A remarkable discovery over the reading and the influence of Lebanese poet, writer, and artist Kahlil Gibran by the style of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. Reading Nietzsche's posthumous essay “On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense” (1969) in “Le livre du philosophe” (Aubier Flammarion, 1969_ triggered this new finding: “Are we all trapped in a bubble.”

By Eddy Choueiry

The main statement of Nietzsche’s manuscript says that we are trapped in a bubble that prevents us from reaching the Essence of things.

Science can only lead us to illusions and should be under control. Art is also an illusion that flirts with reality. But art doesn’t cheat because we know it’s an illusion, so it’s true.

The fable that caught my attention in the first few lines is very important.

After reading these few lines, I was reminded of a story by Kahlil Gibran. This story can be found in his first book written in English, titled “The Madman” 1918, and it’s the remarkable fable of “The Three Ants.”

Nietzsche’s most famous book, “Thus Spoke Zarathustra,” profoundly influenced Gibran in 1883. But did he read “On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense”?

Could it have inspired him to write “The Three Ants”? Studies focusing on Nietzsche and Gibran have been relatively scarce.

I found an interesting paper written by German Professor Stefan Wild, former director of the Orient Institut in Beirut, in December 1969 for the Quarterly Journal of the American University of Beirut, “Friedrich Nietzsche and Gibran Kahlil Gibran.”

Joseph Geagea, the Gibran museum’s director, sent me an attractive study on Gibran and Nietzsche written by Rasha Ismaiel Al-Kinani in “Between Nietzsche’s Hammer and Gibran’s Shovel,” LARQ Journal of Philosophy, Linguistics, and Social Sciences Vol. (4) No. (43) year (2021). However, these two studies do not mention any other books of Nietzsche read by Gibran.

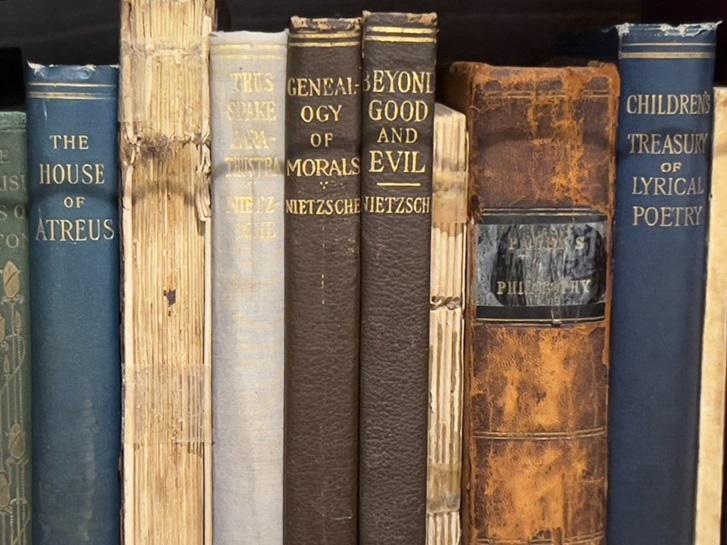

After contacting Sophia Denkova Delcheva (a specialist in preserving Gibran’s archive and artworks) to delve deeper into this topic, she informed me that Gibran owned five books by Nietzsche, including two editions of “Thus Spoke Zarathustra,” “Beyond Good and Evil,” “The Genealogy of Morals,” and a special edition of “The Life of Friedrich Nietzsche” dedicated to Gibran by Mary Haskell in 1913.

Soon after, I had the opportunity to visit the Gibran’s Museum in Bchareh with the kind assistance of the director, Joseph Geagea.

Together, we commenced our investigation.

Sophia carefully examined Gibran’s extensive collection of books, hoping to find any trace of Nietzsche’s essay. Meticulously, we inspected every page of the five books, looking for any annotations or indications that Gibran may have engaged with the text.

Employing ultraviolet light, Sophia skilfully detected fingerprints within the books, proving that Gibran had handled them. The worn-out spines of the books further hinted at their frequent use.

Gibran had not come across the specific Nietzsche essay I was searching for. As a result, some may consider it a flaw that “The Prophet” was inspired by “Zarathustra.”

Explaining the profound connection between Gibran’s and Nietzsche’s two fables becomes intriguing.

These two distinct narratives harmonize remarkably, offering parallel insights into the human condition. Both tales eloquently unveil the illusion and confusion that often beset human beings.

I attempted to intertwine the two fables to show that their meanings remain unchanged.

For a minute, “The World History” witnesses the arrogance and duplicity of these “clever animals” on a narrow understanding called Science. Nevertheless, it was only a moment, then Nature, by a few careless breaths during its slumber, swiftly crushed these ignorant ants.

It is plausible to assume that the “clever animals” in Nietzsche’s fable correspond to the hard-working ants depicted in Gibran’s narrative. The prideful “clever animals” who claim knowledge align with the third ant in Gibran’s fable, who pretends knowledge of the exact situation.

It is truly remarkable how Gibran elucidates and concurs with an identical perspective without having read Nietzsche's fable. Both fables convey the notion that human beings, akin to the third ant, may come close to grasping the intricacies of the human condition yet ultimately fall short of comprehending the Essence of their existence.

Despite Gibran’s admiration for the Nietzschean style, he maintained a unique perspective that diverged from Nietzsche’s nihilistic philosophy.

In conclusion, this humble quest was unveiled for the first time, specifically Nietzsche's books, which were owned and used by Gibran. Regardless of Gibran’s opposition to Nietzsche’s nihilism, these two fables undeniably form an exception, showcasing the striking similarities in their messages of the human condition, independently from any previous Nietzsche direct reference.

The absolute reference for Gibran was “Thus Spoke Zarathustra”; in fact, we discovered that he had two copies of it: A very used copy with Gibran annotations and a second new copy almost untouched.

In Ecce Homo, Nietzsche wrote, “In my lifework, Zarathustra holds a place apart. With it, I gave my fellow men the greatest gift ever bestowed upon them. ...Such things (his words) can reach only the most elect; it is a rare privilege to be a listener here; not everyone who likes can have ears to hear Zarathustra”.

In “The complete works of Friedrich Nietzsche,” volume 17, edited by Dr.Oscar Levy, “Ecce Homo” New York Macmillan Company, 1911.

Thus, Spoke Zarathustra is a book for All and None. As a poet and artist, Gibran is the elected one who can perfectly resonate with his colleague Nietzsche.

Eddy Choueiry is a Lebanese scholar who has worked on researching Lebanese heritage and promoting the richness of its legacy. He has written various books and published articles on Lebanese agricultural, architectural, touristic, maritime, and cultural heritage. This is his first contribution to The Liberum.