A funny story about a funny story: I was at the 54th Cairo International Book Fair (24 Jan-6 Feb) and refused to buy what ‘looked’ like an SF novel just because it was horror-dark fantasy, despite the advice of a sweet old lady that said I’d thank her once I read it.

By Emad Aysha

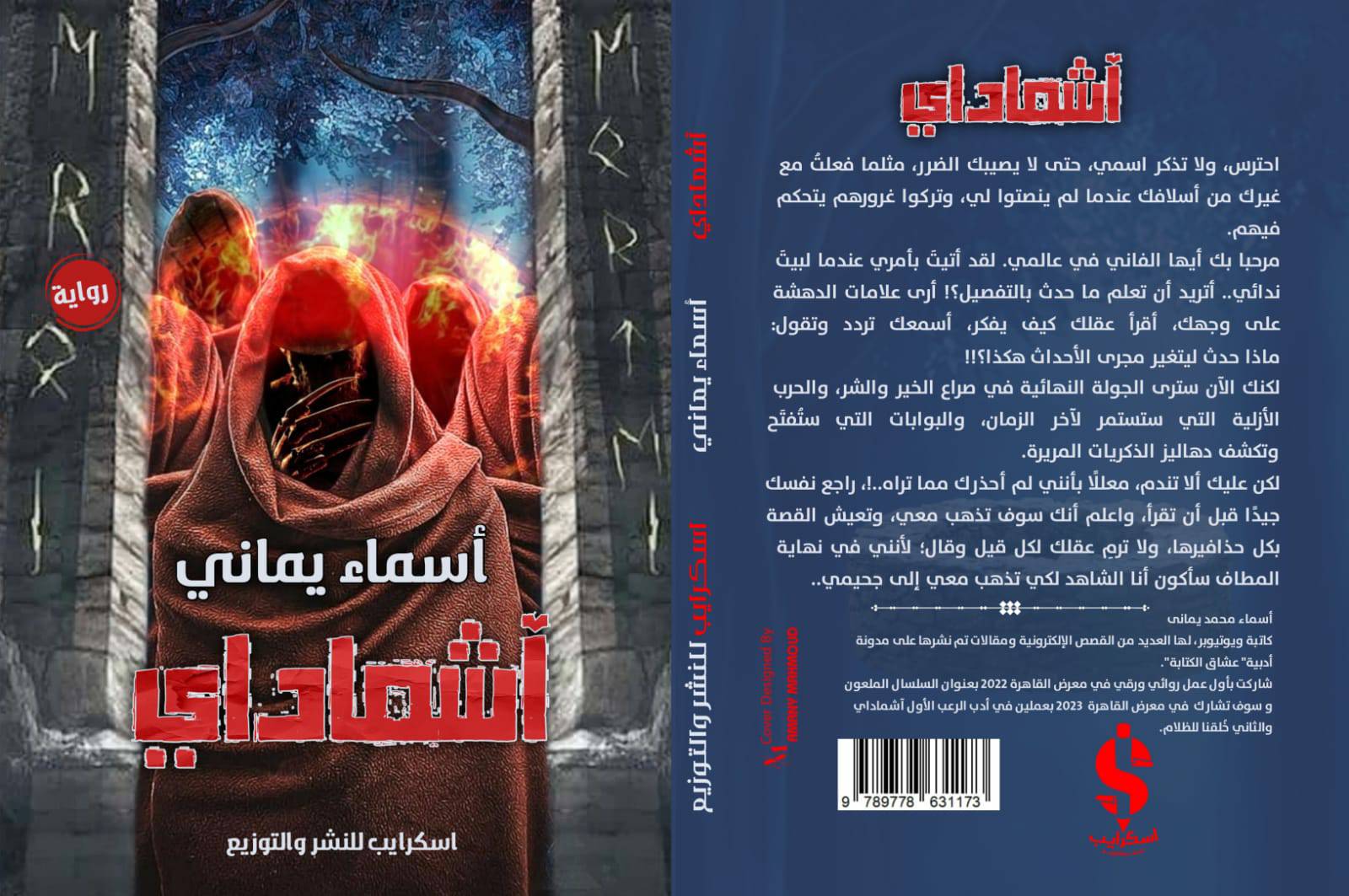

I went elsewhere, bought an SF novel that looked like horror-dark fantasy and the author, Asmaa El-Yamany (from Suez), insisted she walks me to her publisher. I found myself back where I started, Escribe publishers. I bought her novel, Ashmadie, and was in such a good mood while there that I got a fantasy novel with a sci-fi cover just for the fun of it!

The old lady had also explained that Ashmadie was a conspiracy thriller about the Masons, something I’m not into, along with supernatural horror. I make an exception for my good friend Ahmed Salah Al-Mahdi with novels like Reem, The Marooned Mirror and Morpheus, but I like my SF raw and hard. I also have a pet peeve against what I see as a form of ‘grafting’ of Western obsessions about ancient Egypt onto us Egyptians, portraying our distant past as unscientific and obsessed with human sacrifices and mystical cults.

Please don’t take my word for it; watch Young Sherlock Holmes (1985). It’s taken this long to disprove the myth of the ‘bride of the Nile’, so I have a right to be concerned. And there was a veritable explosion of horror books this year, with jinn and satanic references, and an awful lot of ancient Egypt SF, horror and fantasy stories too.

Fortunately, this little gem of a novel bucked the trend. The first thing that struck you about it was how well-written it was, with a fair amount of narrative experimentation. The opening words are actually by the malevolent entity, Ashmadie, making himself out to be a victim of fate and warning the reader not to continue with this text.

Then you move to a third-person narrative with the erstwhile hero of the story, Seif, holed up in a lunatic asylum for stabbing his wife Ghufran to death. His own brother testified against him. The man professes his innocence, can’t remember a thing, even that he’s originally a cop, and keeps having grizzly, mind-bending visions of people and places, with words being spoken to him by Ashmadie, telling him terrible things about himself and his poor wife. (More innovation here because you switch to his subjective perspective repeatedly).

The only person who takes pity on him is a young doctor there and then a fellow inmate, a beautiful and very European-looking woman named Dalia, who has been locked up under similar charges. Other oddities also abound about the nature of the crime and investigation, and these worry the young doctor but don’t seem to bother the top doctor at the loony bin. He has a job to do, and that’s good enough for him, namely, getting Seif back to his senses so they can execute the poor bastard!

That’s the second distinctive feature of this novel brand, Egyptian humour. Bureaucracy and incompetence and lack of supervision are everywhere. Seif is also very recognisable to the Egyptian audience because of his naiveté and misplaced romanticism, trusting women too much, while Dalia is in the can because her evil uncle and his favoured son wanted to steal her inheritance.

Seif and Dalia receive more harrowing visions and warnings of impending doom, and they steal a concealed text written in Hebrew and make a break for it, and we discover that Dalia is not what she seems. Her mother was a European Jew but a dutiful wife who raised her daughter to be a good Muslim.

Dalia decodes portions of the Hebrew text that talk of Ashmadie and Azazel, relying on the six-sided Star of David as a totem to activate these hidden powers. This is a welcome cry from the usual symbol in Western horror, the five-stared pentagram, and it’s even hinted here that the Jews borrowed this benign totem from the ancient Egyptians – further exonerating our past from the Satanist stereotypes of the West.

The third unique feature here is cosmopolitanism. Judaism is explicitly exonerated from the crimes of Israeli Zionism, and we then learn that Dalia’s mother was a victim. If anything, it is Dalia’s Egyptian family who are the Satanists, working for a Masonic-like cult organised centuries ago in Europe hell-bent on ruling the world and subjugating the Third World in the meantime by penetrating their societies and recruiting from the whirlpool of unemployed youths.

(Could Seif’s brother be one of those unfortunate, envious as he is of his successful elder brother? Wait and see). This foreign cult does the sacrificing, murdering women at six-year intervals, with Dalia as the ultimate sacrifice to usher in the Satanic apocalypse.

SHOPPING SPREE: Asmaa El-Yamany and yours truly at the Cairo international book fair. Nothing like a trick of fate to enlighten you about the future direction of the past’s literature!

I don’t want to spoil it for the reader, although I think the penultimate chapter was a bit rushed and had too many surprises. The important thing is that you feel nationalistically elated at the end, the heroes come out on top, and you realise the significance of some of their names – Seif means sword, and Ghufran means forgiveness or redemption.

So the novel thoroughly Egyptianizes Western tropes and genres, and stereotypes and turns them on their head in point of fact. The final lesson is the ease of genre-splicing going on here.

Talk to any Arab critic you like, pro- or anti-science fiction; you’ll find a curious overlap between SF and the detective novel, which ultimately is all about science itself – forensic evidence, cross-examination of witness testimony and rational argumentation in the courtroom. This is a detective novel, a horror and dark fantasy, and a romantic one.

Novels like this are a step in the right direction, and I was happy to find my ghufran from my conceited species of sci-fi cynicism through a book-buying runaround!!