Few debates in Western Europe are as emotionally charged as the debate about Islam. It is rarely merely a discussion of theology; rather, it concerns identity, power, freedom, and fear. It is about the kind of society we want to live in. Too often, this debate is framed as a clash between believers and non-believers. This framing misses the point: the real fault line does not run between faith and disbelief, but between secular and non‑secular visions of society.

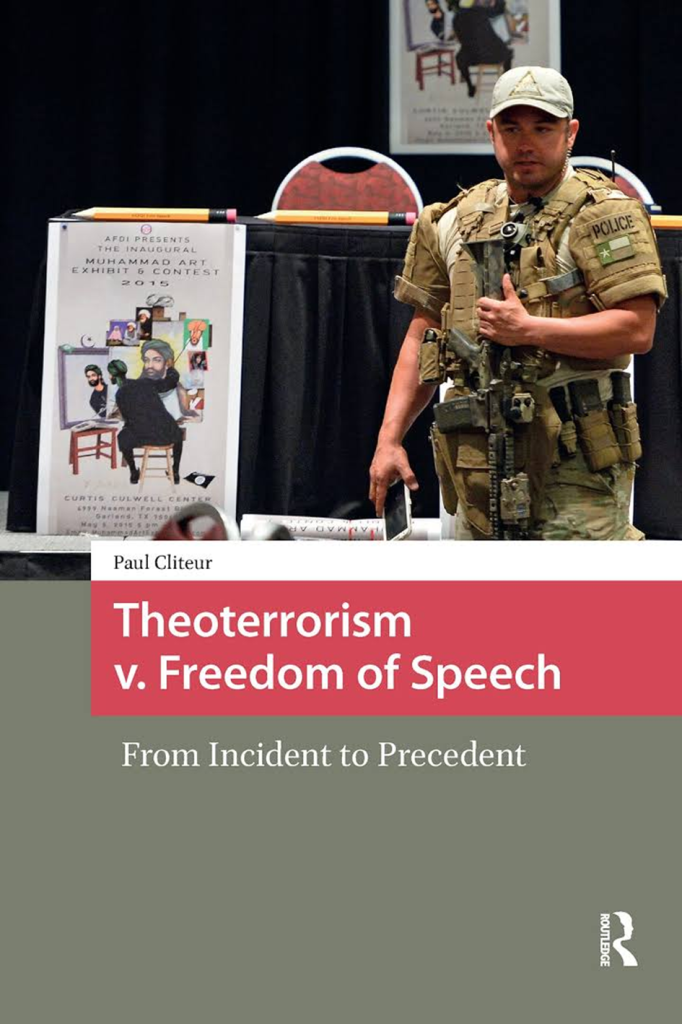

By Paul Cliteur

Secularism does not mean the eradication of religion. It means something far more modest and far more ambitious: that the organisation of society is not governed by religious dogma, but by the principles of the Enlightenment — democracy, the rule of law, and human rights.

Religion may inspire individuals, but it must not dictate politics or law. From this perspective, tension is inevitable whenever religious convictions claim political authority.

In the West, Judaism and Christianity have, for the most part, learned to coexist within this secular framework. To borrow Pim Fortuyn’s metaphor, they have passed through the “laundromat” of Enlightenment and humanism. Believers can practice their faith without challenging the foundations of the secular constitutional state.

With Islam, this process is less advanced. That does not mean that Islam is inherently incompatible with modernity, but it does mean that the friction is sharper, more visible, and more politically consequential.

To make sense of this friction, it is helpful to distinguish three attitudes toward Islam: pessimism, optimism, and realism.

The Islamic pessimist argues that Islam is fundamentally at odds with the Enlightenment. From this perspective, fundamentalism is not a distortion but a logical outcome of Islam itself. The distinction between Islam as a religion and Islamism as a political ideology is dismissed as artificial.

The conclusion is bleak: meaningful secularisation of Islam is impossible. Those who hold this viewpoint point to radical movements, terrorist violence, and authoritarian regimes in Islamic countries as proof.

At the opposite end of the spectrum stands Islamic optimism. The optimist believes that Islam, like Judaism and Christianity before it, can undergo its own Enlightenment. Why not? Religions are not static monuments; they evolve through history. From this viewpoint, Islam is not inherently more problematic than other religions. Its difficulties are explained by social, economic, and political circumstances rather than by theology.

Some optimists go further still: they argue that sharp criticism of Islam is unnecessary or even dangerous, because it fuels polarisation and radicalisation.

Between these extremes lies Islamic realism. The realist accepts that Islam can change — but not automatically, not effortlessly, and not without conflict. Reform requires criticism, debate, and confrontation with uncomfortable truths.

Judaism and Christianity did not become compatible with modernity without fierce internal struggles and external critique. There is no reason to believe that Islam will follow a different path. Realism, therefore, means hope without naïveté and criticism without fatalism.

This position may lack the dramatic appeal of optimism or pessimism, but it is precisely its sobriety that makes it persuasive. Those who believe that everything will turn out well by itself underestimate the resilience of religious traditions and the power of political interests. Those who think that change is impossible deny the dynamism of history and culture. Realism refuses both illusions.

At the heart of this debate lies freedom of expression. In a secular society, criticism of religion must be possible — even when it offends. Freedom of expression does not merely protect polite conversation; it protects the right to voice inconvenient and disturbing ideas. As George Orwell famously observed, freedom means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.

Yet across Western Europe, a different tendency is gaining ground. Criticism of religion, especially of Islam, is increasingly treated as morally suspect. Criticism of ideas is conflated with hostility toward people.

If every sharp argument is dismissed as racism or hate speech, public debate withers, and reform becomes impossible. A society that can no longer tolerate criticism of ideas has already begun to abandon its intellectual freedom.

The case of Geert Wilders illustrates this dilemma with uncomfortable clarity. In public discourse, he is often portrayed as a provocateur who fuels polarisation. But he is also the target of serious jihadist threats, including concrete assassination attempts.

This reality is sometimes minimised as a series of isolated incidents or explained away as the consequence of his own rhetoric. That is a dangerous logic. To suggest that critics should moderate their views to avoid violence is to accept, implicitly, the veto of extremists.

Where does such accommodation end? Should novelists stop writing critical fiction? Should cartoonists abandon satire? Should teachers avoid controversial topics in the classroom? If the answer is yes, then freedom of expression is surrendered not through democratic debate, but through intimidation. The secular state is transformed not by persuasion, but by fear.

From a realist perspective, this is not a personal problem of individual critics; it is a structural challenge for liberal societies. When criticism of religion is discouraged, fundamentalist currents are strengthened, not weakened. Reform is driven by confrontation and argument, not by silence.

This does not mean that all criticism is justified or that nuance is irrelevant. On the contrary, only an open and robust debate makes it possible to distinguish between legitimate criticism and prejudice. But such a debate can exist only if it is not strangled by moral taboos or legal intimidation.

The future of Islam in Europe is therefore not merely a religious question; it is a political and cultural one. The issue is not whether Islam can change, but under what conditions it will change. A secular Islam is conceivable, but only if secular principles are defended rather than abandoned out of fear or convenience.

Secularism is not hostile toward religion. It is a framework that allows diverse convictions to coexist without any single belief system dominating the public sphere. Religion can provide meaning, identity, and consolation, but it must not become the ultimate authority over public institutions. Without this separation between religion and state, pluralism cannot survive.

Ultimately, the debate about Islam is a debate about ourselves. About how much freedom we are willing to defend, how much criticism we dare to tolerate, and how much pluralism we truly accept. Islamic optimism without criticism is naïve; Islamic pessimism without hope is paralysing. Islamic realism is less comfortable, but it may be the only stance that does justice to the complexity of our time.

The task, then, is not to demonise Islam or to romanticise it, but to take it seriously as a religion in tension and dialogue with modernity. Those who acknowledge this tension—without denial or exaggeration—contribute to a more honest and productive public conversation.

In an age in which polarisation is tempting, and nuance is suspect, realism may well be the most radical position of all. It recognises that change is possible, but never effortless. It accepts that freedom is fragile, but never negotiable. It understands that the future of secular society is not guaranteed by history but must be defended anew.