“Serbia is a country ‘in-between’. It is a place where the future happens first, with all its horrors and beauties,” said the world’s most famous “inconvenient dissident”, Julian Assange, in April 2014.

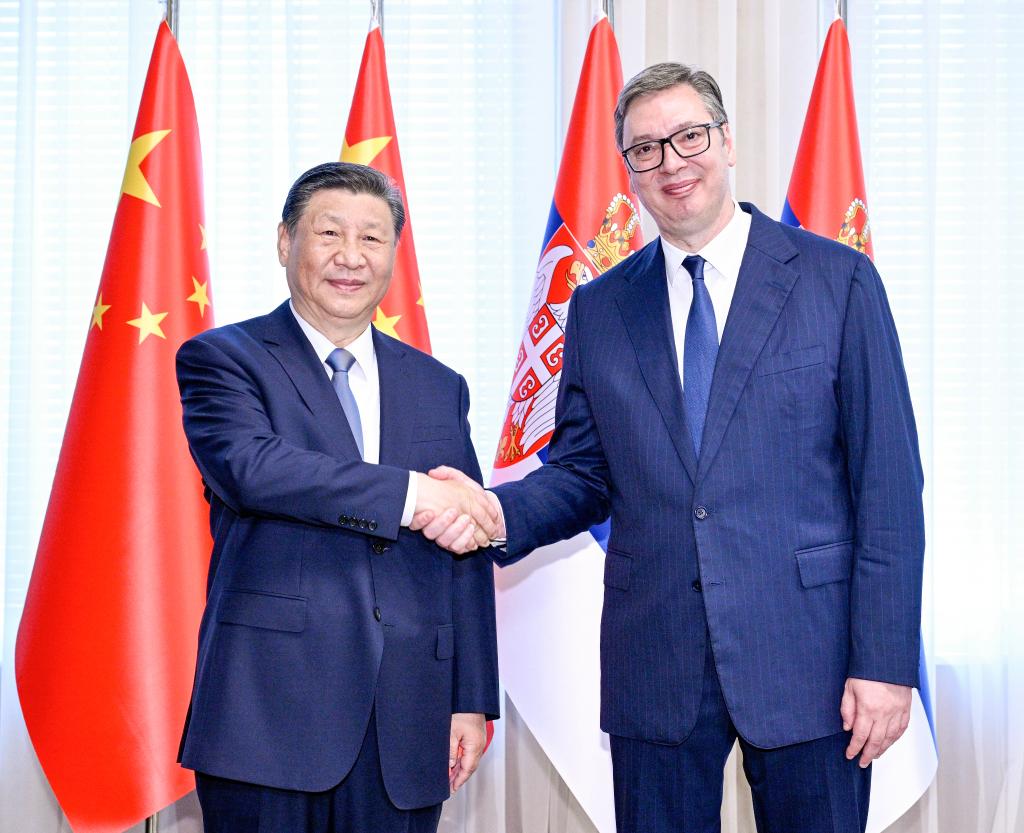

China is widely seen as “the country of the future.” Analysing China’s actions in Serbia shows that the WikiLeaks founder might have been right. It's no surprise that the red carpet was rolled out in Belgrade earlier this month for China’s president, Xi Jinping.

By Nikola Mikovic

The first bridge built by a Chinese company in Europe was in Serbia. The first highway built by a Chinese company in Europe was in Serbia—all during the COVID-19 pandemic. The southeastern European nation was the first country in Europe to approve and start using the Chinese-produced Sinopharm vaccine.

In a significant geopolitical move, Serbia became China's first comprehensive strategic partner in Central and Eastern Europe in 2016. This landmark partnership marked a new era in the region's dynamics, with the Balkan state becoming the first European country to order Chinese-made trains and purchase Chinese-made FK-3 air defence systems.

Serbia is the first Eastern and Central European country to abolish visas entirely for Chinese travellers. In addition, it is the first European nation to sign an ‘agreement to build a shared future’ with China.

Undoubtedly, Serbia's role in the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is pioneering. This ambitious project, launched in 2013 by Chinese President Xi Jinping, aims to expand Beijing’s strategic influence globally by reconstructing the ancient Silk Road trading routes. While the initiative is facing a decline in enthusiasm in most European countries, Serbia stands out as a beacon of interest and commitment.

China is heavily involved in reconstructing the Belgrade-Budapest railway, which should become part of the BRI. Once completed, the transportation route will link Serbia and Hungary, as well as Hungary and Greece—where the Chinese group COSCO Shipping owns two-thirds of the port of authority of Piraeus—via Serbia and North Macedonia.

Critics in the West, however, say that Serbia could serve as Beijing’s “Trojan horse and gateway to Europe.” Some German media reportedly go that far to portray Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic as a “Chinese vassal.” Such rhetoric was not used when the German Chancellor Olaf Scholz recently travelled to China to meet with Xi Jinping. In their view, Germany can develop economic ties with China, but Serbia cannot. Quod licet Iovi, non licet bovi.

However, the fact that Xi visited Serbia on May 7-8 and his delegation signed almost 30 various agreements with Serbian officials perfectly illustrates that the West tacitly approves of Serbia's “ironclad friendship” with China.

One should look at the map to understand Serbia’s position in the international arena. The country is surrounded by NATO and EU members. Unlike China, the West has the most decisive influence in the landlocked Balkan nation. However, as the significant foreign power operating in the Balkans, the United States seems to have “delegated” some of its authority to Beijing.

For instance, in 2016, the Chinese Hesteel Group purchased the Smederevo steel mill previously owned by the American company US Steel. Beijing also owns copper-gold assets in the Serbian town of Bor, which the Chinese Zijin Mining company bought from the American Freeport McMoran Inc. in 2019. But why does the US allow its “major rival” to develop economic ties with a “problematic” country that lies deeply in the Western geopolitical orbit?

In Serbia, China runs mines and factories and builds roads, bridges, and other infrastructure facilities. Politically and culturally, its influence is minimal. That can slightly change, though, if Belgrade implements agreements it has signed with Beijing in media cooperation. Overall, the United States and the European Union are unlikely to allow Serbia to cross certain “red lines” in its relationship with China.

From the European Union’s perspective, until Serbia becomes a full-fledged EU member—which is unlikely to happen anytime soon, if at all—it can enjoy the benefits of the free-trade agreement it signed with China. The problem for Belgrade is that Serbia has very few products that China needs, which is why it may never be able to reduce a widening trade deficit with the People’s Republic.

Politically, the West does not seem to mind Beijing’s declarative support of Serbia’s territorial integrity. Belgrade has de facto given up on its aspirations to preserve at least northern Kosovo under its control, and that is something the US and the EU have been insisting on for decades.

Even if another conflict breaks out in the Balkans (which is not very probable), be it in Kosovo or Bosnia and Herzegovina, it is geography that prevents China from providing direct support to Serbia.

Therefore, the West has no reason to worry about the growing ties between Belgrade and Beijing. Since Serbia will almost certainly stay a country “in-between” for the foreseeable future, its “ironclad friendship” with China—from Western policymakers’ perspective—looks rather benign.