Emotions often take a back seat to strategies and policies in the intricate tapestry of modern geopolitics. Yet, collective emotions like anxiety shape political decisions and redefine global alignments, particularly in regions fraught with ideological, ethnic, and religious complexities. Nowhere is this dynamic more evident than in Syria, a nation whose internal fractures and external entanglements illustrate how collective anxiety can influence geopolitics.

By Ahmad Ghosn

In psychoanalysis, especially Freudian psychoanalysis, anxiety centres around the issues of loss, castration, and exclusion. This is precisely the diagnosis of what is happening with minorities in Syria. They are anxious about their existence and recognition and about repeating the experience of “the necessity of being a Baathist to enter public administrations.”

The anxiety of minorities today extends beyond political castration. The actual anxiety is ideological castration—a fear that the “Brotherhoodisation” of the state’s institutions will result in the annihilation of minority ideologies.

For 54 years, the regime maintained its grip on power by protecting this “ideological privacy” under the guise of tyranny. Syria's geopolitics has transformed from “the geography of power” into “the geography of anxiety”. This anxiety has many consequences, and there are many competing views as to which one is the worst.

The Roots of Anxiety in Syria

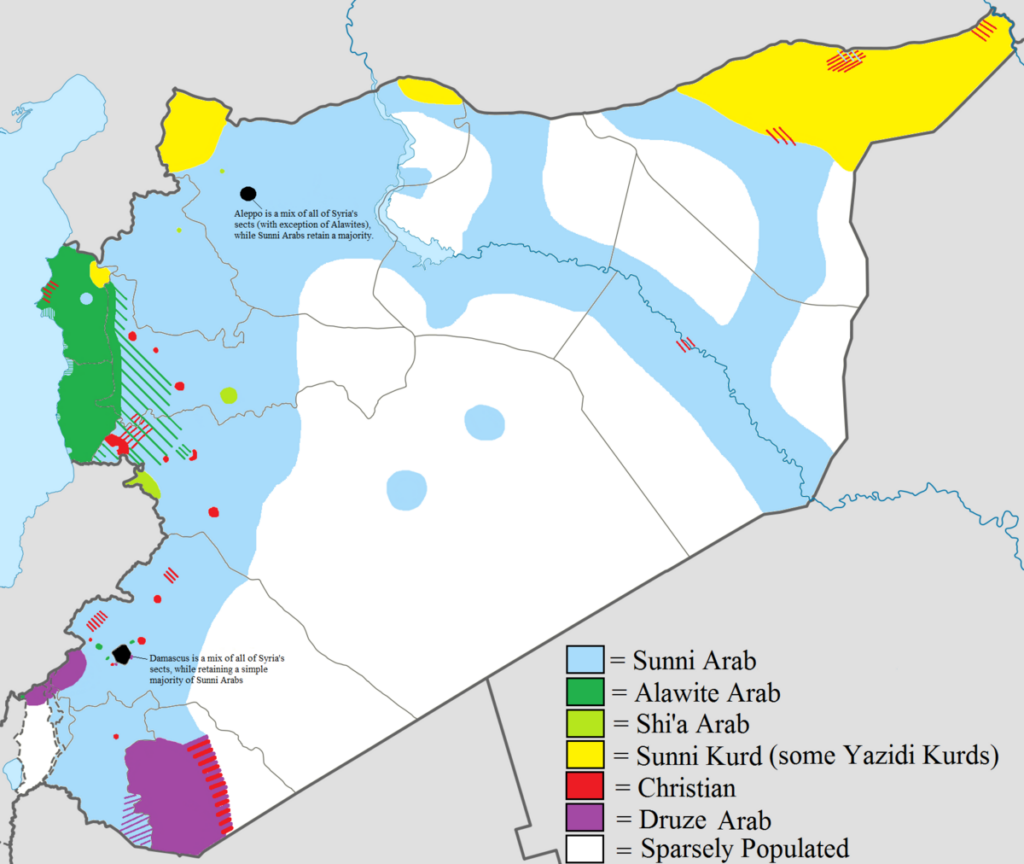

Syria’s diversity has long been both a strength and a source of tension. The country’s majority Sunni population harbours deep-seated fears about losing power after ascending it, while minorities such as the Druze, Kurds, Christians, and Alawites fear marginalisation or outright persecution.

These anxieties are not new; they have historical roots in the colonial era and have been exacerbated by decades of authoritarian rule and systemic inequality that often seemed sectarian but was, in reality, a divide between those close to the Assad regime and ordinary citizens, regardless of religion.

The 2011 uprising, initially fuelled by demands for reform and justice, quickly evolved into a civil war that laid bare these underlying fears. For the Sunni majority, the prospect of leading a post-Assad Syria brings its anxieties.

Many worry about the spectre of Islamist rule, specifically the influence of groups like the Muslim Brotherhood and how it might shape a future state. Many secular Sunnis share these concerns. Conversely, minorities like the Druze, Christians, and Alawites fear being sidelined in a Sunni-dominated political landscape.

The Kurds, who have carved out autonomous zones in northern Syria, are wary of Turkish aggression and a lack of long-term international support. Meanwhile, the Alawite community, long exploited by the Assad regime, faces an existential crisis about its survival after the fall of the regime.

The Suspicious Legitimacy of the Syrian Transitional Government

Syria has shifted from a one-party system to a one-sect system. Today, the Syrian transitional government comprises 22 Sunni ministers, nominated by the HTS, not considering any other opposition groups or sect, with no representation from Kurds, Alawites, Druze, Shiites, or Christians, contrary to what is specified in 2254 United Nations Security Council Resolution.

This lack of inclusivity is one of the primary drivers of anxiety across the country. While crucial in a transitional period, Revolutionary legitimacy does not grant carte blanche to create an exclusionary regime or engage in authoritarian practices.

Revolutionary legitimacy is not a license for dictatorship or exclusion. It does not justify suspending accountability or disregarding ordinary laws until judicial committees - possibly international - are formed to ensure fair processes. Many see the detention of thousands of soldiers in undeclared prisons and the restructuring of public jobs to remove technocrats who did not participate in combat operations as attempts to consolidate power. These actions undermine the principles of fairness and transparency; some people think it would be a plan to gain the upcoming election.

The unilaterally formed Syrian army and internal security forces, created by one sect without constitutional guarantees, are perceived as blatant efforts to consolidate power. This further fuels anxiety among Syria’s diverse communities. International bodies and countries such as the United States, the European Union, and Turkey have highlighted that the current government is not an accurate representation of the Syrian people.

A joint statement published on the US Department of State website on December 14, 2024, affirms the need for a government that represents all Syrians, respects women and minorities, and adheres to the principles of Resolution 2254. This resolution calls for a comprehensive and inclusive transitional government—a goal the current regime has yet to achieve.

Anxiety's Strategic Effects

This pervasive anxiety is not confined within Syria’s borders; it radiates outward, influencing the strategies of regional and global powers. For instance, the recent appeal by the Druze village of Hader to join Israel exemplifies the geopolitical uncertainty stemming from anxiety.

A Druze sheikh declared: “Joining Israel is much less than the evil that will befall us if the militants reach us.” Their calls for protection could lead Israel to deepen its involvement in Syria, driven by "humanitarian" arguments and strategic interests in expanding its regional influence.

Likewise, France, with its historical ties to Syria’s Christian population, could seek to reestablish its presence under the pretext of protecting minorities. The United States, with its vested interest in Kurdish territories, might continue to support the Kurds militarily to safeguard oil and gas fields while countering Russian and Iranian influence.

Conversely, Russian support could be directed to the Alawite coast to secure its strategic access to the Mediterranean. Through militarisation, support for separatist projects, or political manoeuvres, these interventions feed into the cycle of anxiety, creating a geopolitical chessboard where the stakes are both human and territorial.

Lebanon: A Mirror and a Warning

One needs to look no further than Syria's neighbour, Lebanon, to understand the potential trajectory of Syria's divisions. Often described as “A House of Many Mansions,” Dr. Kamal Salibi’s book title succinctly captures this paradox. Lebanon’s model of coexistence is a fragile balance of sectarian power-sharing.

While it has allowed the country to avoid outright disintegration, it has also entrenched divisions, fostering a politics of patronage and perpetuating cycles of instability.

In Lebanon, coexistence often means living side by side without genuine integration—a dynamic that could take root in Syria. As communities carve out autonomous zones, the potential for cooperation diminishes, replaced by a wary detente that stifles national unity.

Reflecting on the regime's strategic mistakes in 2011, one cannot help but wonder how different Syria’s trajectory might have been had it chosen reform over repression. Granting ministerial participation to opposition figures, addressing grievances, and activating political participation would have tempered the uprising and perhaps prevented the descent into chaos. Today, what is required is not to repeat the 2011 tragedy.

The Sunni community in Syria should not be anxious, especially those currently in power. Anxiety is not a majority’s trend; it is a minority’s habit. Any clash between the Sunni majority’s anxiety and the minorities' anxiety will be resounding.

The results are precise: If the ruling clique can embrace minorities and establish national principles, Syria could emulate the Turkish model—a state that is sectarian in form but civil in content. However, if anxieties are not addressed and fair, satisfactory policies are not implemented for all, Syria risks “Lebanonization.” It will become a state that is civil in form but sectarian in content.

“The Geopolitics of Anxiety” highlights a vital lesson for Syria and the Middle East: Emotions are as potent as armies in shaping political landscapes. Anxiety and mistrust can fracture nations, but organisation, inclusivity, and peaceful transition can pave the way for unity. As Syria’s stakeholders navigate its uncertain future, they must confront not only the physical and political debris of war but also the emotional scars that linger. The region can hope to transcend the geopolitics of anxiety by addressing these concerns.

The scenario of dividing Syria is impractical due to the danger it could cause to Turkey, Iraq, Jordan and Lebanon and the spread of this division contagion. But if things get out of hand, all possibilities become open.