What does late Dutch politician Pim Fortuyn’s criticism of Islam and migration look like? Fortuyn was assassinated by a radical left-wing activist 20 years ago. His spirit still resonates in the Netherlands. He was far ahead of his time, with his ideas on migration and Islam in the West. As illustrated in his ’97 book Against the Islamization of our culture: Dutch identity as foundation (“Tegen de islamisering van onze cultuur: Nederlandse identiteit als fundament”).

By Paul Cliteur

In it, Fortuyn writes that the Netherlands is characterised by cultural relativism. People are no longer interested in their heritage and its inheritors. One knows its patriotic history poorly; even the constitutional law system, with democracy as its foundation, often remains underexposed. However, some cultures in this world have a strong identity, and those cultures exclude other cultures.

This is how Fortuyn comes to Islam. He writes: “In our so-called multicultural society, (fundamentalist) Islamic culture and traditional Dutch culture come into daily contact. Hereby, due to our disinterest in our own identity and the essence of our society, our original culture threatens to fall completely. We must do all we can to prevent this” (p. 201).

Bolkestein as forerunner of Fortuyn

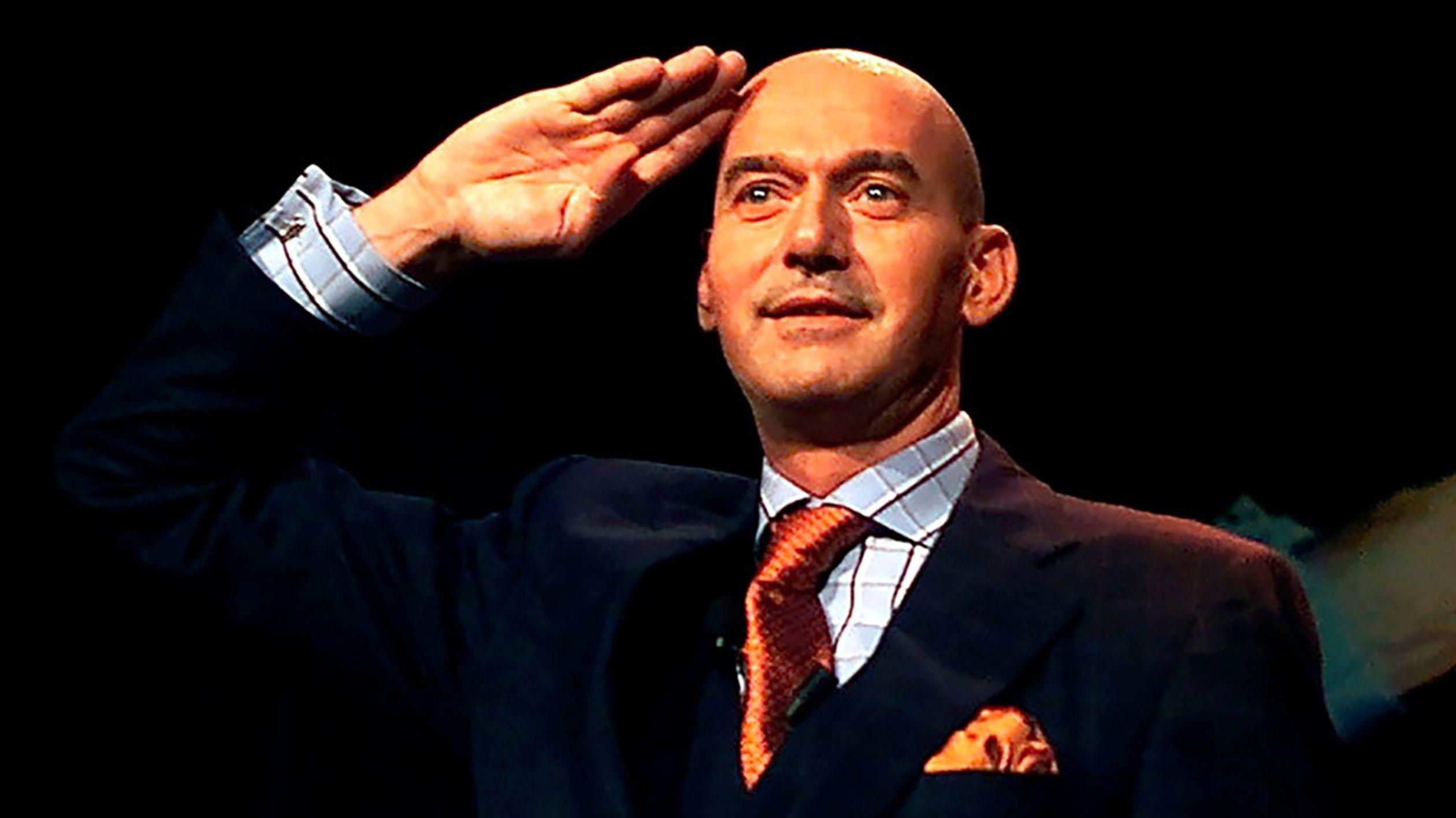

This 1997 critique of Islam is the successor to the critique of Islam in the late Frits Bolkestein’s famous 1991 essay. Bolkestein (1933-2025) was a well-known Dutch liberal politician and energy executive who served as Leader of the People's Party for Freedom and Democracy from 1990 to 1998 and European Commissioner for Internal Market from 1999 until 2004.

This essay is the second manifestation of Islamic criticism in Dutch politics, and it sent a shockwave through the country after its publication. On September 12, 1991, Bolkestein wrote an article in a left-wing newspaper, De Volkskrant, putting political Islam criticism on the map for the first time in Dutch politics.

The article was titled “The integration of minorities must be tackled with guts.”

There, Bolkestein points to four universal values that should play a central role in integrating minorities: “the separation of church and state, freedom of speech, tolerance, and non-discrimination.”

According to liberals, these are universal principles. According to Bolkestein, this would have become commonplace in Judaism and Christianity, but not Islam. Fortuyn endorses this, but he elaborates on this in his book Against the Islamization of our culture.

With Bolkestein, nothing happened within the VVD

By now, it had become clear within the VVD that Bolkestein’s criticism of Islam would not be followed. However, much of what Bolkestein expounded in his 1991 essay caught on outside the VVD, such as with the then-public intellectual Fortuyn.

Fortuyn would later attempt to found a political party, but in 1997, he had not yet gotten around to it. He was busy developing a political worldview, and Islamic criticism played an important role.

Let’s review his argument. Fortuyn argued that a “political and social debate” about the values and norms on which Dutch multicultural society should be based is necessary. He stated, “Essential will be a good understanding of the differences between (fundamentalist) Islam and the traditional Judeo-Christian humanist culture” (p. 201).

This quote again reveals several distinctive aspects of Fortuyn’s worldview. First, he holds the Judeo-Christian humanistic culture as a standard. That is a fusion of three different currents: Judaism, Christianity, and humanism. Fortuyn buries an old battle between Judaism and Christianity. Judaism and Christianity, despite their differences, are one culture. But also striking is that he makes humanism part of that, again harmoniously.

Humanism as part of Western culture

Is that special? The answer is “yes”. Humanism is generally classified as non-religious. Fortuyn does not heavily emphasise this difference between the religions of Judaism and Christianity, on the one hand, and the non-religious worldview of humanism, on the other hand.

However, it is undoubtedly as crucial as Fortuyn's notes on the similarities between Judaism, Christianity, and humanism, where Fortuyn draws the line with Islam.

For Fortuyn, our culture is not a Judeo-Christian-humanist-Islamic culture. Islam stands apart and is considered “fundamentalist” by him. Just as with Bolkestein. Where does that fundamentalism show up? Fortuyn says that the conflict with fundamentalist Islam centres on three areas: “the separation of church and state, intercourse between the sexes and the relationship between children and adults” (p. 202).

Compared to the four areas where Bolkestein noted tension with Islam (“the separation of church and state, freedom of speech, tolerance and non-discrimination”), the separation of church and state is the same. Implicit in Fortuyn’s point about “intercourse between sexes” is also Bolkestein’s “non-discrimination,” after all, Bolkestein was also referring to women’s discrimination within Islam.

Cultural relativism

Bolkestein and Fortuyn have identical ideas about cultural relativism: It should be rejected. Cultural relativism is the idea that there are no universal values and norms. All values and standards are culture-specific, and one culture cannot measure the values of another.

Adopting cultural relativism would have far-reaching consequences for integration policies toward newcomers to Dutch society. Integration policy becomes impossible with cultural relativism. After all, how could you expect people from a non-Western culture to adopt Western culture's values? That would be an impossible demand and, therefore, should not be demanded.

However, Bolkestein's four fundamental values present a demand that may indeed be made of newcomers. Fortuyn does the same with his three fundamental values. And so those “newcomers” include Islamic immigrants. Islamic immigrants should adapt to the Judeo-Christian-humanist culture in terms of those fundamental values.

Left and right regarding cultural relativism

Here lies a difference between “left” and “right.” The right rejects cultural relativism. The left embraces cultural relativism. The left says that people can live according to their values and norms. Integration policy is, therefore, illegitimate according to the left. Fortuyn makes a strong point about his criticism of cultural relativism.

He writes: “We now get away with a kind of cultural relativism, in which we delude ourselves that it is no longer necessary for us as a people to want something and be something, in which we leave our history behind us and no longer need to know it, let alone live it” (p. 203).

Fortuyn, however, believes that a people without a consciously lived identity eventually becomes a collection of people who, although living within one state context, are no longer each other’s guardians. You are no longer a “society,” but a loose association of individuals, a powerless people without common ideals. “With such people, things do not end well in the end” (p. 204).

Fundamentalism

Now, according to Fortuyn, Islam is “fundamentalist” or predominantly fundamentalist. What does Fortuyn understand by “fundamentalism”? He defines the following: “Fundamentalism is a political attitude based on a view of society or a religious view, in which the religious view or view of society is taken absolutely and functions as determining the political attitude” (p. 219).

In other words, fundamentalists are absolutists. The values and norms that derive from their view of society or their religious view are also fully normative for those who do not hold the relevant view of society or religious view” (p. 219). Views other than those of the fundamentalist must be eliminated, according to the fundamentalist’s aspiration. The spiritual view of the fundamentalist is thus totalitarian (p. 220). This means that the fundamentalist view extends to all areas of life, both public and private.

As examples of a religious fundamentalist worldview, he points to Khomeini’s fatwa on Rushdie or Calvin’s view. He also names Jewish fundamentalism and sees it at work in the assassination of Prime Minister Rabin (p. 220). Examples of Catholic fundamentalism that Fortuyn does not give.

Fortuyn’s reaction to Bolkestein

Of course, Fortuyn is aware that six years earlier, Bolkestein had written an article about Islam, the integration of minorities, and the foundations of Western culture. Fortuyn reflects on the relationship between his perspective and Bolkestein’s. He writes, “No politician or party dares to openly demand respect from the foreigners to be integrated into the Dutch language and culture” (p. 226).

Here we see the beginning of his party program emerging: he, Fortuyn, will. His party will dare to demand respect for the Dutch language and culture among newcomers. But what about Bolkestein, didn’t he do the same? Fortuyn answers: “The VVD politician Bolkestein has made an attempt, but only expresses himself in very defensive terms and is constantly on the defensive in this debate” (p. 226).

This has been correctly observed. Bolkestein had indeed only “made a single attempt,” but he had quickly stopped beating this drum when he saw how much resistance it generated. Fortuyn now seems intent on proposing a more courageous integration policy, with a somewhat more coercive tone.

Why did Bolkestein button down with his criticism of Islam? Was he impressed by the many criticisms he received? So did he succumb to pressure from the cultural-administrative-intellectual establishment? Or was he also fearful of violent consequences that seemed attached to Islamic criticism?

We must remember: Bolkestein wrote about two years after the Rushdie fatwa. We had not yet had the murder of Theo van Gogh (2004), not yet Danish cartoons (2005), French cartoons (2015), not yet the murder of Samuel Paty (2020) or Salwan Momika (2025).

Nevertheless, Bolkestein was an internationally oriented thinker. He must have realised the consequences of the Rushdie Affair. This is partly why he realised the need to integrate minorities into the four fundamental values for a liberal democratic culture, which he formulated in 1991.

Fortuyn charges Bolkestein with having been far too timid. “Not his fellow politicians who refuse to define Dutch identity must answer for it, but he who makes an extremely timid attempt in very defensive terms must answer for it” (p. 226). This is the declaration of war by the leader of a new political party against Bolkestein’s VVD: too timid, too defensive.

The difference in attitude between Bolkestein and Fortuyn was manifest. Bolkestein had been barked back into his pen after 1991 by allegations of racism, but Fortuyn outright declares war on the leftist “anti-racists.” “Putting the importance of the Dutch language, culture, and identity concerning Dutch people of foreign origin immediately draws into the framework of possible racism.

It produces Pavlov reactions without fail” (p. 226). Fortuyn also denounces the “prosecution policy on racist expressions” (p. 226). He notes that only white Dutch people are persecuted: “fellow colored people of foreign descent are spared that” (p. 226).

Fortuyn settles a new taboo: the Dutch Public Prosecution Service's prosecution policy, which is rarely criticised.

Cultural relativism is not the answer

How do we get out of this impasse? Let’s start with what Fortuyn says is not the answer. Not the answer is cultural relativism. Fortuyn writes that cultural relativism weakens self-identity and dismantles society’s core values.

Cultural relativism also has no “rebuttal” to “people and cultures that do not care about cultural relativism and often contrast their own identity and culture with it in an absolute sense” (p. 227). In other words, cultural relativism cannot respond to the fundamentalism of Islam. But what then?

The answer to that question was given by Fortuyn in April 2002, just one month before his death (May 6, 2002), in a television program in which he was questioned about his criticism of Islam.

This criticism of Islam came up in the context of a reflection on special education, which, as is well known, allows schools to be founded on a religious basis, including an Islamic basis. Is Fortuyn in favour of abolishing special education?

He answers this question by not favouring abolition, because not all religions are equal. “Judaism and Christianity have largely gone through the laundromat of humanism and the Enlightenment. And that’s a problem with Islam”.

Here lies the key to solving the minorities’ problem as Fortuyn envisioned it in 1997, a problem Bolkestein described in more or less the same terms in 1991. How to stand up to a fundamentalist Islam that, through special education, teaches norms and values that are at odds with the Dutch core values, which Bolkestein had formulated in his four instances in 1991 and Fortuyn with his three values in 1997?

In Fortuyn’s “laundromat statement” lies the answer to that question. But then the laundromat statement must be interpreted correctly, and neither Bolkestein nor Fortuyn has in fact done that themselves. They have given some hints of an answer, but not a complete answer. I first indicate what an incorrect answer to the laundromat statement looks like, then what a correct answer looks like.

The misinterpretation of the laundry ruling

The misinterpretation of the laundromat statement is that Judaism and Christianity are, in fact, superior religions to Islam. What is left in terms of integration policy for Muslims is to become Christian or Jewish. Islam should be dropped.

After all, Islam is essentially fundamentalist and forever incompatible with Judaism and Christianity, which in turn are the basis for Dutch values and norms and Western values and norms in general.

It is this misinterpretation of the launderette statement that makes it impossible for second, third, and fourth generation Muslim immigrants to go along with Fortuyn or with Bolkestein.

They feel they are thereby being lectured by the representatives of this progressive integration policy: “You will integrate. And that is only possible if you deny a part of yourself. You must declare that you distance yourself from your fundamentalist religion.”

Bolkestein and Fortuyn never reflected deeply on this point. Bolkestein contented himself with addressing a problem and left it to others to solve it. Fortuyn wrestled with the issue further* but did not get much further than presenting the laundromat assignment a month before his death.

For Muslims, the laundry assignment always remained unacceptable because they saw that it was formulated only concerning their religion. Did this not discriminate against them as Muslims?

The correct interpretation of the laundry statement

So, Fortuyn did not present the correct interpretation of the laundromat statement. Fortuyn was Catholic, and that also colored the way he viewed the world. His examples of intolerant religious elements were drawn from Islam and Protestant Christianity (Calvin).

He conveniently forgot that Catholicism also has a long history of intolerance. What he also overlooked were the implications of the laundromat ruling. What are those implications?

To realise that, we need to recognise that Fortuyn said Judaism and Christianity had gone through humanism and enlightenment and thus “washed clean,” a process Islam would still have to go through. But that means we need to make a distinction between wax and wash.

So, too, Judaism and Christianity were (and to some extent still are) laundry. Humanism and enlightenment wash laundry. So,--* the standard for integration policy is set by humanism and enlightenment, not by Judaism and Christianity.

This essentially solves the problems for contemporary Muslims regarding the perspective of Fortuyn and Bolkestein. Bolkestein’s four values and Fortuyn’s three values are universal, transcending religion. One can also say that fundamentalism, as the denial of Bolkestein’s four values and Fortuyn’s three values, is a problem for all religions. Caroline Fourest and Fiametta Venner describe Catholic fundamentalism in their book Les Nouveaux Soldats du Vatican (2008).

The solution is enlightened Catholicism, which can exist, as proven by the development of the Catholic Church. Pim Fortuyn is an example of enlightened Catholicism.

This standard of humanism and enlightenment also applies to Islam. The question then naturally arises: is an enlightened humanist Islam possible? Is Hamid Zanaz right that Islamism is the true face of Islam, in L’Islamisme vrai visage de l’Islam (2012), or is it possible, as Malek Chebel suggests, to develop a Manifeste pour un Islam des Lumières (2004)?

The answer to this question is decisive for policy development. If humanistically enlightened Islam is possible, integration policy can be based on it. If a humanistically enlightened Islam is impossible, the policy to be followed would have a clear consequence: an absolute ban on immigration for people originating from Islamic countries.