Through a series of fortuitous coincidences, I got a chance to watch a BBC adaptation of Kafka’s The Trial (1993) and rewatch an old favourite of mine, Terry Gilliam’s mind-bending dystopian sci-fi epic Brazil (1985). I’ve always believed that SF, no matter how good or big it gets, needs to return to its fantasy roots occasionally—surrealism and magic realism included.

By Emad Aysha

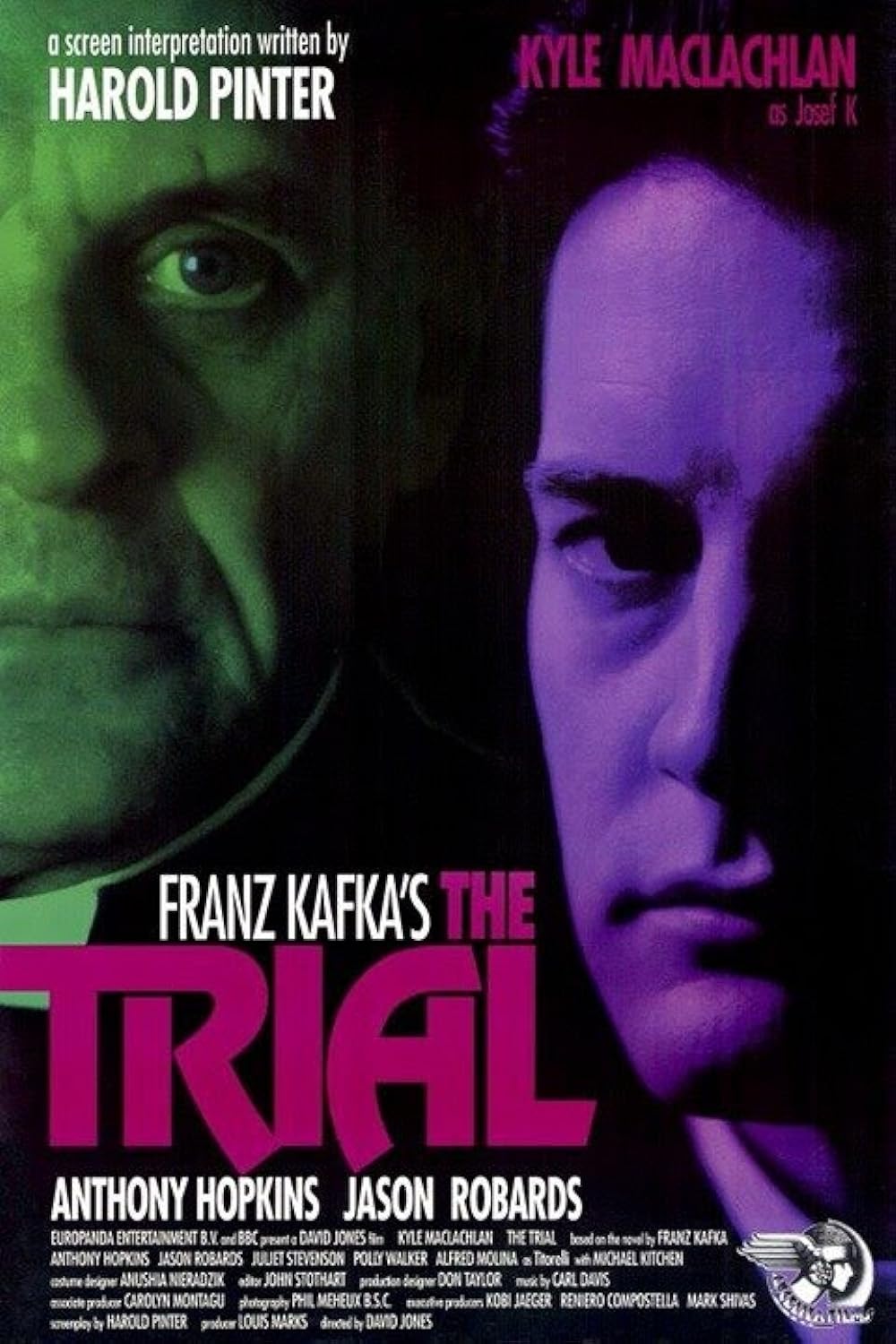

In this case, however, I’d say Gilliam was one step ahead of the BBC production. That’s no fault on Kafka's part since the producers couldn’t create the proper sense of unreality called for, which is most definitely contained in the original classic novel. Watching the Trial was quite tricky for me for personal reasons.

Given the vagaries of life in the Middle East, you could ‘relate’ to it all too much. All the relics of modernity – courts, records, formal procedures – are without any substantive.

Joseph K. (Kyle MacLachlan) wakes up one day to find he’s under arrest by cops who won’t identify themselves for a crime that nobody will inform him of – they don’t know themselves. His relations try to help, but K’s insistence that he is living in a modern country with written rules and set procedures and his refusal to cooperate gets him killed in the end.

I was particularly freaked out by the scene where his erstwhile lawyer ignores another miserable client who practically must beg and kiss the man’s hand to have his verdict postponed indefinitely. Insult your penny, not yourself, as the Egyptian saying goes.

Stringing him along is precisely what the lawyer wants, with his life on hold. Even the lawyer’s home/office is decorated in a dusty, flowery way that reminds you of places I’ve been to here in Egypt. The same goes for the court building and the older parts of town.

There’s another cute scene where K. meets an artist who works for the courts (everybody seems to work for the courts in this crooked world). The man tells him a genuine acquittal is near impossible, and postponement is the only realistic option. Again, this is quite an apt reality in this part of the world.

Women and connections and massaging people’s egos are the only way out, not due process. Surrealism is hyperrealism, showing you the ugly reality hiding behind the scenes or, more likely, in plain view. A reality within a reality.

The only catch with the 1993 film is that it takes itself too seriously, functioning like a period drama concerned with historical and even technological accuracy, denting the sense of unrealism. The music isn’t weird enough, either. Only the performances, especially by Anthony Hopkins and Alfred Molina, save the day. But that’s still not an excuse.

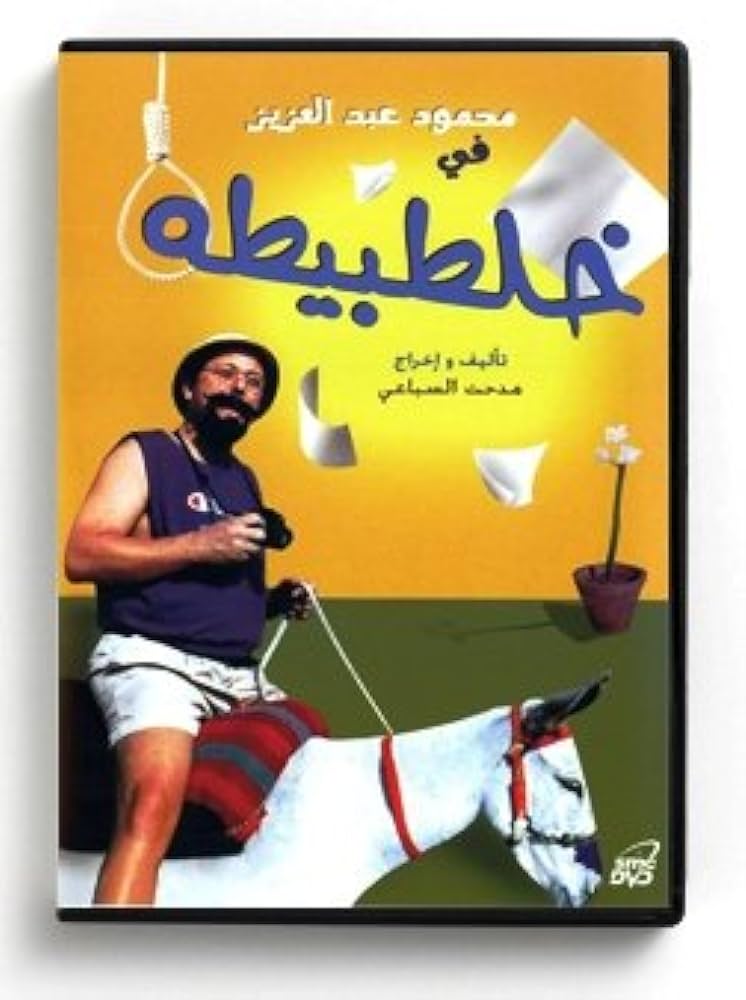

There’s an Egyptian movie by Mahmoud Abdel Aziz, which I’m sure is an adaptation of The Trial. It's a humdrum production but does a better job because of its reliance on humour. The movie is capped off with a reasonably happy ending, which brings me back to Brazil.

In Terry Gilliam’s Orwellian nightmare world, you have a bureaucratically mad England, with quite a lot of Americans and people with foreign accents, where a lowly bureaucrat in the Ministry of Information named Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce) is having dreams of soaring through the air and rescuing his sweetheart like a knight in shining armour.

He encounters the girl of his dreams in real life, Jill Layton (Kim Greist), while sorting out a case of mistaken identity—a hapless citizen named Buttle who gets misidentified as a ‘subversive’ freelance repairman named Tuttle (Robert De Niro).

Jill gets mixed up in this case, too, because she’s filing a wrongful arrest form, forcing her to go to several dislocated ministries to get stamps and forms, and so threatening the interrogator in charge – Jack Lint (Michael Palin) – who killed Buttle by accident. (The MOI now owes the Buttle family a ‘refund’; those interrogated are called customers).

NO ESCAPE: Modernity is out to get you when you least expect it, and the BBC is the best way to tell you about it!

Lowry has Jill deleted from the data banks and almost gets away with it, but the police capture him and accuse him of a series of bureaucratic mishaps he wasn’t responsible for. That includes sabotaging his heating system – Tuttle fixed it for him, and Central Services accuse Lowry of being a terrorist.

The surrealism of the movie, apart from the ugly/crazy reality of it all, comes mainly from Lowry’s dream sequences where he battles to rescue Jill, with those dreams catching up with him even when he’s awake. His guilty conscience is tormented by what happened to Buttle’s family and the escapist desire to get away from it all, from this buying off of people’s freedom and personal integrity through creature comforts and shopping sprees.

In the penultimate scene, when he’s being tortured by his friend ‘Lint’, he gets rescued by a guerilla fighter, Tuttle and even finds Jill again, only for us to realise that it was all a dream. He withdrew into himself, under the torture, to get away from it all. He finally found his freedom in the one place where his original prison was located – himself.

The scene in the shopping mall where he’s fighting with Jill next to a mirror makes it look like he’s wrestling with himself. The same is true in his dream sequence up against the giant Samurai warrior. (For more details, please watch the Criterion Retrospective on Brazil.)

The advantage of science fiction is that you can create any world you like to fit your themes, making the unreal real. The only catch is that you still have to ground this world in the laws of nature; fantasy is more flexible, and surrealism is more harrowing. But in the wrong hands, surrealism becomes too stiff, and in the right hands, SF—and comedy—can do the trick.

TRANSLATED REALITIES: 'Khaltabita', the Mahmoud Abdel Aziz movie adaptation of 'The Trial'.

My God, do we need Kafka in this part of the world? It’s too real to bear anymore!