Just recently got to watch a fantastic movie by director Ken Russell, Mahler (1974). It stars one of my favourite actors, too, Robert Powell, as the great composer Gustav Mahler (1860–1911).

By Emad Aysha

I’ve only watched three of Ken Russell’s masterworks, and each one is its own distinct person, using its own distinct visual and visceral language to get the point across.

In The Devils (1971), you have a dramatised account of the downfall of 17th-century Urbain Grandier, played by Oliver Reed with all his pomp and gratuitous sympathy. The dominant aesthetic here is that of ‘theatre’.

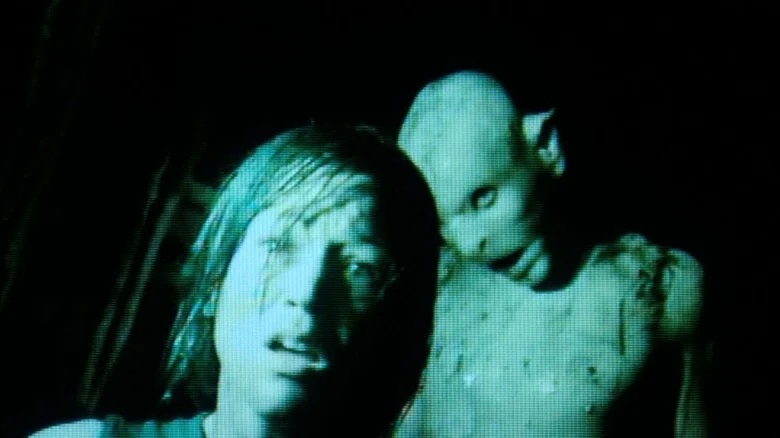

KANGAROO COURT: A screenshot from 'The Devils' depicting the trial of Urbain Grandier, as a Catholic sheltering Protestants. Hooded justice; how little has changed.

You feel like you’re in a play, with a flattish quality to the background, an emphasis on indoor sets, and people moving around minimally. It still is a movie, though, since you have plenty of external shots and other narratives than that of the erstwhile hero, and camera angles and motions that create a sense of depth and action.

I presume this was to create a sense of entrapment, of fate and impending doom. A world of stuffy restrictions and class designations, with a man who finally gives up on his sexcapades after meeting the right woman.

Again, it’s all a balancing act, and one that works perfectly. Altered States (1980), by contrast, is a psychedelic science fiction movie about a scientist pushing himself to destruction, taking a drug that allows his consciousness to travel backwards in time to the very beginning of the universe.

In the process, his own body also travels genetically backwards, morphing into a prehistoric person, then even farther back to merge with the inanimate universe. It’s a mind-bending movie but also a love story as the scientist’s ex-wife is the only thing that brings him back to this world.

The issue again is how the story is told, more subjectively than in The Devils and with lots of different locations, indoors and outdoors. The aesthetic here is flared colours, of subdued energy in the cosmos and the forceful personality of someone trapped in a suffocating job and personal life, as he sees it. (Dope that he is).

Not to mention a man who lost his faith, someone who looks for certainty elsewhere – in this case, science. Then we have Mahler, a movie that is all about smoke and mirrors, about tricking you into doubting everything you see because you can’t tell if it’s the composer’s imagination or not.

EMOTIONAL THERAPY: Blair Brown and William Hurt (RIP), like the Madonna and child in one of the few non-psychedelics scenes in 'Altered States'.

The focus is on the person of Mahler, of course. Still, his delectable wife, Alma, played joyously by the violently blonde Georgina Hale, gets her own subjective sequences, and boy, do you come to hate her husband many times throughout the movie.

The story takes place on a train, with Mahler waiting to be greeted by marching bands and adoring fans, recollecting his life up to this point, and how he messed up his wife’s life over and over again. Nonetheless, it is never, ever, compartmentalised.

The man used nature as both his refuge and inspiration, escaping the stuffiness, hypocrisy, and pathetic human clutter of various situations at home or at work to recapture a childlike innocence he had never thoroughly enjoyed as a kid.

Walking, running, riding horses, and swimming are his kind of thing, and the camera creates that anticipation of motion through being tilted and not being stiflingly horizontal. But there’s more to it than that. It wouldn’t work without a contrast, and in this case, it is his wife.

When she dances, in Mahler’s imagination, she’s like a nude gypsy dancer. In real life, however, she’s someone who enjoys being as still as a statue. She walks in a tight skirt that works like a Japanese kimono. (On his purpose, I suspect).

The colour contrast alone works wonders, with Robert Powell’s dark hair and Georgina Hale’s Aryan antics. They’re a match made in heaven, believe it or not, and the story does end on a positive note – although the composer’s days were numbered from ill health.

The film is almost as psychedelic as Altered States, but in a completely different way. In one charming scene, Mahler meets the Austrian emperor, and the man is clearly an eccentric, down to the white uniform he’s wearing.

MOMENTS OF TRUTH: Robert Powell as Mahler, a man who was a stranger in his own country, but inducted everybody into the land of the sublime. No visa required.

Then it turns out this is all a farce, the man is actually a fellow composer locked up in a lunatic asylum, and Mahler is playacting to help cure him, sadly to no avail. It’s pure genius, and you laugh your head off.

Another insane sequence is when Mahler has to go to the widow of the nationalist Wagner. Being Jewish, he has to convert to be accepted and promoted, and ‘prove’ his national loyalty, so to speak. It’s portrayed like he’s slaying a dragon in a cave, coming out instead with a pig’s head that he has to consume and ‘enjoy’. (Yuk!)

I can imagine what Mexicans are going through in the US, after watching this, bearing in mind that Aryan mythology coming out of Bavaria and Austria is a contradiction in terms.

But people swallow their pride and put on masks and makeup, literally in some cases, to do something beautiful and worthwhile and lasting—namely, music.

For a Briton, Ken Russell had a lot in common with Italian and French directors, with a love of statues and deep reds and greens. He had a Catholic background at one point.

The director gets into the hero’s character while seeing himself in the hero. The marriage angel/contrast is central to all three movies, too.

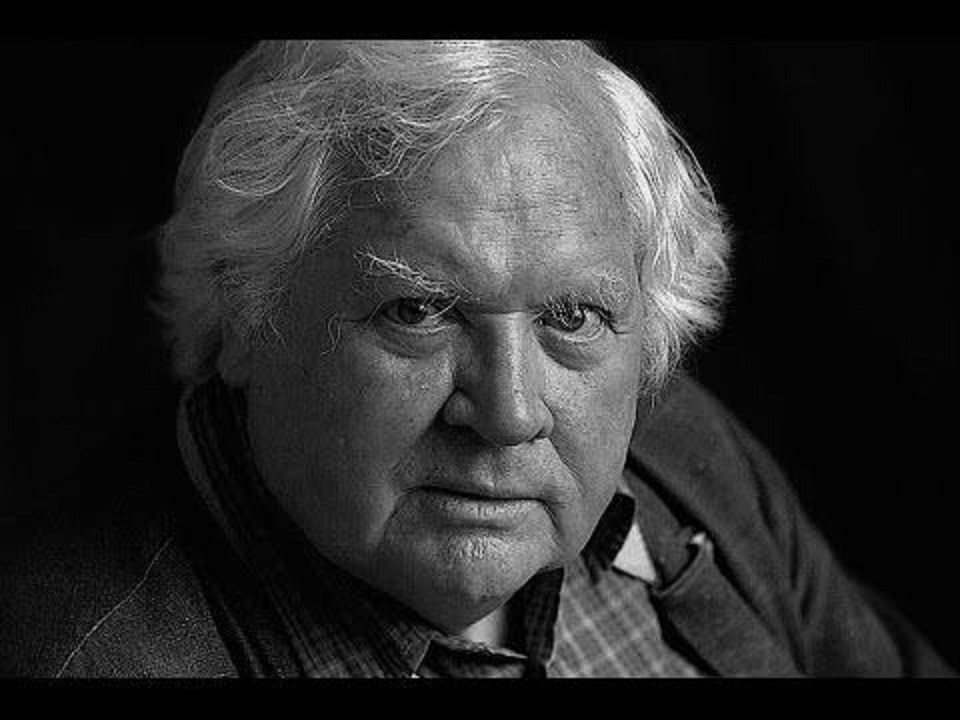

HEAVEN SENT: British director Ken Russell (1927-2011) left a legacy that won't be leaving our imaginations any time soon.

SF creatives seem to have a strange affinity for religion, the romantic lusting after what is unattainable in this world. Just look at Paul Verhoeven, and Mahler compares science to religion, too.

The job of the director is to make the invisible visible, in this case, love. The central law governing the universe of all three movies – if not the universe itself.