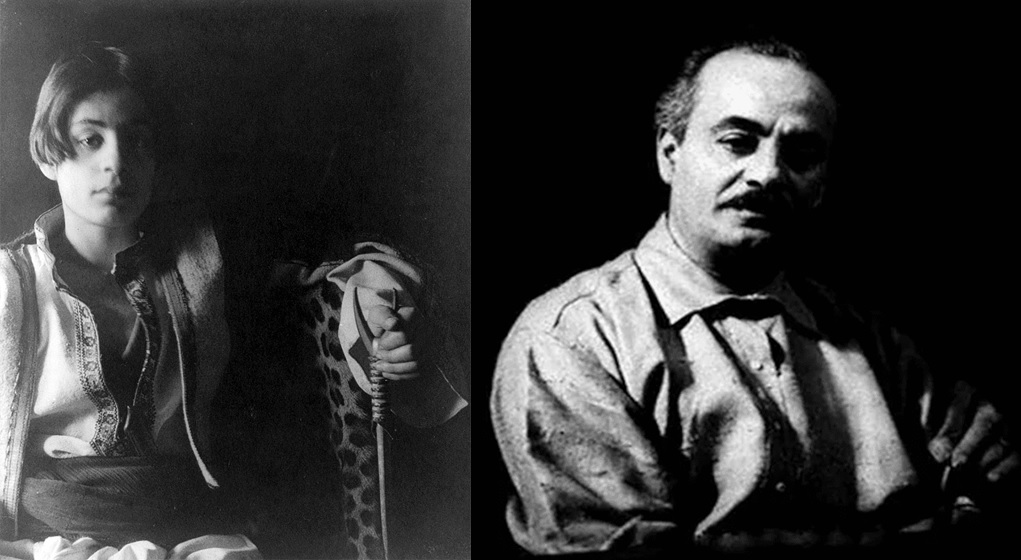

There was an interesting Zoom conference on Lebanese poet, writer and artist Khalil Gibran, where a contemporary translation of The Prophet by poet Henri Zugheib was the main topic. As a translator, I was intrigued; Zugheib wanted a more relaxed text that younger generations could handle, explaining that all translations are probabilistic approximations, so there’s always room for new translations.

By Emad Aysha

Keeping the old text relevant to new times is almost a duty. The important thing, he insisted, is being true to the spirit of the text. The content is more than the form. That includes Arabic cultural and language norms. One example he gave was the term 'hand' of God. This is too literal a translation since it’s palm since the hand extends to the arm in Arabic.

The second example was the word ‘bear’, with the Prophet discussing the ship that would bear him to the island where he was born and the woman that would bear him.

Gibran is creating a parallelism, so again, you can’t translate it literally as delivered in the sense of gave birth to. Every writer has his own lexicon, the invigilator Iklas Francis added, which means that you have to read all his works to understand him, the themes that captivated him, and the phraseology he used.

Gibran was a delicate soul, and all of his writings are from the perspective of his hero in The Prophet. He’s his authentic voice. It also turns out there were many little errors in the older translations from Arabic to English.

All this talk of translations got my mind working on science fiction. Translation is a fundamental dilemma in the genre, almost foundational, since what we’re trying to do in it as authors is communicate future or alien worlds to a human audience caught in the here and now.

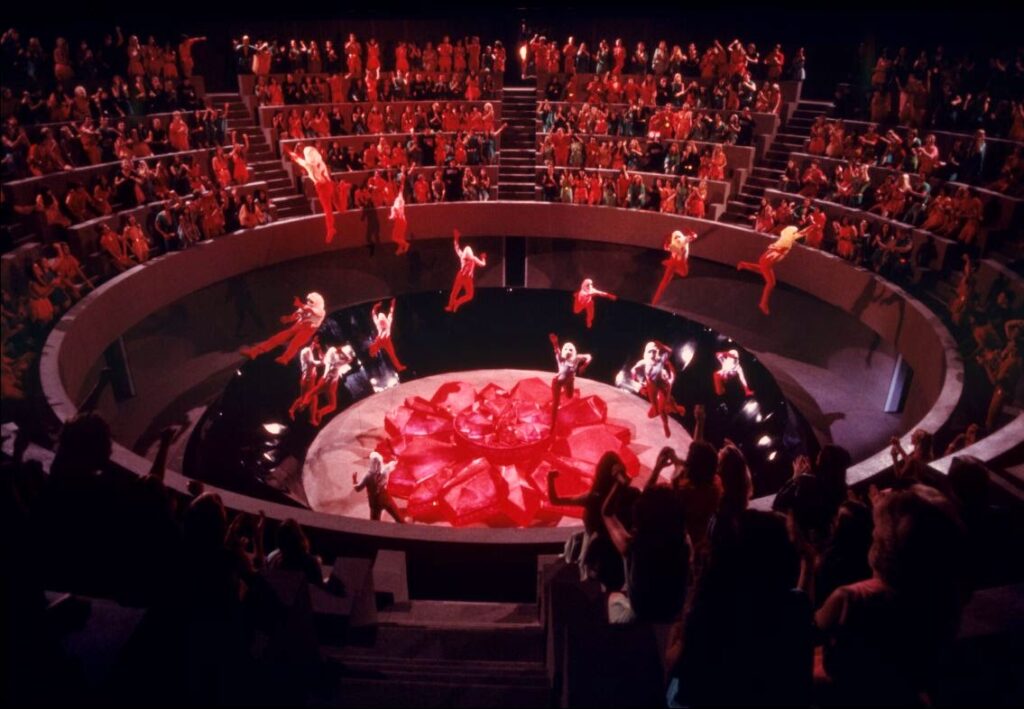

We get around that problem through motifs, symbols and cultural references people can relate to. An excellent example of this is Logan’s Run (1976). I remember certain scenes so vividly as a kid because of the imagery.

DEAD RED: A scene from 'Logun's Run' (1976). Seems colour-coding is another form of translation we can all relate to, whatever culture (or time zone) we belong to.

People aged 30 get zapped in a stadium, like the Coliseum, which calls back gladiatorial contests and people enjoying the death and carnage and condemning fighters to death with the thumbs down. (The same imagery, of course, in The Running Man, with the so-called Stalkers dressed up like professional wrestlers and armed like psychopaths in a slasher movie).

Note the volunteers-to-die are dressed in hooded robes, with skull-like masks and flaming red patterns too, all portending death and how they will be zapped/incinerated. But it also calls back the Inquisition.

You see the same kind of inquisitor-type imagery in Eyes Wide Shut, with the hooded robes and masks, Tom Cruise being held accountable by someone dressed like the Pope, and two elite guards standing on either side of the man.

Suppose you return to the original 1967 novel by William F. Nolan & George Clayton Johnson. In that case, you find cultural references there, too, such as the Guns used by the Sandmen to hunt down those who refuse to die at the allotted age – compared to six shooters from the Wild West and callbacks to bounty hunters. Sandmen is a fairytale reference; the Sandman in American lore ‘puts you to sleep’.

I’d say the movie did a better job out of necessity. It had to use visual signifiers as a shorthand because it couldn’t do all the narrative exposition that you have in the novel. The movie is also more compact since it all happens in a single city, whereas the entire world is run in this dystopian manner in the book.

The city, or city-state, is the classic motif of motifs from the Western world at least. Perfect for narrative and thematic focus, miniaturising the task of world-building to the benefit of both writer and reader.

In the original Planet of the Apes movie, the entire ape planet, with its modern technology, was summarised into a single ape city with a simple pre-industrial mode of life, for budgetary constraints, that worked wonders nonetheless on the silver screen.

Science fiction, then, is a form of translation all its own.

You can see these theme-to-symbol considerations in Gibran’s The Prophet, with the hero referred to indirectly as The Mustafa (or Chosen One), an Islamic reference. The whole title, The Prophet, is very Islamic sounding, and the conception of religion that the hero preaches is holistic, again on an Islamic mould.

At the same time, the questions posed to the prophet by the people about ‘giving’ – Dr. Dorine Nasr raised this term in the conference – are very Christian. I would also suppose the journey home for the hero is a Greek reference to the Odyssey.

That, in turn, would explain the elliptical ending in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 (1968). Bowman is journeying back to the very beginning, the Big Bang, with fetus-like imagery and with that leapfrogging to the dawn of man all over again. (How little has changed in terms of violence and tribalism).

If you look carefully (you need to see it in a cinema), you’ll notice how Bowman, as a very old man, eats his gourmet meal like he’s still in zero-gravity on the Discovery, ‘scooping’ the food with his fork. His habits haven’t changed because he hasn’t been there that long. The passage of time here is an illusion.

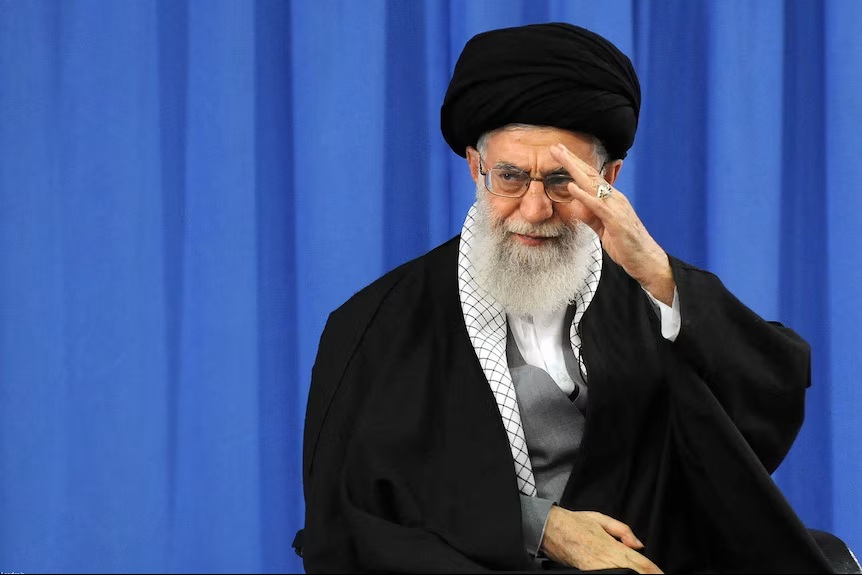

FUTURE SPEAK: I wonder if Kubrick got ideas from Gibran's paintings? They both have a fondness for eyes in the sky!

He becomes the Starchild, a guardian angel trying to keep Earth intact till it’s ready for what lies beyond the monolith. A child, a classic motif of hope for the future.

Henri Zugheib says The Prophet transcends space and time. Translations only become dated, not Gibran’s text—a hopeful messenger to all.

Special thanks to 'Room 19' for letting me sit in on the conversation, and Dr. Faycel Lahmeur for familiarizing me with them!