The American unwillingness to further subsidise the war in Ukraine has unleashed a feverish debate in which Columbia professor Jeffrey Sachs plays a key role. Not that he is consulted so often by the (mainstream) media, but because of his enormous presence on social media. His influence is beginning to penetrate the mainstream discourse. Sachs’ recent encounter with American counterpart Francis Fukuyama made my eyebrows frown.

By Paul Cliteur

In short, Sachs states: “Talk to Russia, and negotiate about peace.” He also emphasises that European politicians must participate in this themselves: you can't expect much more from America. Sachs' lecture to the European Parliament on February 21st is a good start to understand his work.

Noteworthy: Sachs does not believe in an inherently aggressive and imperialist Russia. The reason for the invasion of Ukraine was Russia's annoyance with the expansion of NATO. Since 1994, the policy of the American deep state has been the expansion of NATO.

It does not matter which president there was (Bill Clinton, Bush senior and junior, Barack Obama or Joe Biden); they all did the same thing and did it wrong. Sachs advises granting Russia a buffer state between Russia and the Western world. Just as the Americans did not tolerate Russian missiles in Cuba in 1962, it is also reasonable to grant Putin his buffer state.

Based on leaked documents, it appears that America is constantly challenging Russia. The war in Ukraine is essentially a war between America (the “old America” then; the America of Joe Biden) and Russia in which America aimed to encircle Russia. As a result, the February 2022 invasion occurred. This American policy of continuous NATO enlargement has been pursued since Clinton in 1994.

With the new Trump administration this policy has come to an abrupt halt.

Pierce Morgan interviewed Sachs recently and had Francis Fukuyama respond to it. For those who do not know Fukuyama, he is a well-known American International Relations scholar best known for his work The End of History and the Last Man, in which he argued that the progression of human history as a struggle between ideologies was essentially at an end, with the world settling on liberal democracy after the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Fukuyama’s response to Sachs

Fukuyama’s response to Sachs' standpoints is quite blunt. Within seconds, he accused Sachs of parroting many Moscow talking points. It is essential to dwell on Fukuyama’s answer a little longer because it concerns how we should discuss matters of the utmost importance. In this case, matters of life and death.

This is an unworthy response from Fukuyama, as he begins, before giving a more substantive response, with nothing less than a disqualification of his colleague. Sachs is said to merely “parrot” Moscow’s points. Unworthy in essence: one should not ever do that.

Why?

Sachs has studied the conflict, written books, and is a prominent advisor to heads of state. He is a committed researcher. If you say of such a person that he “merely parrots” the positions of one of the parties in the conflict, then in a sense, you disqualify this person as a discussion partner. You accuse this person of scientific dis-integrity.

Can there ever be a reason to do that? Yes, but then you also must be able to prove, that is to say, prove, that someone has other interests than telling the truth. Then it would have to be the case that Sachs, for example, receives money from Moscow to propagate certain positions. Or that for reasons other than financial reasons, Sachs' interests are at stake in taking the positions he takes.

But there is nothing to indicate that.

Sachs is a professor at Columbia University. He takes an unpopular position. Victoria Nuland (American diplomat. Since September 2013 Undersecretary of State in the service of the American Department of State and responsible for Europe and Eurasia) also teaches at the same university with positions opposed to those of Sachs. If there is no evidence of some "bribed" status of Sachs, we must assume that he expresses his views without any connection to Moscow.

By the way, we should assume mutatis mutandis with Fukuyama. We could also disqualify Fukuyama's view on this conflict by saying that he is simply parroting the positions of Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, or the CIA, which, in Sachs's opinion, is behind the Maidan revolution 2014 that overthrew the predecessor of Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

If we do that, then any unbiased discussion becomes impossible. So even if Sachs' positions could also be found with Putin, that is irrelevant just as it is irrelevant for an assessment of Fukuyama's position if it turns out that he says something that Biden or Harris said.

This is crucial to understand because we, the whole world in fact, are on the eve of a meaningful discussion about whether we should continue to support Ukraine in continuing a war with Russia. This discussion must be conducted in an honest manner. It should not be the case that two parties accuse each other of one parroting the other party. Argue pure and factual.

When Fukuyama gets to the point

After Fukuyama launched his disqualification, he developed more businesslike arguments: “Sachs is not realistic about the threat we are facing”. Fukuyama thinks that Putin wants much more than just Ukraine. He wants Moldova, the Baltic states, and perhaps more.

Fukuyama continued: “The threat from Russia is not going to cease,” and Europeans will, therefore, have to spend more on defense. Fukuyama suggests 5% of their gross national product, instead of the 2% that NATO currently prescribes.

Pierce Morgan then confronts Fukuyama with his old views from his book “The end of history...” and the prevalence of liberalism. Does he still think that way? Fukuyama answers that he does. For example, he does not see China proposing a viable alternative to American liberalism in the next 50 years.

In other words, liberalism remains Fukuyama's dominant model. Thirty-five years after its publication, Fukuyama's only self-reflection on his theory is that he could not have foreseen the extent to which liberalism, in the sense he defines it, would be rejected in the United States of America itself.

But he does not elaborate on the nature of that rejection. I fear that he is referring to what we call “the far right” whereby Fukuyama continues to think within the familiar politically correct frameworks of the European globalists.

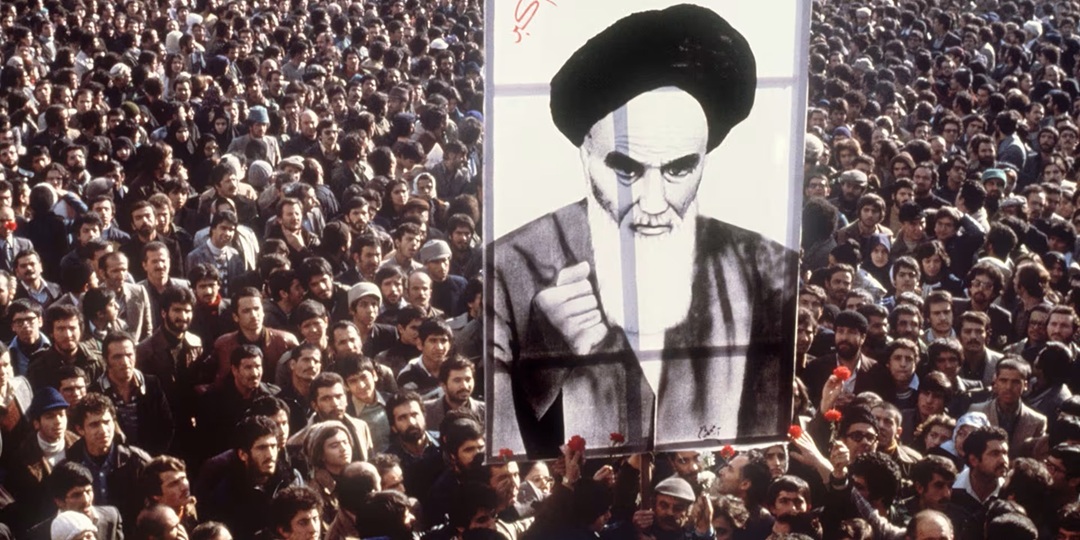

He still has a blind spot for the challenge of Islamism (political Islam). He already had that blind spot in 1989 when he talked about some “crackpot messiah” who might still make some noise but who would not fundamentally influence the course of history.

This showed that Fukuyama had a blind spot for religion and a blind spot for the mobilising power of political Islam. In the 35 years that have passed since 1989 (the Rushdie affair, Mohammed cartoons, Islamic State or the knife attacks inspired by radical Islam) Fukuyama should have been open to the weak point of his “end of history” thesis.

But they were not. Nor did Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations thesis (much more realistic than Fukuyama’s work) from 1993 lead Fukuyama to the insight that many factors and actors at work in this world pose a serious challenge to liberalism.

But back to the Sachs-Fukuyama contrast on Ukraine. Sachs claims that Russia does not fundamentally challenge “the West”. Sachs thinks that Russia is only concerned with Ukraine. Fukuyama expresses the more familiar voice in Europe that Putin is concerned with much more than he is a danger to the whole of Europe.

It is difficult to say which position is correct in this regard. Both sides rely on evidence, and both positions involve speculation about Putin’s motives. Fukuyama does not provide any verifiable argument as to why he attributes these imperialist ambitions to Putin, so that discussion needs to start.

That is precisely why it is so essential that we conduct this discussion on business grounds.

Only one worthwhile sentence in the whole article. The last sentence.

This is classic Globalist Article. Classic.

Debating the fake targets.

Those two from Columbia take opposing views of stuff that is only a distraction.

And they ARE both paid to do it;

waisting people’s time,

which is what this article is.

But I grateful to be able to respond,

thank you.

Now will you?

Here is what you should be debating or discussing:

FORECLOSURE

EVICTION

OCCUPATION

CONQUER (from within)

The oldest strategy known to man since the conjuring up of money.

Personally I am not anti-capitalism nor anti money.

You know better Arthur Blok. Why do you publish this kind of stuff? I know.

Because you want conflict: arguments.

Great!

Try arguing with me. I invite you.

🌅🙏🏽💜 Angel NicGillicuddy

“Buffer State”

The latest fake news globalist

buzz word.

A Neutral State,

which would end up like Gaza.

No way.

💜 The Abraham Accords

Not good timing.

Columbia University is in

big trouble right now.

Sanctuaries will go completely broke

when demurrage (holding charges)

is declared on The US DOLLAR.

Their only power is

PAPER US DOLLARS.

💵💵💵💵💵💵💵

Same for The War in Ukraine.

Same for Gaza.

But first let’s flush out as much as possible

for a successful economic launch,

so that all the hidden 💵💵💵💵💵

will have a good place to go.

Even the oligarchs will like it.

The Trump Gold Card.

Soon it will be brinkmate for them.

But that’s better than losing.

The Caravan business

is already coming apart.

It is certainly a blunder that Fukuyama doesn’t incorporate the other obvious threats to politically correct globalist liberalism. This sets him apart from a serious discussion. Islamism is such an obvious threat.—Another lapse in his thinking is that Putin’s Russia doesn’t have an ideology to deliver. Russia today lacks a coherent ideology—at best Putin seeks to restore a pre-communist Russia. This doesn’t demand a world hegemony.