We always know what our friends should do. We are exceptional at giving advice. It’s measured. It’s empathetic. It’s wise.

“Quit the job, end the relationship, take the risk, move on”. Somehow, the solution shines like a neon sign when it's someone else's life. We offer our opinions with conviction, wrap them in empathy, and press them into the hands of the people we care about.

But applying that same wisdom inward? That’s where the friction lies. When the problem is our own, everything gets murky.

What felt obvious in someone else’s story becomes tangled in our own. Doubt creeps in. The stakes feel heavier. And the advice we once gave so confidently starts to sound simplistic. It is too easy for something as complex as this situation, this context, this version of ourselves.

Sure, we might be great at giving advice, but seeing things clearly is a whole different game when it comes to ourselves. Self-perspective, the ability to look at our own lives without all the emotional clutter, is honestly one of the hardest things to get right.

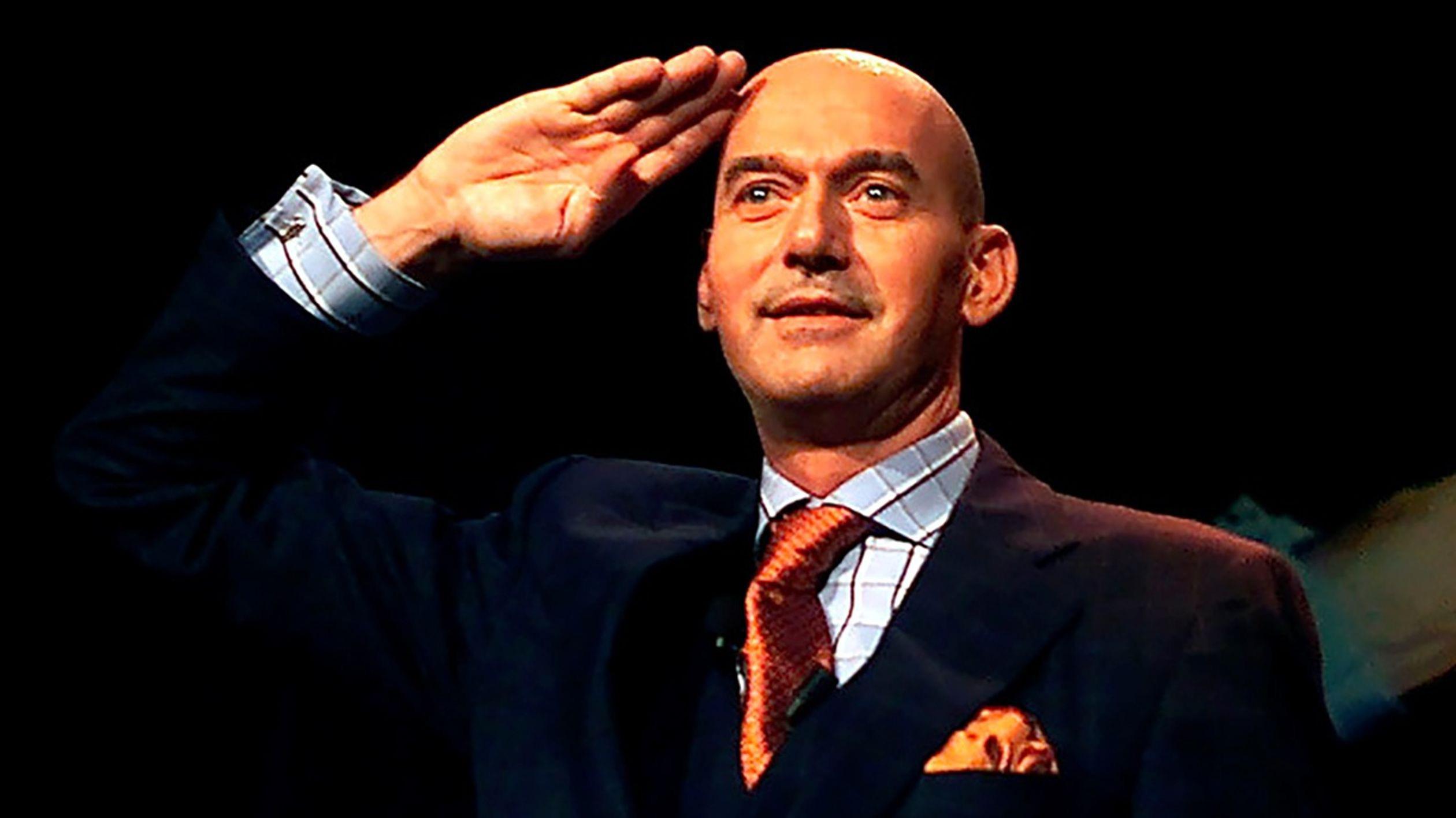

The idea is that we reason more wisely about other people’s problems than our own. Even King Solomon, revered for his wisdom, especially in governance and conflict, struggled to apply it in his personal life, which was marked by poor decisions, particularly in his relationships and leadership choices. And really, who among us hasn’t played both roles: the all-knowing sage in someone else’s story and the confused wanderer in our own?

When advising someone else, we benefit from psychological distance, a gap between us and the problem that allows for clearer reasoning, less emotional interference, and more cognitive flexibility. Our ego isn’t entangled. Our fears aren’t magnified. And our narrative - the regrets, defense mechanisms, and unresolved guilt - doesn’t cloud the lens.

When the situation turns inward, that clarity collapses. The same mind that solves others’ puzzles with ease becomes hijacked by cognitive biases, particularly self-serving bias, confirmation bias, and rumination loops. We don’t just analyze; we spiral.

The mind attaches to identity, past failures, and anticipated judgment. We get stuck in the darkest corners of the psyche, unable to zoom out and see the board clearly.

It’s not just psychological; it’s cultural. We live in an age obsessed with self-improvement yet allergic to vulnerability. Social media has turned self-help into a spectacle: everyone has a morning routine, a framework, a “healing journey.” Online, we’re all mentors. Offline, many of us are quietly struggling.

Advice-giving has become performative, a mask of authority worn over layers of uncertainty. Behind every confident caption, there often lies a person just as lost as the one they’re trying to save.