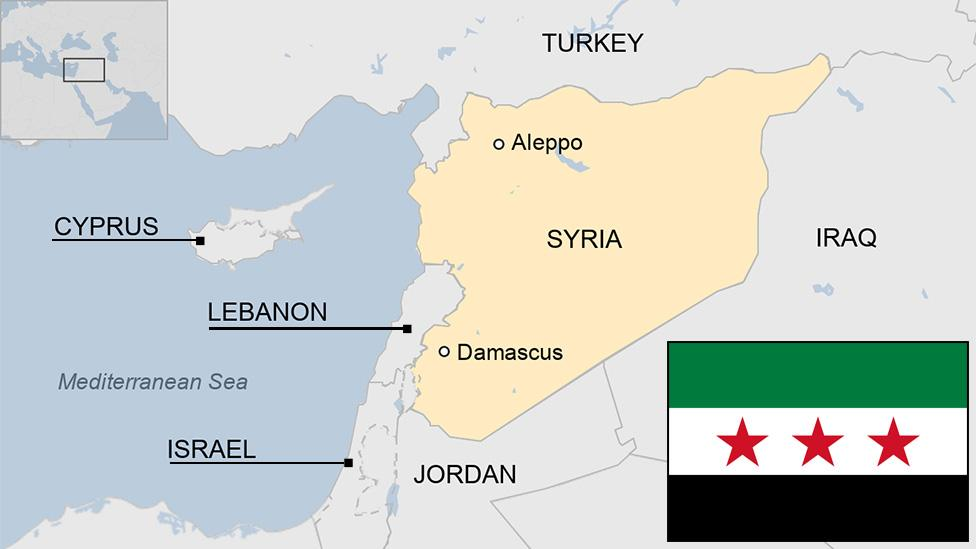

Until the night of June 2, 2025, the fate of foreign jihadists in Syria, under the leadership of Ahmad Al-Shar’a, remained a hotly debated topic among Middle East analysts.

By Ali Albeash

Following the collapse of the Assad regime in December, a wave of cautious optimism spread. Supporters of the new government insisted that the thousands of foreign fighters who had flocked to Syria since the conflict escalated in 2011 would be repatriated or otherwise removed, having supposedly fulfilled their purpose.

However, reality quickly complicated that narrative. The initial reaction of many regional governments to Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) seizing power was to shut their borders to Syrian citizens, citing the need to re-evaluate travel documents in light of the new political landscape.

As diplomatic channels began to open between Al-Shar’a’s regime and neighbouring countries, a consistent demand emerged from nearly every delegation: resolve the issue of the foreign fighters still active in Syria. Many analysts believed this to be an impossible task—one that might ultimately trigger the downfall of the new administration.

The Syrian government's justification was that foreign fighters made up more than half of HTS’s active military power, and without them, Syria’s fragile security infrastructure would collapse. That explanation failed to convince the international community.

On March 6, after a strategic attack by Assad loyalist remnants on General Security Forces (GSF) positions in Tartus and Latakia, a two-week spree of massacres targeted the Alawite civilian population. The worst atrocities occurred between March 7 and 10. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported over 1,778 civilian deaths, including women, children, and elderly victims, because of explicit acts of religious and ethnic cleansing.

Amnesty International labelled the events a war crime. At the same time, a detailed report compiled by Syrian human rights activists in Europe and presented to the UN Security Council named the militant factions involved. Audiovisual evidence confirmed that most of the perpetrators were foreign jihadists, many of whom continue to occupy military bases and checkpoints along Syria’s western coast.

Two high-level diplomatic encounters dramatically intensified international pressure on Al-Shar’a to expel these fighters. First was his unexpected visit to Paris, where he met with President Emmanuel Macron and received a list of France’s conditions for diplomatic support, chief among them, the expulsion of foreign militants.

The second was an even more surprising meeting with Donald Trump during his visit to Saudi Arabia, where the U.S. president met with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. The meeting ended with Trump promising to lift longstanding U.S. sanctions on Syria, on the condition that Al-Shar’a removes all non-Syrian jihadists from the army.

One would assume that by now, some foreign fighters would have been sent home. But that is far from the case. When the Syrian National Army was restructured, at least six foreign fighters were promoted to high-ranking positions, including colonel and general.

Video footage has even circulated showing official ceremonies where fighters were promised Syrian citizenship as a “token of appreciation” for their service. Some were told they could bring their families to join them in the “holy land of Sham,” about a specific Hadith promising a reward to those who wage jihad there.

For a brief time, hope returned to analysts and activists who believed the new government would lean on the International Coalition Forces to target extremist holdouts. Several reports confirmed precision airstrikes on foreign fighter enclaves, lending weight to the idea that international conditions were more than mere rhetoric. Many assumed it was only a matter of time before Syria would be cleared of foreign-born fighters.

Then came the shocking announcement that a whole unit of Uyghur militants would be integrated into the Syrian Army’s 84th platoon—with public endorsement from the U.S., according to Ambassador Tom Barrack. This development suggests that a backdoor arrangement might be at play, possibly linked to broader geopolitical tensions between the United States and China.

After all, relocating Uyghur fighters far from Chinese borders serves American strategic interests, especially given Beijing’s fears about their return.

Currently, estimates suggest that jihadists from 50 to 72 countries are still active in Syria. Their home nations do not want them back. And as interviews reveal, many of these fighters have no intention of returning. Expelling them without reintegration would likely drive them into ISIS’s ranks, exacerbating Syria’s already precarious security situation. Yet retaining them in the army risks a power imbalance, possibly even a future coup if the state is deemed insufficiently Islamic.

What, then, can be done?

Since taking power, the Al-Shar’a regime has been viewed as part of a broader project to establish a Sunni Crescent, stretching from Turkey to the Gulf, aimed at eliminating Iran’s three-decade-long regional influence. During U.S.-Iran peace talks, Washington demanded that Iran dismantle its militias, notably Hezbollah in Lebanon and Iraq.

This was confirmed when the U.S. invited Kurdish leader Masoud Barzani and Iraqi officials to discuss the Iraqi military landscape after forcibly disbanding Iraqi Hezbollah—a move intended to cut off Iranian influence through Iraq.

But should Hezbollah fall, a security vacuum will emerge—one that ISIS could easily fill. Analysts suspect that the foreign jihadists in Syria may become the backbone of a revived ISIS force. As history shows, their ideological drive makes them prime candidates for a renewed campaign against Shiite populations, which would lead to new demographic changes inside and around the capital, Baghdad. A similar scenario could unfold in Lebanon, although past failures suggest such efforts may prove futile there, even when aided by ISIS sympathisers in Northern Lebanon.

If Syria’s naturalisation policy for jihadists continues, the country could soon witness the arrival of thousands more foreign Muslims. In just five years, Syria may be transformed into a global epicentre of jihad and Sunni militancy. Whether that becomes reality or not depends, in large part, on imagination and the unpredictable nature of the games.

Ali Albeash is a physician and researcher specialising in artificial intelligence in medicine and public health. He holds dual Master’s degrees in Epidemiology and Chronic Diseases, as well as in AI for Public Health, from Aix-Marseille University. Ali is a published author, translator, and essayist, and has been engaged in Syrian social activism since 2013. This is his first contribution to The Liberum.