When I first read The Museum of Innocence, it didn’t feel like a love story so much as a treasure hunt. For the antique lover that I am, these objects felt like clues scattered through a labyrinth, talismans I wanted to brush the dust off, and claim as if I’d discovered them myself from some private mazelike fleamarket of longing. He took obsession, that fragile, fleeting thing we usually hide, and sheltered it. He gave it glass cases and catalogue numbers as if he wanted to protect it. As if love, however misguided, deserved to be handled carefully. As if desire, once lived, shouldn’t be allowed to vanish without a trace.

The novel is slow, as museums are. You wander, double back, lean in close to read the smallest label, step back to see the whole frame. You circle back again because something tiny caught your eye. You stand too long in front of what others might skip, sensing that the simplest object is the one keeping the real story.

I felt complicit as I read through the pages. The book doesn’t ask you to judge the protagonist’s fixation but seduces you into sharing it. You become the accomplice, the silent archivist. The museum guardian.

And then I went to the Museum of Innocence in Istanbul

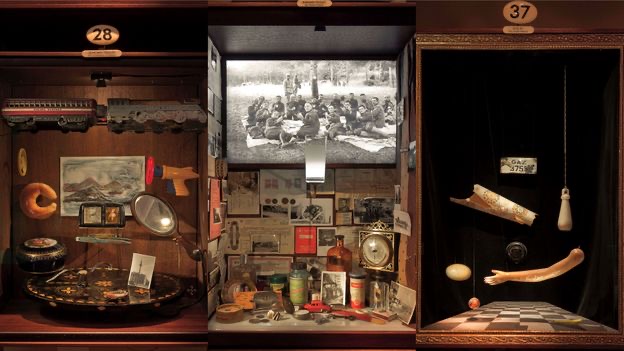

The physical echo of the novel where fiction had acquired walls, where the melancholy had lighting. What felt metaphorical on the page became tangible, almost devotional. Orhan Pamuk institutionalised obsession. He gave it glass cases, catalogue numbers, and the cold authority of preservation. He turned desire into infrastructure. I remember thinking: this is either genius or madness, and most possibly both.

And then I watched the Netflix series

The screen has no patience for ambiguity in the way literature does. It insists on faces, tones, and rhythms. It assigns breath to what was once a sigh. It codifies the pauses, names the silences. And in doing so, it makes decisions the reader had once been free to make alone.

Her character, so elusive on the page, suffered the most from this translation. In the novel, she is a paradox: at once passive and sovereign, distant yet gravitational. We never really know whether she is naïve, strategic, resigned, or defiant. That uncertainty is the story's voltage.

On screen, that voltage drops.

She becomes legible. And legibility is fatal to mystery.

Where the book allowed her to exist as an idea, as a projection surface for the narrator’s mania, the series insists on her physicality. She speaks too clearly and reacts too plainly. The ambiguity that once protected her complexity is traded for psychological neatness. It’s as if the camera, in its hunger to see, strips away the very opacity that made her powerful.

The novel trusted the reader to dwell in discomfort, to sit with an unreliable lover who confuses possession for devotion. The series feels more cautious, more didactic. It points to a critique in which the book basked in contradiction.

I loved the book because it made me complicit. I loved the museum because it gave longing shape without resolution. The series, by contrast, asked me to watch rather than inhabit.

And obsession, when observed from a safe distance, begins to look less like tragic romance and more like pathology. Some stories (especially those built like museums) are meant to be wandered through alone, to be breathed in, not displayed for collective scrutiny.

I guess my disappointment says less about the series and more about the peril of adaptation. Novels like The Museum of Innocence are interior by design. They unfold in the private corridors of thought, where obsession can bloom unchecked by external realism. The screen, however lyrical, drags everything into light.

And light can be unkind.