I’d recently watched an episode of Lost in Adaptation of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clock Orange (1971). Finally, I made up my mind to watch the movie, as horrendously violent and graphic as it is.

By Emad Aysha

The film is very misunderstood. In extreme cases, it’s a work of social satire, and thank heavens, the more graphic scenes are only in the first quarter. (Oliver Stone should have watched this 'before' making Natural Born Killers).

Enough distance is put between that phase and the last chunk of the storyline for you to get into it. That’s when the initial shock and miscomprehension dissipate, and the colour-coordinated visuals, haunting soundtrack and deadpan humour simply overwhelm you in a sensory orgy.

It’s simply one of the most well-balanced movies ever made, with minimal exposition that nonetheless fills you in on the state of the world, but in a thoroughly organic way. And not even through the narrator’s voice, Malcolm McDowell plays the protagonist, young hooligan Alex DeLarge, rather innocently.

FACE OF MONOTONY: The parole officers in this future dystopia have less sense than the criminals they are failing to reform. Talk about resume padding!

The story is set in some dystopian England besotted with flared colours and flared tempers, as gangs of disaffected youths make random attacks on people and each other. The first victim here is an old homeless person, and he bemoans how the young no longer have any respect for the old in this land of lawlessness where they send people into outer space instead of taking care of the needy.

Sex is afoot as Alex’s droogs drink milk laced with drugs at a special bar to get in the mood for the carnage of rape, assault and battery they engage in (refueling with mother’s milk). We also see how Alex's manhood is handled by his parole officer. (A very daft corrections official who drinks from a glass of water, not noticing the false teeth in it).

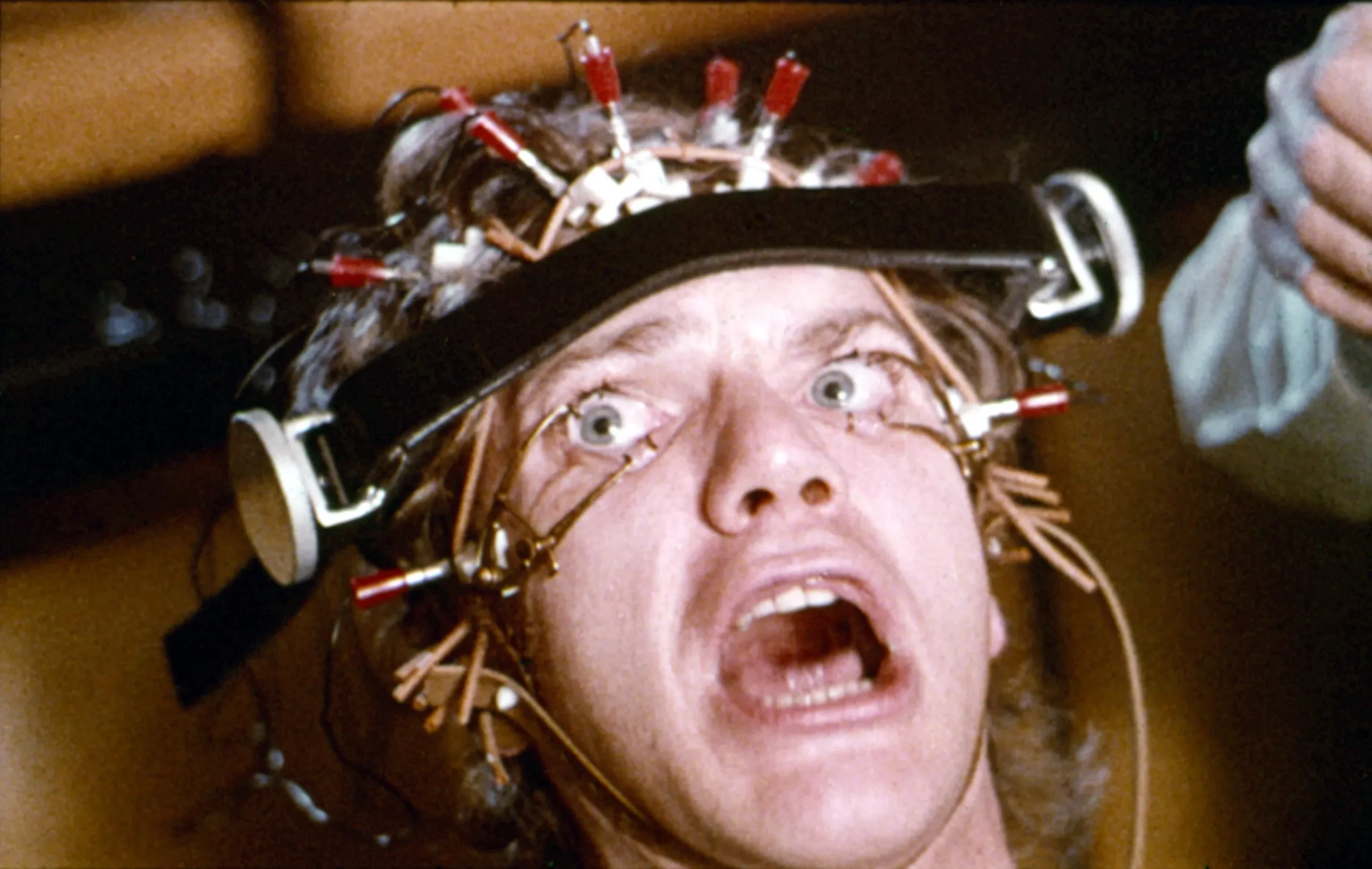

Alas, Alex goes too far and gets nabbed for murder, set up in part by his gang, and to shorten his sentence drastically, he volunteers for a brainwashing experiment. (The party in government wants to free up room for political prisoners).

He can’t hurt a fly from now on and is released, but his not-very-attentive parents shun him in exchange for a paying tenant, and, through a comedy of errors, he ends up in the house of one of his victims, a distinguished (and very stupid) writer. When the man realises who Alex is, he uses the brainwashing against him, which made him hate his favourite Beethoven piece. He tries to kill himself and fails.

The outrage in the press forces the government to unbrainwash Alex and get him a well-paying job so they can stay in power. Meanwhile, they legally dispose of the writer. And the movie ends with the screen song Singing in Rain, which he’d originally sung when attacking the writer and raping his wife.

The ending is meant to be ironic. Some criticism has been made of the movie because it was based on the American edition of Anthony Burgess’s novel, which doesn’t have the final chapter in which Alex doesn’t go back to his life of sadism and even bumps into a reformed former gang member who is now married into the upper middle class. But Kubrick found a way around this restriction.

All the government needed to do to win Alex over was get him a respectable place in society and pay him a little attention. Hence his obsession with Beethoven and why his gang wore bowler hats, dressed in white with cricket crotch protectors. They want to be part of the jet-set and ‘fit in’, forming their own miniature England in their peer group.

A rival gang they beat up, not coincidentally, are dressed like Nazis – all this recollecting England's glory days during the war. (Note the aristocratic hats in the brainwashing sessions). Alex almost sees himself as someone policing the streets, hence his references to cleanliness when beating up the homeless man and how scruffy the rival gang is.

GLORY BOYS: The leader of the rival gang before the better dressed droogs take him down. Talk about a society without 'class'.

By contrast Alex is an ass-kisser in prison, too, acting like an altar boy to win the favour of the authorities. Talk about a rebel without a cause. The fundamental failings in the world we see here are institutions, from the family to correctional facilities to the hospitals (the sex scene) and even the intelligentsia.

Everything reeks of neglect or self-interest. The writer who stupidly lets the droogs in is meant to be the middle-class intellectual, and he initially wants to help Alex when he lets him into his home a second time – none the wiser again.

According to Dominic Noble, Alex’s pet snake is an addition of Kubrick; not in the novel. I’d say it’s a phallic symbol (pointing at the nude on his bedroom wall) but also a reference to original sin. He sees himself as a Christ-like figure, persecuted or sacrificed.

Hence, the Christ effigies; four of them, like his gang, and dancing to boot. The lock mechanism on Alex’s bedroom door is meant to signify privacy and detachedness. His parents are blissfully unaware of his shenanigans, too concerned with keeping up with the Joneses.

When he’s in prison, he’s always referred to by number. The parole officer is only worried about how he will look bad to his superiors if Alex screws up.

His gang members also become cops and beat the shit out of him in revenge, with truncheons much like the aristocratic sticks they used when they were his underlings.

The screwball performances, which are very intense but also very natural, prevent this from becoming too nasty or too uninvolving. While still too violent, the movie is pure genius, one of the best-told stories on screen to this date.

One thing’s for sure. After watching this whenever you see a loud colour, you’ll run for cover – or join Greenpeace!