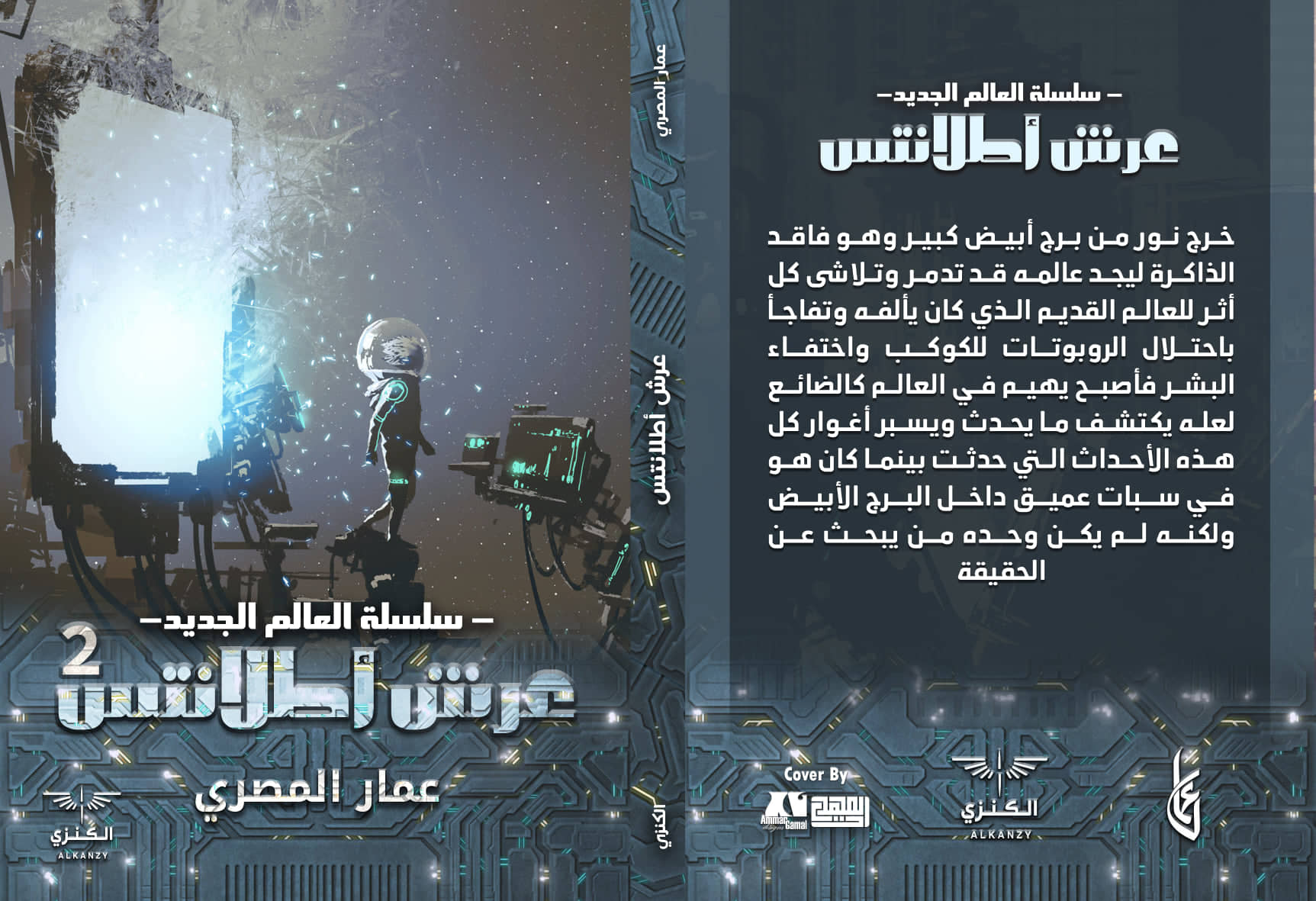

By Emad El-Din Aysha, PhD

What can I say about Ammar Al-Masry’s Throne of Atlantis, the long awaited sequel to Shadows of Atlantis? It’s a mind-boggling treat!

To remind those who have forgotten, myself included, here is a summary. In Shadows of Atlantis you have a near perfect world in the future that is utterly destroyed by an alien invasion. The invaders, however, get the earth-built robots to do the dirty work for them, sending probes in (small metal spheres) that send out a signal that makes the robots rebel against their creators. Robots governed by Isaac Asimov’s laws, to make them perfectly safe and obedient, and robots that were the chief cause for the prosperity of this near perfect world. In the meantime, a select group of humans, who have acquired superpowers, are trained and set against each other inside mysterious towers in preparation for the final confrontation with the robots. Once they exit the towers, they find themselves around the city of New Atlantis, an Egyptian city built close to the archaeological remains of the legendary city of Atlantis. (The language scrawled on those alien metal balls is the same as the language of the ancient buried city. What a spooky coincidence!) It’s the one remaining human city that hasn’t entirely fallen to the robots, thanks to the electromagnetic walls protecting it and the valiant efforts of the Egyptian army.

In the sequel, we have the aftermath with three of our heroes – Ivanov, Ares and Sairi – and a band of kidnapped humans up against the leaders of the alien invasion, or so we think. The remaining heroes with their special abilities are out in the wilderness, being chased by killer robots of varying models and sizes, and arguing philosophy in between breaks.

At the same time there are some human protagonists called the Enix, we saw them in the previous novel, and they seem to serve the same entity, Gladious, who is responsible for the heroes and their new powers. Then you get the really big surprises kicking in which I am unfortunately not allowed to tell you, or else you wouldn’t buy the novel!!

Cons and Pros

The story is difficult to follow given the significantly large number of characters, subplots, plot twists and events. While a little shorter than the previous novel it took longer to read. Throne of Atlantis is positively taxing to your synapses. (Even the human characters suffer towards the end from the stream of revelations). Still, it is a very worthwhile novel and definitely a must read. Say what you want about the storyline but Ammar is a master at ‘pacing’.

I’ve looked at an early draft of Throne of Atlantis so I know how he’s shifted things. The initial draft had too much action and too many revelations very early on in the novel, which desensitises you and also overwhelms you since you haven’t had a chance to absorb what’s going on, the world that things are happening in. Here he paces things out with a small intro sequence and a slowly escalating level of violence and action, interspersed with characters meetings and talking and comparing experiences and impressions. About halfway through the novel, after you’ve had a chance to take it all in and without being bored, you get the heavy duty action, as well as continuation of the humour from before, and then the really big revelations begin to kick in, something you’ve been craving since the action got your appetite going. (You want to know, need to know, why all this is happening; why we should care and sympathise about these characters and all they’re enduring).

Another plus sign in all this is the distinctively Egyptian quality of the story. You see this in the humour, in the sensitivity of several characters, and the philosophical debates. Not to forget the politics, of course!

Nour, the first person we see in Shadows of Atlantis, keeps making weapons out of his imagination while up against an assortment of robots, and the weapons never seem to do any good. At one point in the story he says, I wish that once this accursed power I’ve been given can do something useful. Later, after he loses his friend Jean, to the "Enix" amazingly enough, he bursts into tears and almost kills himself. An American superhero type wouldn’t have felt such recriminations, placing all of the blame on the bad guys, not himself. (Ammar is a sweet and gentle person himself and does not like militarism, or excessive training). In Nour’s discussions with Jean, and also with Keno, you discover both the value and the downside to being human. The robots, for all their faults, aspire to be human. They want consciousness, they want freedom, and beyond that they want emotions and a sense of conscience. The whole reason they are exterminating mankind is that they feel they are better, more human in effect, because of their superior rational and scientific investigative faculties. (This is reminiscent of Isaac Asimov’s story “That Thou Art Mindful of Him” and the more benign novel Robots of Dawn and the whole Giskard and Daneel duo). Later Keno and Nour befriend a robot that helps them and he spins them a tale about how the robot kingdom, after the rebellion, split into two factions. Those that thought they were superior to humans, and those who want to develop emotions and have only succeeded in imitating them superficially, by smiling and other things!

At the same time Nour is angry at being human because it involves betrayal, noting how robots at the very least can’t lie and aren’t driven by jealousy and greed. This hooks into the politics of the story. You learn that the planet the invasion came from, Atlantis, had actually been split in two, after Gaia overthrow his brother the king, Athenos. (The ancient city of Atlantis on earth was a location where this alien race had landed, during their early exploratory missions). Gaia was envious of his brother, thinking himself more worthy. In point of fact, even their father thought of him as more worthy, saying that he was chivalrous and brave, but the people preferred his brother so he didn’t get his chance at the top spot. (He’s also driven by religious zeal, after reading the scriptures and its promise of immortality – much like George W. Bush!)

Gaia uses a secret device his father gives him, which controls the robots, and Gaia uses it to cause a rebellion, forcing Athenos to leave with much of the population, heading towards earth. Athenos contacted the leaders of earth and convinced them to make journeys to Atlantis, which explained the failed space missions in the previous novel and the secrecy surrounding their doomed fates. (That’s what gets Nour angry against the human race, along with what happened to Jean. His disdain for the world’s leaders and their warlike tendencies is why he wanted to join the latest space mission in the previous novel, with his friend Yussef). You can see Gaia is up to no good when he ‘praises’ his brother for taking the throne. The narrative voice tells you he is being a hypocrite, telling his brother what he wants to hear. This is very recognisable to us as Arabs, along with the jealousy he feels towards his brother and how his father is inadvertently feeding this anger.

Gaia is also a mad dictator we’re all too familiar with as Arabs. He slaughters his own people and replaces them with robots, which is why the robots in the previous novel were all imitating human beings, with families, along with doing hideous experiments on people. Gaia wants his new programmable population to be like his people, even looking like them, but totally obedient and physically and mentally superior. There’s an important twist here since Gaia’s capital city is meant to be a Utopia. It’s certainly a beautiful city and the human heroes are impressed themselves on their way out of it, with all those annoying robots in pursuit. (The planet of Atlantis is also charmed, with a crystal ball that generates energy for the robots and makes the planet itself better, including the ‘fruits’. That’s a very Arabic measure of the good life and Utopia, and there are lots of beautiful trees and animals all over the planet).

Another political angle deals with the human city of New Atlantis. Ares, when he gets back, discovers that the human leaders have also lied and are in hiding, in a bunker, like cowards. Ares original mission, from the first novel, is to find a secret weapons system being developed by the Egyptians. Ares was originally working for the Europeans in some unnamed war between the West and the Islamic Union. Fortunately here human solidarity reigns supreme, and it’s these secret weapons that almost save the day. (Gaia is angry at the European, Asian and Russian cooperating against him. He asks them to join his superior race and they politely refuse, knowing that he can’t be trusted having sacrificed his own people).

Gaia is also a stand-in for the Israelis, because he steals other people’s histories, with an elite group of robot soldiers modelled on Pharaoh and other ancient warriors. The heroes themselves comment on this, which makes them all the more determined to fight back whatever the odds. There are other hints about the Arab-Israeli conflict here, since Gaia’s describes his robotic troops as the undefeatable army, (الجيش الذي لا يقهر), something the Israelis said about themselves – before the October war, that is. Not to mention that the planet Atlantis has a Western continent and an Eastern continent, with a giant bridge connecting them and the evil army of Gaia.

Why would you need a ‘bridge’ this far in the future in an advanced alien world where everybody flies around? It’s a symbol for cultural connectedness, in this case between East and West (or North), and how the West is abusing this connection and using it for conquest – on the model of cultural imperialism or globalisation. And it’s on that bridge that Galdious and the Enix will make their presence felt, with their own machinations, driving nations against each other, much like the American superpower or the (presumed) Masonic conspiracy.

The Sci-Fi Interface

Something else worth investigating here is the ‘genre’ this novel belongs to. I remember hearing Ammar Al-Masry say once that he insisted that his sequel be strictly in the sci-fi genre. Shadows of Atlantis has strong fantasy elements in it since you don’t know how the heroes acquired their powers and the training sessions in the towers has a very sorcerer’s apprentice quality to them.

Well, for what it’s worth, it seems that Ammar’s Arabic cultural heritage got the better of him here too, something I am quite pleased with if I do say so myself!

Scientific explanations are given for the powers of the heroes, they hold discussions amongst themselves on the topic, pitching different plausible ideas. Later you discover that they were genetically altered to gain these powers by Gladious, for whatever reason. (You’re kept in the dark about it till the very end, literally). Nonetheless, there is an unmistakable magical feel to the text. The crystal ball that powers the robots and much of the planet was brought to the people of Atlantis by an oracle (العرافة), after all, and the arrogance that comes with too much technological power is unmistakable. The oracle herself belongs to some ancient race, the Lounix, that represent the power of goodness and wisdom and growth in the universe. Opposed to them are the Zorix. Cosmic forces of good and evil in my book. (The wisdom of ages is a theme, evidenced by the fact that Gaia’s own father, elder that he is, confesses to not checking their holy scriptures because he’s not into reading. Gaia films the whole conversation, a hint at the visual obsession of young people in the age of spycams, if you ask me!)

It’s always good to mix fantasy and myths and legends with SF. There’s no telling what might result in the end. The focus of fantasy is different and SF can get too bogged down in the technological and social details of world-building and forget the moral purpose of the story, not to forget the humanity of the characters. Fantasy is older than SF since legends long predate science, but they contain in them truths that have stood the test of time and can inform sci-fi all the better. Not to mention that fantasy writing can feed the format of a storyline, expanding the set of symbols and motifs at your disposal.

One of the nicest anthologies I’ve ever read is Great Tales of Fantasy and Science Fiction Publication (1991), edited by Edward L. Ferman. And one of its most endearing qualities is that it questioned the boundaries between SF and fantasy to begin with, not to mention what was most important to us as human beings – love, happiness, morality, a sense of worth, a sense of mystery. You can see this most clearly in stories like: “The Vanishing American” by Charles Beaumont, “The Accountant” by Robert Sheckley, “Please Stand By” by Ron Goulart, “Jeffty Is Five” by Harlan Ellison, “One Ordinary Day, with Peanuts” by Shirley Jackson, “The Ballad of the Flexible Bullet” by Stephen King, “That Hell-Bound Train” by Robert Bloch and “Not Long Before the End” by Larry Niven.

I bought my copy of Great Tales in Oman, if you can believe it. And at a shop next to a petrol station. If SF and fantasy has penetrated that far into the Arab psyche then there’s hope for us all!!