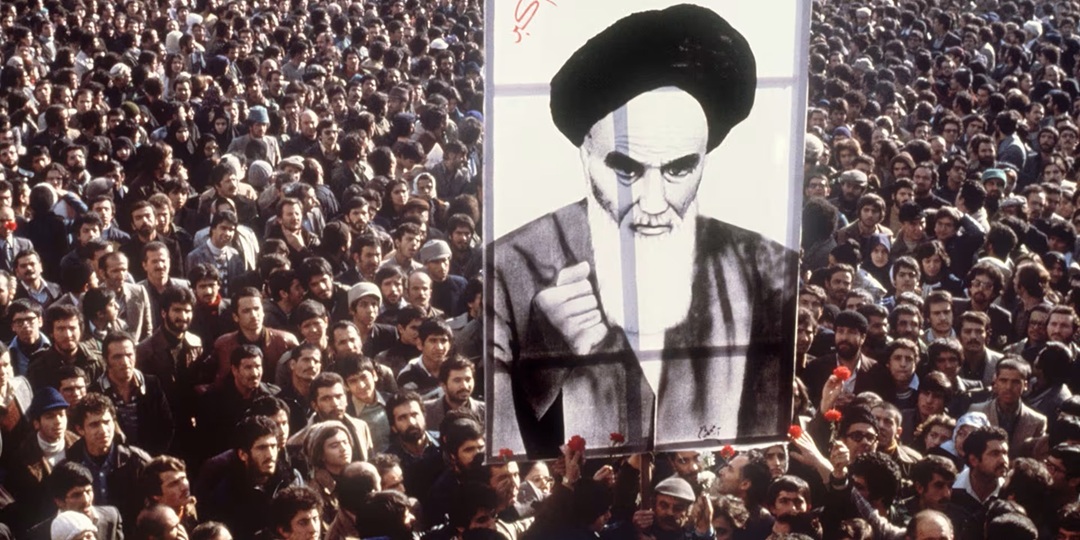

Khomeini’s fatwa is an example of Islamist radicalism

It is hard for Western people to imagine that radical Islamists want to answer criticism of Islam with murder and mayhem. Yet that is the case. The prominent ideologue of these actions is Iranian cleric Ayatollah Khomeini. Khomeini introduced this essentially terrorist strategy in 1989 against Salman Rushdie.

He issued a death sentence (fatwa) on Rushdie because of Rushdie’s Islam criticism (at least, that is how Khomeini perceived it) in the book The Satanic Verses (1988). It is good to read the text of the fatwa carefully to realise how radical that view is.

In this tradition, Sulaiman must have felt legitimised to use violence against Stürzenberger. Even when Sulaiman Ataee has not heard of the fatwa or Khomeini’s figure or teachings, which are not a direct source or influence on him, Khomeini’s ideas are hugely important and influential.

The late ayatollah’s fatwa and the reasoning the former Iranian leader unfolds in this short text are the essence of Islamist ideology. Force is justified to defend Islamic holy views. That is what Buschmann probably means by his reference to a radical Islamist motive.

More will become known about Ataee’s motives in the coming days and weeks. But it seems Buschmann had broken the spell of political correctness.

Of course, many traditional journalistic outlets have pointed out that Stürzenberger is inspired by his activism because of “extreme rightwing views.” Whatever may be true of that claim (not much, by the way; see the text announced on the square in Mannheim), it is irrelevant to understand Ataee’s attack.

A jihadist like Sulaiman probably makes no distinction between left and right. A left-wing writer like Salman Rushdie was stabbed by Hadi Matar, a radical Islamist, in New York State on Aug. 12, 2022. And perhaps Michael Stürzenberger can be identified as a right-wing activist.

Their Islamic conviction is the only thing that motivates Hadi Matar or Sulaiman Ataee. Islamism is the basis for their terrorist acts. Again, Scholz is wrong, and Buschmann is right. This is not simply “force” but terrorist force: the attacker aims to punish the Islam critic. It is precisely that logic that is exposed in Khomeini’s fatwa.

Hadi Matar and Sulaiman Ataee are willing to use terrorist violence if they think the name of God is being slandered by critics à la Stürzenberger or Rushdie. This type of terrorism might be called “Islamist theoterrorism”.