By Gouthama Siddarthan

When my book, ‘I travagli politici del viaggio nel tempo' - (Translation by Davite Mana), was published in Italian, it was Domenico Attianese, who for the first time introduced it. It was thanks to his introduction that my book hogged a widespread attention. Also, Vincenzo Barone Lumaga’s a critical article about the book was widely acclaimed among the Italian readers. Consequently, critics Fabrizio Borgio, Massimo Luciani added fuel to the rage.

Meanwhile, my email inbox was teeming with a spate of letters from Italian, among which the most important is Roberto Paura’s. Praising the perspective put forward in my book, he asked me why I had prematurely published the book and said how he wished I had got it published in any of the European English magazines first so that the book would have had a global reach. He also suggested that I bring out a new version incorporating the Italian translations of Ray Bradbury and Alfred Bester and publish it through a Italian publishing house. My heartfelt thanks to him for his kind opinions.

I may seem to be beating about the bush; but it’s not without reason. For, my original intention is to speak elaborately about a letter that I had got recently.

Yes! It was a peculiar mail in that it had no trace of the sender. Wondering if such anonymous mails were possible, I went through it.

Did I say I went through it? Nay, I didn’t, for it was written in a weird language that defied my intellect. Anxiety and agility spurring me on, I turned to Google which, in turn, stood dumbfounded.

Full of exotic and outlandish symbols, the mail set me whirling in the vortex of confusion.

Is it the Klingons language? We had better consult Klingonist Lawrence M.Schoen. (It is highly boring that he conveys birthday greetings to Facebook friends identically in the Klingonese. He must be told that it is a challenge for a seasoned artiste to convey greetings in a language with an elegance and charm that characterize symbols operating in the boundless linguistic possibilities).

Coming back to the anonymous mail, I examined it deeply. As I trod the terrain of symbols swirling and zigzagging like a labyrinth, it felt like a fire that touched every pore of my physique with its never-ending flames and endless doors kept on opening up to the mysterious interiors.

*************

In 1990s, after reading ‘If on a winter’s night a traveller’, I turned mad about Italo Calvino and the craze gripping me frenetically, I went in search of his writings and read whatever I lay my hands on. The madness was so mighty that I went to the extent of learning the novel by heart. At one point of time, I turned crazy to the point of wandering about in our native streets in search of a woman literary buff a la Ludmilla.

It is an in-thing that our Tamil literary conclaves witness no more than 7 to 12 participants, all men. The literary section of simple modern Tamil book houses is always deserted, the stalls selling third-rate books teeming with crowds. But I personally want Ludmillas, not Manroes.

Though my mind became vexed, it had not given up its search. On a day of an intense search, when I was leafing through pages of the book, ‘Under the Jaguar Sun’ in an English book stall, I held my breath: O me! Over there facing me was standing Ludmilla, ‘If on a winter’s night a traveller’ in her hands. Yes. The same Ludmilla I have for ages been craving for.

For a moment, all movements in me came to a standstill, her eyes and mine meeting at a horizontal point; then the famous poetic line in our Tamil epic ‘Kambaramayanam’ came back alive: “Our Lord glanced and so did she.” 1.

That place was ablaze with rays from Jaguar Sun.

A sweet smile flitting across lips, she moved to the next stall, my blood flowing faster in veins. I was following her, quite anxious about how to strike a conversation. As she turned and threw a glance at me, her eyelids fluttered like the wings of a butterfly. A swirling strand was descending from her elegant parting of hair and hanging from her left temple, quickening the 360-degree revolution of the earth.

As we were having Coffee at a stall outside after introductory remarks, I happened to know she belonged to Italy, as I had expected. She had come to visit sculptures in Tamil Nadu. She did not know Tamil, nor did I know Italian. When I was stammering in my poor English, she could guess whatever I tried to communicate; at that moment, how I hated Tamil Nadu’s language-oriented politics which had denied me, like so many, the opportunity to learn other languages than the mother tongue.

She told something like her name; but paying no heed to it, I asked her if I could call her Ludmilla. After moments of keenly staring at me, she smilingly nodded as if in agreement.

She said that being a student of linguistics, she was researching the dying languages. Was it not enough for me to strike a chord with her? So, I said, “I know certain features of such languages,” Her almond-hued eyes merged with mine.

At that moment, I began playing my guitar on a cement bench in a corner of the pasture opposite the Rome’s Colosseum. Thunderstruck notes kept tumbling out of the strings that vibrated more intensely as the pitch was slowly rising, as if in resonance with the sounds of thunder. As I played the most romantic poem from ‘Kurunthogai’, the work of our glorious Tamil Sangam literature2, “Whoever are my mom and yours,” the music filled the antediluvian wall of the Colosseum. My fingers flitting across the G chord, the key of benediction in Baroque music, the notes flooded the landscape and Hey Presto! Bursting through the swelling notes was Ludmilla. She took my finger dripping with blood, tired as it was from playing guitar, and kissed it with her lovely lips: Then I said, “I love you, Ludmilla.”

Then, a sudden horn from the electric train pulled me back to Tamil Nadu.

Casting aside her empty coffee cup, she rose to depart, as I grew tense.

“Listen, why don’t we exchange our phone numbers?” I said. (This is what you were aiming at. O, Reader, moving around her like a rattlesnake!” so says Calvino).

“How can I meet you again? Could I get your phone number? I can be of god help for your linguistic research,” I said.

“As I have come down here just as a tourist, I have no personal contact number. Please, give me yours. I will call you up,” she said.

After getting my number, she waved to an autorickshaw passing by, breezed into it and disappeared.

Back home, I couldn’t compose myself, fidgeting as I was, waiting for her call. Next day, she called me to say we could meet at the Egmore museum, putting me on the cloud nine.

Now, another kind of anxiety gripped my head. I remembered she said something about her linguistic research. So, to help her and more importantly, to impress her amazingly and thereby sustain her relationship, I must collect and give her some data vital to her work. That should be something she had unheard of.

As I was pondering over the question, the story, ‘Confluence’, by Brian W. Aldiss flashed across my mind.

The story, having shed the usual story-telling narrative form, looks like a dictionary for a new language. That is to say, Aldiss puts forward a page from the dictionary of the language belonging to a planet. That page has visions of the life on the exotic planet. It is a text that amplifies the art, culture, politics and society, the warmth and human existence through the words in the lexicon. A wonderful text it is!

Such an amazing thing should be discovered.

In an instant, a musical note flashed in my head teeming with streams of thoughts.

*************************

It is the musical note of Muthu, my childhood friend, who used to carry dirty clothes through a donkey.

Yes! In our country, there is a caste called ‘Vannar’, nowadays called washerman, whose prime duty it is to wash the dirty clothes. As part of our sordid age-old Varnashram (classification of the society into four major categories, based on occupation), the Vannars have been assigned the work of washing dirty clothes of the people, who are above them in rank, occupation, wealth and status. It has been practised and is still being practised in our society, giving birth to countless castes and thereby, having built-up a rigid caste system that has for ages oppressed the downtrodden.

In villages, the ‘Vannar’ community is even now subjected to the cruel and harrowing work of washing dirty clothes for a pittance.

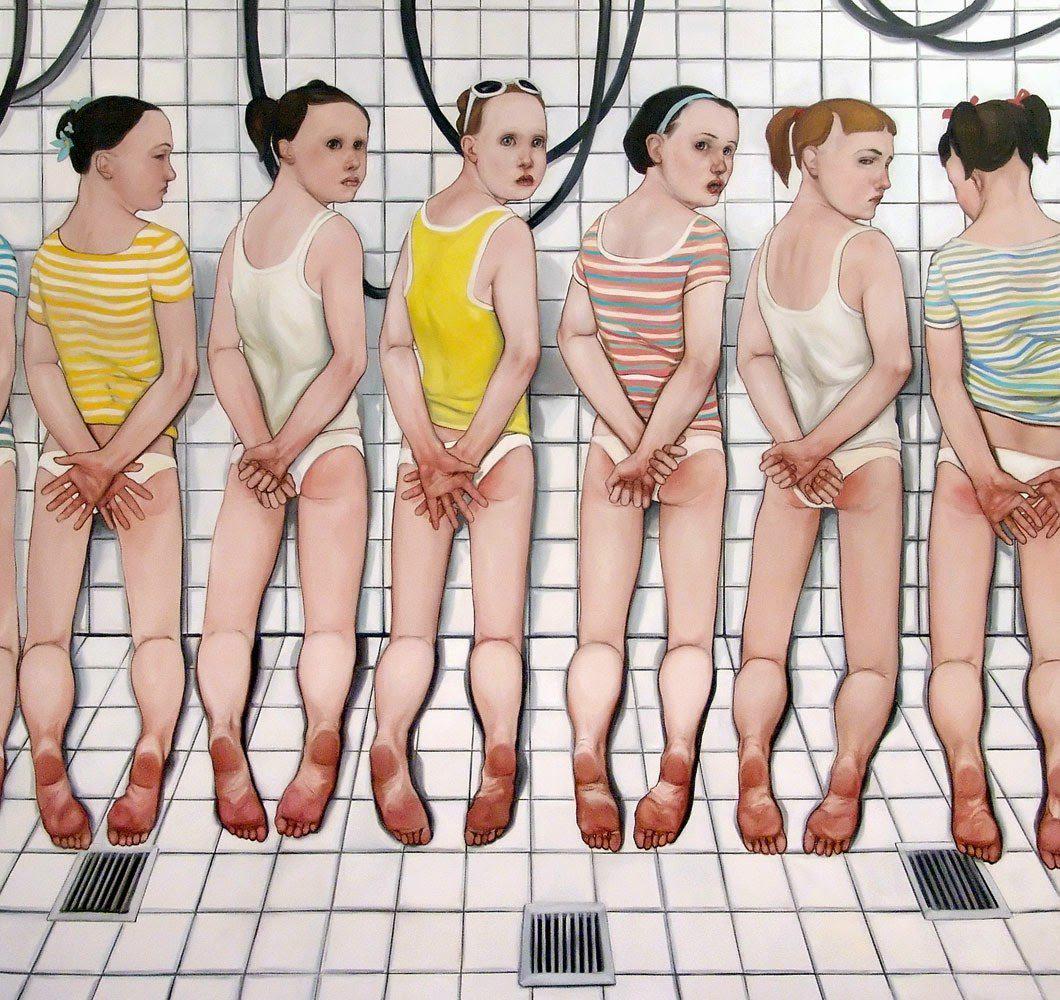

Among the people of that community, there is a rare linguistic perspective. While collecting clothes from various people, they inscribe small symbols inside the clothes for the purpose of identification. These marks are called ‘vannaan kuris’ (washerman’s sympols). Among these identification marks, there lies hidden an over 2,000-year-old symbolism, as also a new linguistic outlook. The symbols’ quality and the background of their formation merit a deep research.

From my childhood, the ‘hide-and-seek’ game (in Tamil it is called ‘kannaampoochi’) has been favourite with me. In the prime of my youth, my game companion was Muthu belonging to the Vannar community.

As I spread my hands in the ‘kannaampoochi’, Muthu would inscribe on them weird marks, singing a folk song:

“Kannaam Kannaampoochi

In the lines hides the hen

In the book hide the seven 3

Run out in search of it

And catch hold of the hidden”

As my friend was singing this song, all children would disperse and hide themselves in whatever places they would choose. After done with singing, he would set me upon the trail, his marks on my hands serving as clues.

On a day of the game, I was on the trail of my companions, who were hiding at different places and got weary of the search. Then I happened on a small, semicircular lane, after tip-toeing inside several cavities. The lane seemed to be lying on its side; taking a left turn and then right, I found a door kept ajar at the other end. I opened the door to be greeted by a drizzling and dazzling light and on the creaking noise, bats rose, fluttering and falling down, bumping against the darkness. The ill-odour of dung shards engulfing the ambience, I pounced on and caught hold of a figure standing in the silhouette. The figure tightened its grip over me, the aroma of jasmine from its tresses of hair filling me thoroughly. It was Malli, my companion in the hide-and-seek game. I was dumbfounded for a few moments. “You felt scared?” she whispered in an intoxicating tone and began playing on my body. The odorous wet of her face being pressed against mine left me too dazed.

As I was standing still in disbelief at my wits’ end, she was playing several mysterious games on my body. Against the backdrop of jasmine odour, the pleasant smell wafting from the screw pine flower blossoming on the banks of the pond and the smell of dung in the deserted room, she and I metamorphosed into magic symbols and began playing a weird game.

One bad day, Malli did not turn up for the game. I was shell-shocked to learn that her family had migrated somewhere.

I chose the cross-sectional lines branching off in the symbols as if this were the only way to reach out to her. The dots above and below the lines winked at me as if my life was hidden there.

During school holidays, Muthu and I used to go to the dhobi ghat where the washed clothes were left drying up and do the work of segregating the clothes with gusto, identifying them with the help of marks.

A peculiar space would unfold in the matrix of the adventurous search in my favourite game of hide-and-seek. The same kind of journey of segregating the ‘washerman marks’ on several garments sparked a fire within me, the Vannar symbols branching off and swirling. Whenever I was ecstatic and exalted while unraveling the knots in the game of puzzle, that is, the game of separating people’s clothes imprisoned in the symbols, it felt like a journey through the puzzling labyrinth emitting a brownish odour, where I would meet Malli.

I was wandering about in the forest of symbols, like a mad man.

Muthu’s father used to segregate the washerman marks and through the elucidation of each and every symbol, he identified human faces and the images hidden behind the faces. That rare vision taking on the colours of a puzzling language created in me a planet of miracles. The weird space of that planet, swirling like a vortex in me, taught me that the secret of my life was to encounter the challenges of the game of puzzle.

I was treading the domes and squares of the symbols swirling in cross-sectional lines. The pupils of my eyes got torn at the moments, that he hinted at, of the mankind’s heredity and culture slithering in the space of symbolist lines. In an entirely different planet, Malli and I roam about, playing the hide-and-seek game, with a new and fresh language.

But Time uprooted me and hurtled me into the cruel reality, pushing my fantasy, hide-and-seek game, linguistic symbol and Malli too far away. I had forgotten the symbolist songs sung in the new planet, Malli memories and also the hide-and-seek game till Italo Calvino catapulted me to the world of fantasy.

In the novel ‘The Castle of Crossed Destinies’, Calvino crafted a conversational possibility through the Tarot cards, creating a new lingo.

That was a vicarious journey that led me back to the vision of my symbolist language. The pupils of my eyes that Muthu’s father had torn changed into the Egyptian Eye of Horus. My Malli aka Ludmilla is cascading as Yoruba Opon Ifá, Aztec sun stone, the predictive stones called ‘Muthezh’ in our native jargon, and Tarot cards.

************************

As I was unfolding all this stuff about symbols and their hidden meanings, linguistic and cultural, she was so carried away by my eloquence that she pounced on me and showered me with kisses in a tight hug. O my God! It felt like a journey to a world of bliss.

This kiss is no inferior to ‘protoplasmic kisses’ described by Santiago Ramon y Cajal, the Spanish Father of Modern Neuroscience.4

In the following weeks, we both began creating a new language based on the weird symbols circulating in the Vannar lingo. Kisses were on the upswing.

We travelled into the interior villages in our country and interacted with washermans. Ludmilla took notes. At one point of time, we began speaking in that language.Though initially there were hiccups, over the days we picked it up and turned highly eloquent. Our relationship grew in intensity; and so did the kisses.

However, I observed a particular feature. As Ludmilla’s lips engulfed mine and tasted the sweetness of kiss, I felt something uneasy; something that I could not pinpoint exactly.

One more peculiar thing happened. She was reading Enrico Fermi’s book and then, I asked her if she liked Fermi. She blushed and said, “Do you know about Fermi. I am quite eager to learn about the 'Fermi paradox'.”

“I just know it superficially. I am not that interested,” I said and walked away.

One day, we were in Dhanuskodi, the sea-devoured city in our country. We were walking down the seashore once ravaged by a heavy storm.

“It felt like being in Herculaneum in our country,” she said, leaning on my shoulders. As her breasts tickled my ribs, I said poetically to her that the soil odour of its sister city, Pompeii, wafted through the air.

As a volcano of passions was raging within us, we rushed to our room and took off clothes. Her swelling breasts heaved uncontrollably; I pounced on her and caught hold of her lips with mine. Then, a shock struck me. The taste of her lips was not human. Shiver ran down my spine. Slowly descending, I buried my face in her breasts. It somehow felt mysterious. O God! Her left breast was without its nipple, glosssy!

My head spun and I started looking around. Richly grown breasts! Suddenly, our Tamil poet’s line “Human body is just a bag of winds” struck me.5

I rose up and ran out of the room. With perverse thoughts coursing through my mind, I roamed about in the ruins of Dhanuskodi. As my legs got tired of walking, I returned to the room, fear still hardly willing to leave me alone.

She was missing. Only my travel bag was there in the room. Her things were not to be seen. A letter was fluttering on the bed.

The letter read:

“I thank you for the creation of a new language. I say goodbye. We can meet when time travel becomes possible. As a parting gift, I leave behind the book of Enrico Fermi. I sign in your favourite name - Ludmilla.”

************************

Thereafter, I was wandering about like a mad man in the labyrinth of symbols. Fermi’s book led me to a long journey. After a sweet and mixed journey through Albert Einstein, Fermi paradox, extraterrestrial life, civilization on other planets, science fiction, Stephen Hawking, and time travel, I stand before now, writing this column.

How can I forget the name that revolves around the symbols in the script in that anonymous mail?

You can wonder whether all these had happened really or are just a figment of imagination.

But I hope Ludmilla will one day come and say it’s all true.!

--------------------------------------------------------

Notes:

1. “Our Lord glanced and so did she.” This line was written by our Greatest Bard Kamban in his epic ‘Ramayana’ in the scene where Lord Ram and his consort Sita met for the first time in their life.

2. “Whoever are my mom and yours”; it is a famous line from a poem in ‘Kurunthogai’, a work of the glorious Tamil Sangam literature. The poem celebrates love that transcends all barriers such as language, race, family affinity et al.

3. Seven in the third line, in fact, means the seven worlds mentioned in our mythology.

4. ‘Protoplasmic kisses’ described by Santiago Ramon y Cajal, the Father of Modern Neuroscience. He said that every neuron in the brain wants to find its identical companion and the painful incident of finding its mate culminates in the protoplasmic kiss no less deeper than that exchanged in any classical love.

5. Tamil poet, who wrote the line “Human body is just a bag of winds,” is one of the famous sage bards, known as Pattinaththar.

Translated by : Maharathi

Gouthama siddarthan is a well renowned short story writer, poet, columnist and critic in modern Tamil literature. He has won many critically acclaimed literature prizes. He got written and published 17 books of stories, poems, and essays.

Writing for the past 30 years, he has now started to write in international languages. Very recently, his works has been translated and published in English, French, Spanish, German, Italian, Chinese, Romanian, Russian, Bulgarian, Portuguese, Arabic, Greek, Singhalam, Shoana etc.

One book of these "Political travails of Time travel" has received International attention..

He is also the editor of literature magazine “Unnatham”. 40 magazines have come so far. The magazine focus mainly on the modern literature around the world. Special editions for Italo Calvino, Milandro Pavic are few among them. “ The contemporary modern literature around the world” is the recent one to name with. It got the best magazine of the year award in 2018.

He, who continuously monitoring the modern literature of the world, is currently writing columns for French, Spanish and Italian magazine.