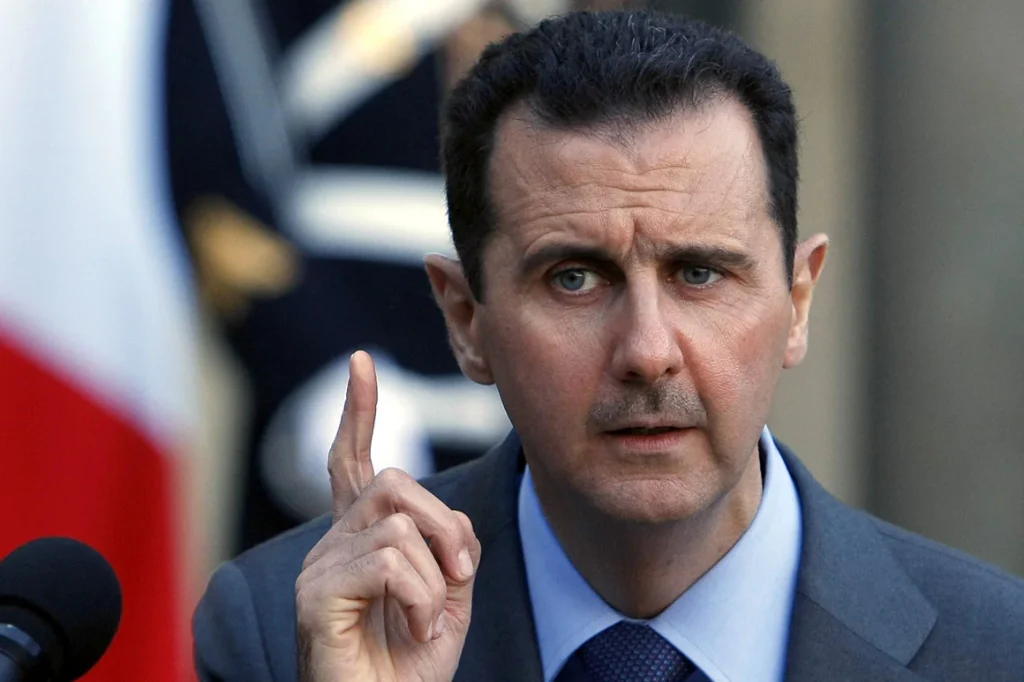

When Bashar al-Assad finally receded from Syria’s political scene, many believed, naively, that the regime’s collapse would usher in the beginning of institutional reform. Instead, power merely migrated from one household to another. Ahmad al-Sharaà has not only inherited Assad’s system but perfected it, emerging as the unrivalled caliph of Bashar, absorbing every instrument of power once monopolised by the Assad dynasty and wielding them with confidence derived from a decade of warlordism. Syria has not escaped the Assad era. It has rebranded its autocracy.

By Rafic Taleb

The machinery of authoritarianism, once built around the Assads, has been seamlessly repurposed for the Sharaà family. The similarities are not coincidental. They are structural.

Where Bashar dictated military promotions, Sharaà now signs the same decrees. Where Asma toured international forums, Latifa Droubi performed the same ceremonial choreography. Where the Assads concentrated wealth, Sharaà’s relatives and in-laws now dominate the spoils of war, reconstruction, and cross-border smuggling.

The hierarchy of communities around power has also been re-engineered, not dismantled. Under Assad, specific Alawite networks—particularly those in the coastal strongholds—enjoyed privileged status. Under Sharaà, an equivalent privileged class emerged among factions aligned with his security bloc and those that consolidated influence after 2016. The same tiered ranking exists, only with new beneficiaries and new gatekeepers.

Even the old Ba’ath Party’s grip on public life has been reconstructed. The former “Regional Command” has been replaced by a “General Secretariat for Political Affairs” that plays an identical role: appointing, dismissing, promoting, disciplining, and surveilling every high-ranking state employee. The faces changed; the function did not.

A Catalogue of Repression, Republished

Sharaà’s administration has revived, refined, and—according to many—brutalised the state’s approach to dissent. The revolution, fragmented and militarised, had once claimed to oppose tyranny. Yet the post-revolution power centres have reproduced the same suffocating logic.

Under Hafiz al-Assad, Hama was crushed as a symbol of state supremacy. Under Sharaà, Suwayda was assaulted with the same cold calculation.

Under Bashar, peaceful protests in 2011 were treated as existential threats. Under Sharaà, demonstrations in Lattakia and Idlib were met with live fire, mass arrests, and systematic intimidation—at least 210 protestors still languish in his prisons, according to local monitors.

Despite presenting himself as a “successor of the revolution,” Sharaà governs with the same playbook: suppress early dissent harshly, criminalise political activity, monopolise decision-making, and delegitimise all alternative civic initiatives as foreign conspiracies or threats to “state stability.”

If Bashar suffocated political life, Sharaà has ensured that no independent political life even begins to form.

The Revolution’s Unintended Consequence

Syria’s revolution initially aimed to topple a dictator and dismantle a suffocating state apparatus. Yet what emerged from its ashes in the northwest was not a participatory democracy or a civic state—but a parallel autocracy, hardened by wartime economics and ideological rigidity.

Instead of pluralism, fiefdoms grew. Instead of accountable governance, armed patronage networks formed. Instead of justice, prisons multiplied—this time under new management.

The “state” that emerged from the fragmentation of revolutionary factions has often displayed the same authoritarian instincts as its predecessor: centralising power, eliminating rivals, censoring critics, and criminalising independent civil society.

In many ways, the revolution unintentionally midwifed the rise of a ruler who learned from Assad not what to avoid, but what to imitate.

Crimes Against Minorities: A Mirror of the Past

While Assad’s decades-long rule was marked by discrimination, siege tactics, and targeted violence, Al-Sharaà’s administration has compounded the suffering of Syria’s most vulnerable communities.

Sharaà’s security branches responded to Suwayda’s protests with arrests, violent dispersals, and a campaign of intimidation unprecedented in the region since 2011. Activists report arbitrary detentions, forced disappearances, and targeted harassment of community leaders.

Christian villages around Jisr al-Shughur and the Orontes valley have faced coercive displacement, confiscation of property, and taxation practices described by rights groups as “sectarian extortion.” Churches have been vandalised, clergy threatened, and historic lands seized under the guise of “wartime jurisdiction.”

Alawite communities in Tartous, Lattakia, Hama and Homs—never fully integrated into the old regime’s inner circle—have suffered under the new one as well. Those who failed to align with Sharaà’s factions were relegated to second-class status, monitored by security bodies, and subjected to suspicion, arrests, indiscriminate violence, and economic marginalisation.

Even Sunni-majority areas—allegedly the revolution’s core—have not been spared. Tribes, activists, and civic figures who criticise corruption or arbitrary governance face swift retaliation. Entire neighbourhoods have been subjected to collective punishment, arbitrary taxation, and weaponised justice.

The new administration did not dismantle sectarian oppression. It redistributed it.

A Dynasty Reborn

The most revealing moment of the past year was Sharaà’s explicit discussion—behind closed doors—of transforming Syria into a hereditary monarchy. What Bashar never dared utter publicly, Sharaà reportedly discussed with confidence:

If Assad’s family monopolised foreign policy, today even senior figures in Sharaà’s own camp do not know what arrangements he makes with Western intelligence services. Diplomats speak privately of a “state within a family within a faction”—a shrinking circle of power, loyalty, and control.

The revolution hoped to bury such politics. Instead, it birthed another man convinced he was destined to rule indefinitely.

A Year Later: The Illusion Exposed

One year after Assad’s departure, the conclusion is unavoidable:

Syria has not escaped authoritarianism; it has replicated it with new architects.

What the revolution promised was never delivered;

What the revolution denounced has been rebuilt;

What Syrians sacrificed for has been betrayed by those claiming to act in their name.

Al-Sharaà today governs not as a transitional leader, not as a reformer, but as the unrivalled caliph of Bashar; continuing the legacy, inheriting the machinery, and enforcing the same suffocating order under a different flag.

The tragedy of Syria is no longer only the endurance of tyranny. It is the realisation that tyranny can survive a revolution. And return wearing its colours.