The cracks of division amongst the Iranian diaspora are already exposing the fallacies of a homogenic narrative often present in the Western media. Recent incidents surrounding various Iranian diaspora protests underscore how the simplification of diverse social and political voices risks obscuring deep-seated disagreements about the country’s future. These divisions can be seen as an early warning. Any post-Islamic Republic transition that fails to account for Iran’s internal pluralism may lead to a volatile and prolonged period.

By Turkan Bozkurt

Rallies meant to project unity have instead revealed competing visions of what “Iran” should mean after the Islamic Republic. A widening gap already separates many diaspora segments from those living inside the country, shaped by different incentives and political realities.

When demonstrations in democratic settings, where dissent is legally protected, still fracture into intimidation or sporadic violence, it should be read less as an aberration than as a warning signal. Homogenising inherently plural political demands by Iranians may lead to destabilising and violent domestic fights over what comes after the Islamic Republic.

Consider one anti–Islamic Republic rally in Los Angeles. A driver in a U-Haul truck displaying placards reading “No Shah. No Regime. USA: Don’t repeat 1953,” alongside “No Mullah” and “No Shah, no (supreme) leader,” was confronted by demonstrators who climbed onto the vehicle, pulled down the signs, and broke the windows.

In footage circulated from the scene, the car began moving towards the crowd. At the same time, no serious injuries were reported, and the driver and truck were later surrounded and struck again as police attempted to restore order and began an investigation.

The phrase “Don’t repeat 1953” refers to the overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, who had come to power through constitutional politics and sought to nationalise Iran’s oil industry, which the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company then dominated.

The nationalisation crisis collided with British and American strategic and commercial priorities. In 1953, the CIA and MI6 backed a covert effort, widely known as Operation Ajax, that helped remove Mosaddegh in a coup d'état to install the Shah’s authority.

The Shah was increasingly reliant on external support and on a political order that relied on coercive institutions to contain dissent. Declassified records and historical accounts have documented foreign assistance in building Iran’s internal security apparatus in the years that followed, including support for the creation and training of SAVAK, the Shah’s intelligence service, which became synonymous with surveillance and torture of political opposition.

In Toronto, a similar pattern surfaced. During one rally, a minority-rights activist who chanted slogans opposing a return of the Shah was confronted and assaulted by monarchist demonstrators. Video from the scene appears to show him visibly injured and bleeding, while the person filming challenges the crowd, who were chanting denunciations of “three corruptions” (the clerical establishment, leftists, and the Mojahedin).

After asking how such intolerance differs from the authoritarianism they claim to oppose. The activist continues to shout that “they don’t want democracy” and that the Shah will not return, only to be met with jeers and shouted abuse.

Elsewhere at the same gathering, demonstrators advocating federalism and decentralisation reported being attacked as well, with posters and flags torn; footage also appears to show scuffles in which an older attendee is shoved, and his phone is knocked to the ground.

A similar confrontation appeared in Istanbul, where demonstrators gathered near Iran’s diplomatic mission and quickly split into rival camps. One chanted “Javid Shah” (“Long live the King”), the other denounced the former monarchy in explicitly anti-Zionist terms. This clash stems from the political meaning of external alignment.

In the wake of the Israel–Iran 12-day war, Reza Pahlavi’s public posture, including his high-profile engagement with Israel and statements supportive of the U.S.-Israeli military action, has sharpened scepticism among many opposition constituencies who fear the involvement of foreign agendas.

His repeated appeals that started in June 2025, and were intensified over the past weeks, for Iranians to take to the streets and bring down the Islamic Republic appeared to generate little to no visible traction inside the country. This outcome has sharpened doubts about how much domestic constituency he can credibly claim.

In addition to these well-documented cases, incidents in Vancouver, Cologne, São Paulo, and Berlin also depict altercations between the monarchists and the Mojahedin-e Khalq (MEK). Founded in the 1960s against the Shah, the MEK participated in the 1979 revolution before breaking with Ayatollah Khomeini’s new state.

Its leadership later established the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI) and presented itself as a government-in-exile. But the group’s alignment with Saddam Hussein during the Iran–Iraq War has remained a defining liability, fueling deep hostility among many Iranians and complicating the MEK’s claim to national legitimacy.

A common thread runs through these diaspora flashpoints. The loudest faction, often aligned with pro-Pahlavi monarchism, treats pluralism as a nuisance to be managed rather than a principle to be protected. The justification is familiar: unite now to topple the Islamic Republic, debate minority rights and decentralisation later. But postponing those questions is not unity. It is an attempt to bury grievances and to predecide the boundaries of the new order.

To be sure, many monarchist supporters and other opposition activists participate peacefully, and broad coalitions are often necessary in moments of upheaval. However, democracy is not something you “install” after victory; it is a civic discipline practised in real time, especially toward those with less visibility and unpopular demands.

That discipline is already under threat amongst the monarchist opposition. In one widely circulated clip, the editor-in-chief of Independent Persian, Camelia Entekhabifard, rejects the language of “majorities and minorities” and frames national and ethnic minority rights organising as a separatist impulse.

The irony is that the Islamic Republic has long relied on the same tactic of equating peaceful cultural or federalist demands with threats to territorial integrity to justify repression and violence. Democracy is a system of power designed to protect the rights of those least heard. If opposition politics cannot even acknowledge the plural nature of Iranian society abroad, even among democratic countries where they reside, the risk at home is not only a turbulent transition. It is another form of fascist government that may present a democratic facade but harbours the same system of inequality and exploitation.

Pahlavi has already begun distancing himself from the “Woman, Life, Freedom” slogan, which he has removed from his social media accounts. The protests that took place in the aftermath of Mahsa Jina Amini’s death in 2022 are characterised as one of the most inclusive and effective movements in Iran’s recent history.

The denial of pluralism and inclusiveness should worry anyone who wants a stable, rights-respecting transition. If the language of inclusion is negotiable before authority is even won, what happens when the enemy is defeated, and the state’s coercive tools are within reach?

Calling something “democratic” or campaigning in the language of democracy while courting foreign patrons and endorsements does not, by itself, tell Iranians what kind of political order would follow the Islamic Republic.

Labels can be cheap. North Korea is officially the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and Congo the Democratic Republic of the Congo, yet neither name guarantees genuine checks on power or protection for dissent.

The more complex, more consequential questions are institutional. What enforceable commitments would monarchist leaders make to international human-rights standards? Would internationally accepted human rights be treated as non-negotiable constraints on government or as promises that can be narrowed once power is secured?

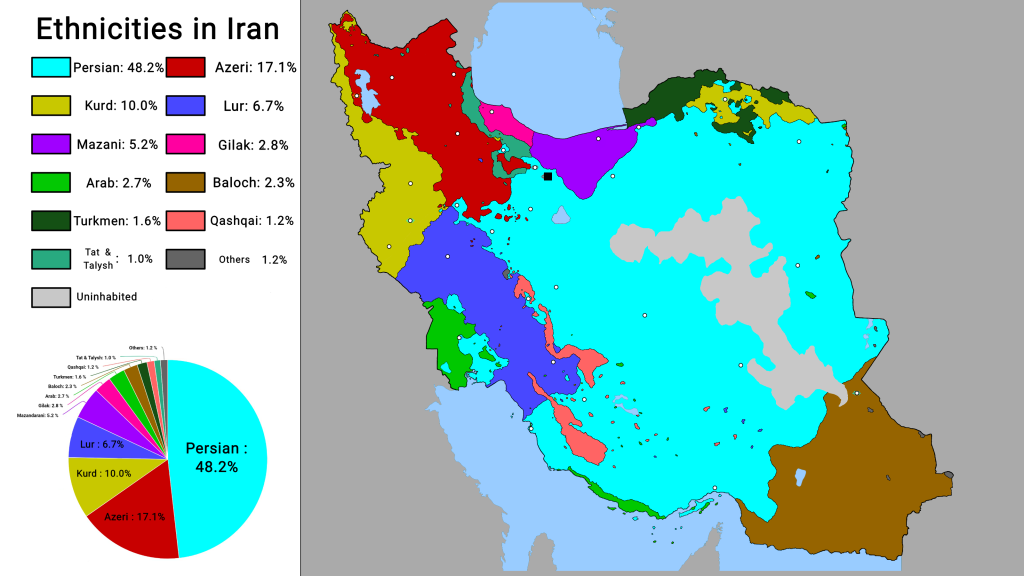

These questions matter because the “separatist” stigma deployed by both the Islamic Republic and some Persian-nationalist currents in the opposition often functions as a veto on legitimate claims for cultural, linguistic, and political recognition.

Yet international law is clear that “all peoples have the right of self-determination”. This principle is anchored in Article 1 of the ICCPR (and mirrored in the ICESCR). Democracies are tested precisely like this. This is not a test of how they treat majorities and the powerful, but of how they address unpopular demands through the rules and accepted norms of human rights.

Canada’s experience offers one instructive reminder. Quebec held sovereignty referendums, and Canada’s Supreme Court later emphasised that a clear vote on a straightforward question would trigger an obligation to negotiate within the constitutional order. The relevant comparison is not whether Iran should replicate Canada’s federal model, but whether Iran’s future politics can contain high-stakes disputes through institutions rather than street power.

If actors who claim to represent Iran’s future are already policing speech and narrowing the political community in diaspora spaces, it is fair to ask what guardrails would prevent those reflexes from hardening into state policy once power is within reach.

And that concern becomes more urgent when the analysis shifts from street politics to state collapse. The fall of the Islamic Republic as we know it or even the removal (or passing) of Ali Khamenei could create a power vacuum that today’s diaspora movements may be unable to fill.

Visibility abroad does not automatically translate into legitimacy at home. Meanwhile, domestic politics remains opaque, shaped by rivalries among political and security elites and by institutions built to survive crises.

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, for example, is not simply a military actor; it is an ideological and economic pillar of the state with deep patronage networks and loyal constituencies. Through structures such as the Basij, loyalty can be cultivated early and reinforced over time, socialising individuals into a system centred on their leader and the promise of martyrdom.

This process of institutional conditioning makes it unlikely for the large segments of the IRGC members to abandon their life’s mission and allegiance to the supreme leader to conduct a sudden and uniform defection in the event of a political upheaval.

The Iranian army, separate from the IRGC, may attempt to seize the moment by either conducting a coup d'état against the regime or trying to bring back central control at a point of collapse. Yet, similar to the IRGC, the army lacks internal organisation and political legitimacy to serve as a stabilising force.

The prospect of both institutions cooperating to present themselves as a unified, stabilising alternative remains uncertain. Rival chains of command and competing loyalties would make consolidating power and stability a challenge.

Finally, any transition will stand or fall on whether it earns the trust and cooperation of Iran’s national and ethnic minorities. With the recent wave of protests, we’ve already seen a hesitation from the Azerbaijani, Kurdish and Balochi regions to join Tehran. The implications of this silence extend beyond the current protest cycle.

While minority groups have long voiced their desire to end the current theocratic rule, many remain uncertain whether the light at the end of the tunnel is freedom or an oncoming train. The fear is that a post-regime order could reproduce older hierarchies under new symbols, as was done in 1979.

Any political transition that fails to secure the trust and participation of Iran’snon-Persian majority risks inheriting the internal turmoil seen in Syria and Sudan, where unresolved domestic divisions created prolonged instability and proxy wars involving regional and international actors.

Turkan Bozkurt is a human rights advocate and Deputy Director at IPEK Research Centre, with a focus on Middle Eastern affairs, gender equality, and minority rights. She has contributed to United Nations mechanisms and the Topchubashov Centre, and her analysis has been published by Geopolitical Monitor, EU Reporter, and JNS. She has also spoken at the UN and at international academic and policy forums, including the Economic Forum, MESA and NWSA. This is her first contribution to The Liberum.