“I didn’t think very much about the man whose actions had put me in this place or about the men whose murderous ideology inspired him to act as he did. I thought only about survival, by which I meant not only staying alive but getting my life back, the free life I had so carefully built over the last twenty years.” (p. 72).

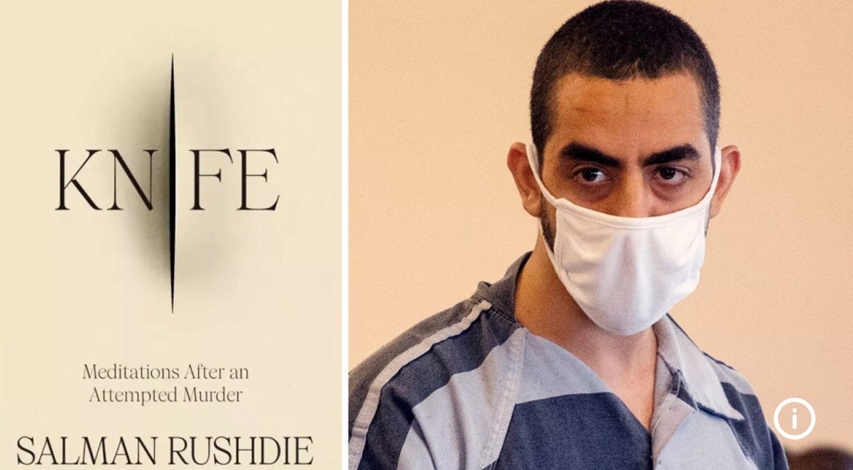

Perhaps this sentence is the most important from Rushdie’s recently published memoir, Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder. A title that refers to the knife with which Rushdie was attacked on stage at a literary festival in Chautauqua, New York state (August 12, 2022) by a young man, Hadi Matar, posing as a follower of Ayatollah Khomeini.

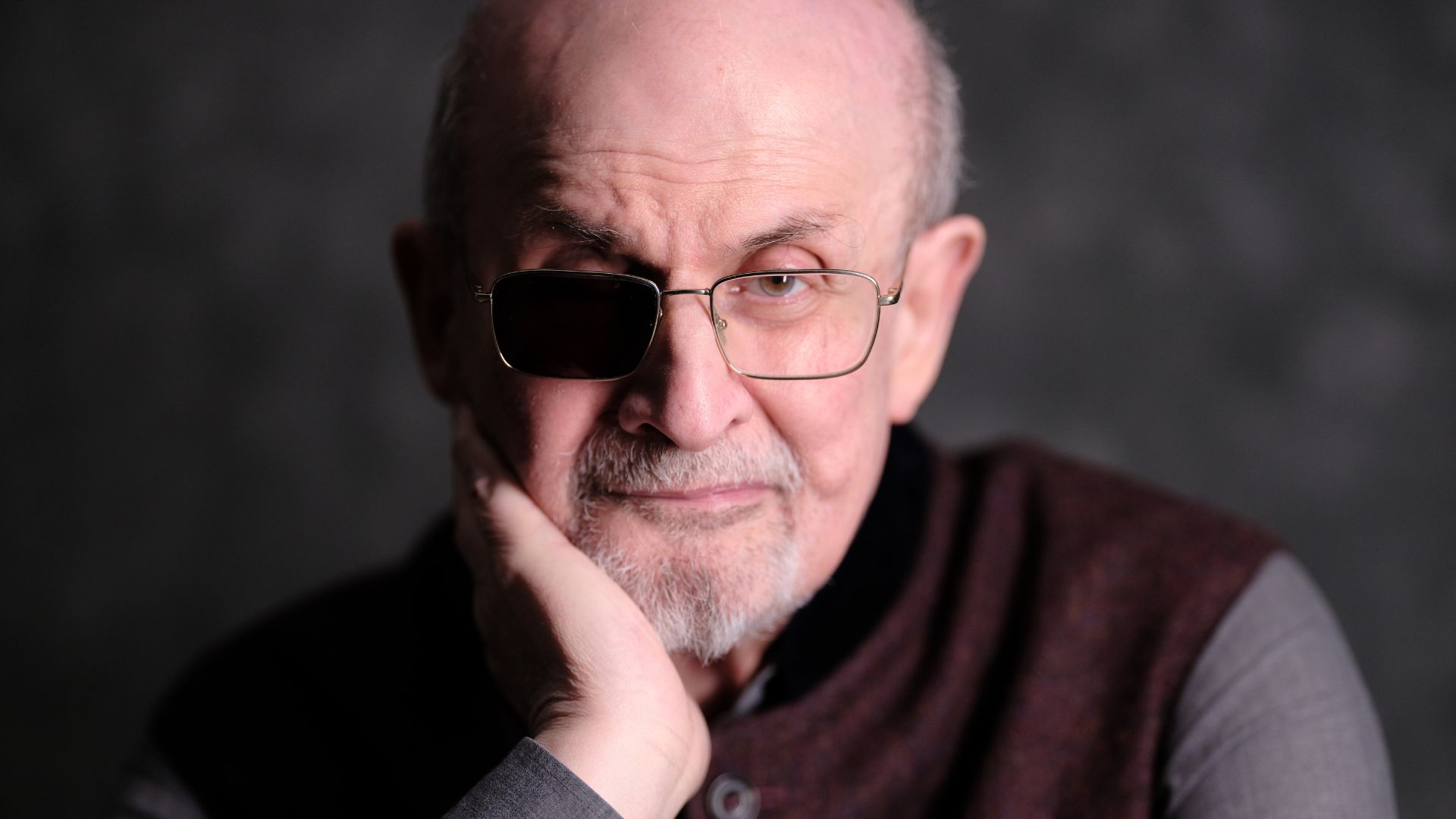

By Paul Cliteur

This left Rushdie facing another attack 33 years after Khomeini’s death sentence the British writer in 1989. Rushdie survived the attack, but he became partially disabled, and it caused him to lose an eye.

Knife (2024) resembles Joseph Anton (2012) from about a decade ago. It is a memoir focusing mainly on the writer's physical assault and its consequences for his life. That set-up lies the book’s strength but also its weakness. The strength: Rushdie knows how to tell an entertaining story.

In Knife, he follows events closely: how he is on the stage, and how he sees the attacker coming at him, what he experienced during the knife stab in his neck, how he lost consciousness. Who managed to put the attacker out of action? How bystanders and medics fought for his life. How he recovered in the hospital.

Rushdie was happy to be cared for by his new love partner, Eliza, whom he had been with for the last few years. The details are in the book. At the same time, while reading, wonder grows at Rushdie's choices in describing the events and the summary, if not absent, commentary on the most pressing questions that come to the reader due to his account.

How could it be that the most heavily endangered writer in the world could stand without any security on a stage in the United States, where an amateur assassin could attack him (it was a somewhat clumsy assassination attempt, as Rushdie rightly describes) who sticks a knife in his neck? What possessed this assailant?

What was his relationship to Islamist-jihadi ideology (these kinds of terms are hardly used by Rushdie, by the way)? What conclusions should we draw regarding the safety of Islam-critical authors in the Western world if, 33 years after a fatwa, an attack like this could and does still happen?

No attention to the murderer, including calls for murder

So, all these questions are not asked by Rushdie, let alone answered, while we are given minute descriptions of the pain he endured during the eye surgery required as a result of the attack.

Rushdie himself clearly states: “I didn’t think very much about the man whose actions had put me in this place” (p. 72). So whether Matar (whose name is not mentioned. Rushdie speaks of “A.,” which stands for “attacker”) was a convinced jihadist is not what Rushdie focuses on. Nor do “the men whose murderous ideology inspired him to act as he did” (i.e., Khomeini, among others) manage to entice Rushdie into any reflections (p. 72). “The men,” then - in my own words - are the religiously motivated and legitimised principals to the murder for hire with divinely guaranteed rewards.

Rushdie chooses the events described because “I thought only about survival, by which I meant not only staying alive but getting my life back, the free life I had so carefully built over the last twenty years” (p. 72).

Question marks

As one might expect from a talented writer like Rushdie, this makes for an exciting book. But also a book that leaves the reader with significant question marks. You have to draw your conclusions, as it were, about the hopeless situation we find ourselves in with the threat posed by the jihadist attack on freedom of expression.

That is precisely what it is: an attack on freedom of expression. It is not an attack on a person, the person Salman Rushdie. It is the attack on a principle, on the very principle of a free society. That attack, one might say, is also not perpetrated by a person, Hadi Matar, but by an ideology: by a complex of ideas that one can call jihadism, radical Islam, violent Islamism, Islamist theoterrorism (my term) – Let’s not dwell on the differences between these concepts for the moment - and which is enormously successful in the sense that it manages to survive, even grow in significance, about the civilised, reasonable, humanistic, atheistic, liberal thought that Rushdie himself represents.

Rushdie quotes a statement by Suzanne Nossel, CEO of PEN, an organisation representing the interests of literary writers. Nossel, referring to the attacker, had spoken of “the long arm of a vengeful government to reach into a peaceful haven” (p. 70). She had also mentioned “the frailty of our freedom” (Ibid.).

This, I would say, is the least one can say.

But Rushdie disagrees. Rushdie replies, “Don’t give him so much power, Suzanne. We aren’t so easily shattered” (p. 70).

Matar has power

Is that true? Rushdie makes it seem we can deprive Matar and his fellow attackers, or Khomeini or Khamenei (who did not revoke the fatwa), of their power by downplaying it. Rushdie even says of “A.”: “He’s just a dumb clown who got lucky” (p. 70).

I consider this comment, frankly, somewhat misleading. The fact that, 33 years after the fatwa, the liberal-democratic world has still not been able to bring a satisfactory solution to the problem of the threat of violence against the principles on which that liberal-democratic society rests is considered an alarming fact. And it indicates, however painfully, that “A.” has power, just like the now deceased Ayatollah Khomeini († 1989) who still rules over us. Whether we like it or not.

A necessary condition

I recognise that what I am saying here now is not providing the final solution to the problem. By this, I mean that what I am writing is not a sufficient condition for solving the problem. Nevertheless, this piece is not entirely meaningless because what I am writing here is necessary for solving the problem.

Only when we analyse the nature of the problem soberly and realistically do we have a chance of gaining sight of a solution. And almost everything we read on this subject, including the literarily beautiful and entertaining book Knife, seems wrong.

The worldview that legitimises Rushdie’s fatwa

The problem is that nowhere in his book Knife does Rushdie talk about the problematic aspects of the worldview that led Hadi Matar to his deed. Rushdie seems to want to put Matar very far away. He does not even want to name his attacker. As mentioned, he calls him “A.,” which stands for attacker.

For one thing, that may have personal and understandable reasons. It is psychologically understandable that you want to keep this figure “at bay.” You don’t want him to take over your life, so to speak, to control your life. If that happens, then he has won, not you. Rushdie wanted to continue with his life, to continue writing, even after the 1989 fatwa. We see that same attitude again in his new book: he wants to continue his life after the fatwa of 2022.

But beyond those personal reasons, Rushdie may also have strategic reasons for not elaborating on Matar’s worldview. He has - to put it euphemistically - not had a good experience analysing the problematic sides of Islam or Islamism.

We can’t blame Rushdie for his reluctance after 33 years of misery. After all, at a time of rising tensions between Iran and the Western world, Ayatollah Khomeini’s successor quickly composed a second fatwa.

The Western world and all countries where freedom of expression is defended, including the freedom to satirise holy books, are held hostage by Islamist theoterrorism, of which Khomeini is the leading contemporary exponent. And the Western world has not become a hair more “resilient.” Quite the contrary. The Western world is in an even greater state of confusion and thus weaker than in 1989.

Perhaps Rushdie also realises (sadder and wiser) that the chances of widespread support for his vision among the left-wing writing community are smaller than ever. Of course, one day, we must get out of this dilemma. For now, however, we are still in the Ayatollah’s grip.

Rushdie’s Knife was a fascinating reading experience for me. It also had a personal reason. The fatwa occurred in 1989 when I received my doctorate from Leiden University. That was also, in a sense, the beginning of my academic career.

I wrote a lot about the issues raised by this fatwa. About blasphemy (the complaint formulated against The Satanic Verses), freedom of expression (the value attacked by Khomeini’s verdict), and moral heteronomy (the view that God’s will, as interpreted by religious authority figures like Khomeini or self-appointed executors of His Will like Hadi Matar, has priority over non-religious ethics), but also about the solution: moral Esperanto.

In other words, my work takes 1989, the fatwa, and 2022, the knife attack resulting from the fatwa, as the source of inspiration for reflection on a significant social problem. What is that problem? It is the threat of violence and actual violence based on an ideology. That ideology also has a name. You can call it “violent Islamism” Or “jihadism.”

A good analysis of jihadism

To understand jihadism, one must delve into the mindset of Hadi Matar (or that of the Kouachi brothers, the murderers of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists or Anzorov, the murderer of Samuel Paty). So with me, Hadi Matar is not an “A,” a person whom one would prefer to try to keep as far away mentally as possible, but an object of study with which, whether we like it or not, we must engage intensely if we are to understand the problem we are dealing with.

Rushdie’s work reflects on the 1989 death sentence (e.g., 2012’s Joseph Anton) and the attempt to enforce that sentence from 2022 in Knife, which is an attempt to stay far away from ideology. Rushdie reflects on his own life. He repeatedly expresses the hope that the misery will end one day. He defends a novelist’s right to create fiction on any conceivable subject.

Again, Rushdie goes to great lengths to abstain from analysing the views of the person who formulated the assassination order and the persons (there were several attempts to assassinate Rushdie) who were willing to pull the assassination order into a seriously mandated execution. And because we do not learn those views, there is also no hope that we will ever be able to respond adequately to those views.

After all, you have to know who your enemy is. Only when you know that can you defeat that enemy. As Bernard Lewis wrote in The Crisis of Islam: Holy War and Unholy Terror: “Terrorism requires only a few. The West must defend itself by whatever means will be effective. But in devising means to fight the terrorists, it would surely be useful to understand the forces that drive them.” Knife is not a significant contribution to the norm Lewis formulates, although attractive for various reasons.

Not an incident but a precedent

Rushdie’s work is, in fact, an illustration of what I called “from incident to precedent” in the subtitle of my book Theoterrorism v. Freedom of Speech. After all, that’s the question: was Khomeini’s fatwa an “incident”, or was it a precedent for much more?

In my perspective, after 33 years, we can safely conclude that it was a precedent, not an incident. From the fatwa, we rolled on to the cartoons (2005: Danish; 2015: French) and from there to many other attacks that were jihadist-motivated. So, we are dealing with an unresolved problem. Rushdie’s hope that the fatwa would be some evil dream from which we could awaken has proved vain.