Bosnia’s Adnadin Jašarević (born 1967) deserves many accolades, not least of which is that he edited his country’s first-ever almanack for epic and science fiction literature, Prometheus (Prometej, 2000), which is now an established magazine.

By Emad Aysha

No wonder he has seventeen local and global awards to his name. He is the director of the Museum of the City of Zenica and has been organising the festival ‘Tragovima bosanskog kraljevstva’ (Traces of the Bosnian Kingdom) since 2006. He is also rightfully known as the founder of the first Bosnian school of comics, and many of his literary works have been turned into radio plays and books for the visually challenged. It's time for an intellectual showdown.

What does Adnadin mean?

“I was born and raised in Zenica, an industrial city in the heart of Bosnia. I was raised in the spirit of socialist morality: the good of the majority is more important than the good of the individual. Growing up wasn't easy, but it was peaceful, without restlessness.

The poor, everyday world was never enough for me. Even as a little boy, I understood how life in books is richer and more real. In the beginning and after, Gilgamesh and the Odyssey, a Flash Gordon comic book drawn by Alexander Raymond, and many other books, comics, and movies opened my mind to wonderful new, unknown realities.

As for my first name, it means Man Who Believe in Paradise.”

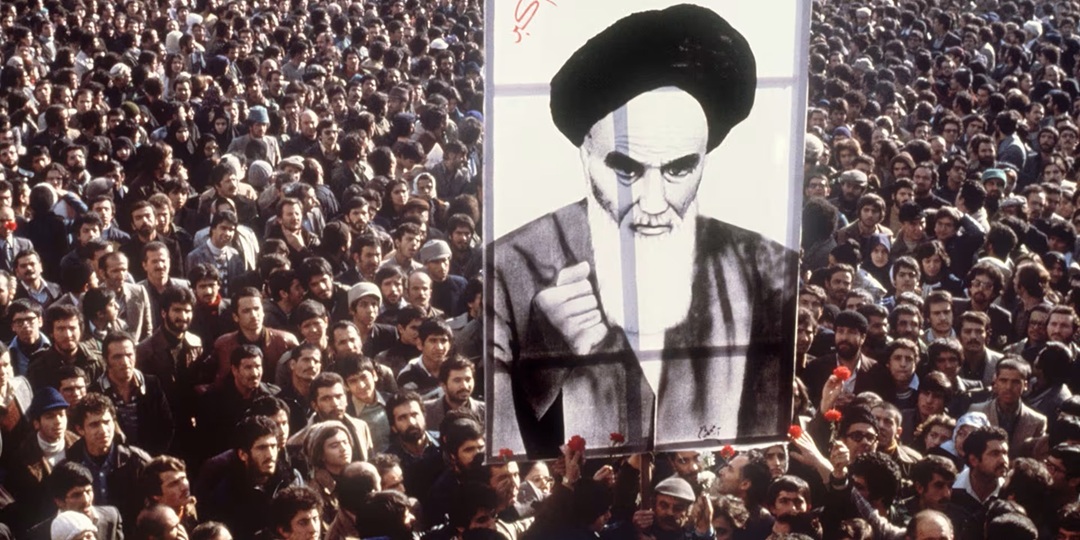

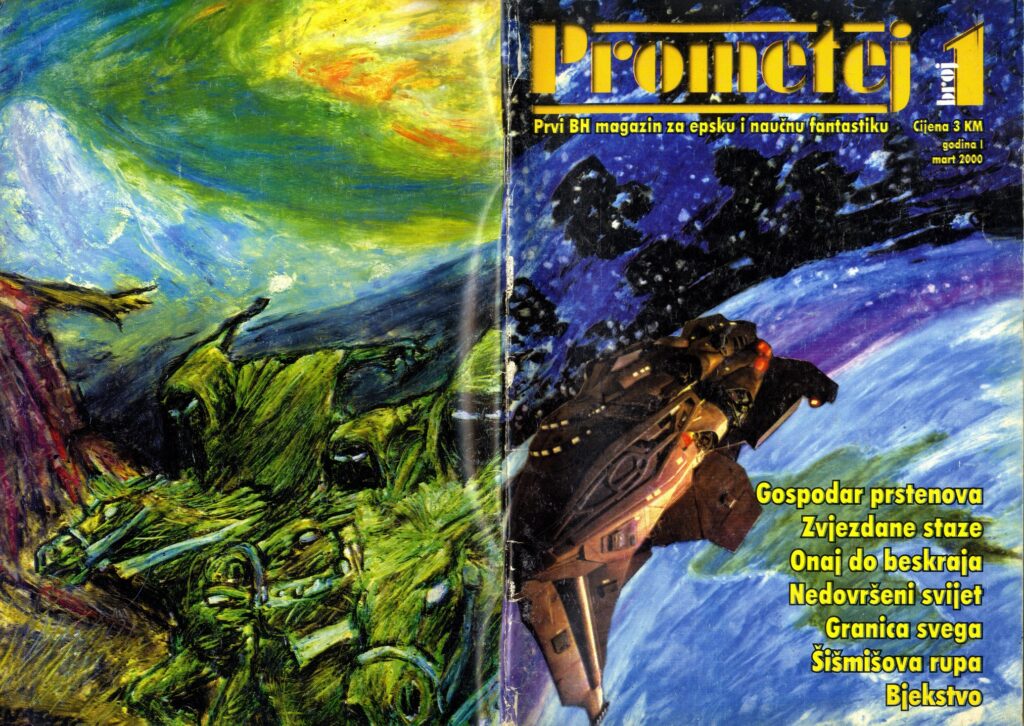

GIFT WORLDS: 'Prometej magazine' serving up a wonderous mix of science and fantasy, and from the less well documented parts of the literary globe. [Image provided by Adnadin]

How is comic book creation different from writing a story?

“My literary work is more affluent than my drawing work because of the problems. The drawing must replace the words. The cartoonist must tell the story clearly enough with the help of the drawing. In comics, the text aids a better exchange of action and ideas. At the same time, the word is dominant in literature, and the illustration may or may not serve as an unobtrusive addition or decoration.”

What themes do you pursue in your works, written or illustrated?

“In my youth, fantastic themes from mythology most often motivated me to write. My first hero, Ban Kulin, is half real, half fictional, and legendary. Later, in the fantastic novel "The Unfinished World", I deal with dreams from which reality emerges. As I get older, so do my themes. I write fantastic postmodern stories and novels; I absurdly deal with the absurd world: I erase temporal and spatial determinants, all boundaries, except those created by the human spirit. And comics, I prefer to draw fantasy and science fiction.”

Do you incorporate Bosnian folklore and myths into your work?

“From the beginning, my first book of stories, "In the Hall of Mirrors," is based on Bosnian, actually Slavic folklore. I placed our medieval ruler, Ban Kulin, in an environment full of fairies, dragons, werewolves, and other mythological creatures.”

Is art something that bridges cultural divides in the former Yugoslavia?

“Art is a bridge that brings artists together in the former Yugoslavia. But the truth is, artists did not even quarrel. We do not kill, we do not rape, we do not imprison people in camps. Therefore, culturally connecting artists in Yugoslavia after the war was not difficult. We maintain connections, organise festivals and help each other publish books.”

Is there a good market for comics in Bosnia? And do your comics sell well abroad?

“Bosnia is too small, and the market for comics is weak. I have never published comics abroad, except in neighbouring countries where people speak related Slavic languages.”

PICTURE PERFECT: Beauty is beauty of form and purpose, as the aesthetic and the heroic are things we all share as citizens of the world. [Illustration by Adnadin]

Any advice for comic book creators in the Arab world?

“I once managed to pull a short comic following that rule. It can work. Although, it is difficult to convey the hero's personality without a portrait. It needs more effort. If you are drawing from abroad, you should know that foreigners perceive the Arab world as exotic, as Scheherazade told us. So, no self-censorship.”

What is the sci-fi scene like in Bosnia? Does the almanack well represent it?”

“The Bosnian science fiction scene has never developed into a real scene. Only two authors have written and published significant works. The rest, a story or two. There is not much interest in this genre in literature, which is unusual for Bosnia. Therefore, this country is at the crossroads of cultures and mythologies and is very rich.”

Is Nicola Tesla a folk hero in Bosnian science fiction? And is there a sci-fi scene in neighbouring states like Croatia and Serbia?

“Many writers write stories and novels about Nikola Tesla. I can't say that he is like a character from folklore, but yes, it inspires writers. Goran Skrobonja from Serbia wrote the best story about Tesla in the novel "The Man Who Killed Tesla." Other authors are not particularly successful or innovative.”

A final question. Do they use fantasy or SF stories or comics at school in Bosnia?

“Comics are not included in education in Bosnia. As far as fantasy literature is concerned, rarely. My post-apocalyptic novel, "The Fellowship of Seekers", is included in school reading. As far as I know, it is the only domestic SCI-FI novel in education. As far as foreign writers are concerned, children read and study "The Lord of the Rings" and "Harry Potter".

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Gloria McMillan and Ahmed Salah Al-Mahdi for making this interview possible.