Article 7(1) of the Dutch Constitution explicitly prohibits state censorship. Nothing can be withdrawn from view, made unavailable for comment, and placed beyond the reach of public reflection in advance. Only after publication can action be taken. Since the Enlightenment, the prohibition of censorship has been widely regarded as a great good and the norm in Europe. That is no longer the case, especially in France.

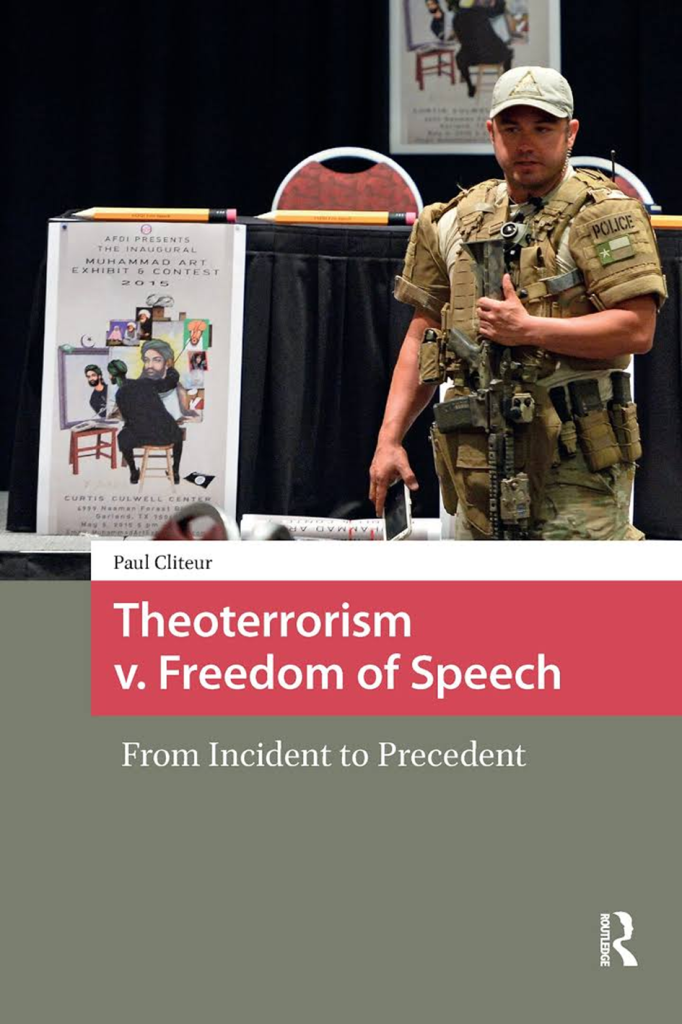

By Paul Cliteur

The best-known instance of censorship in human history is probably the prohibition imposed on Galileo Galilei by the Catholic Church in Rome, which forbade him from publishing his work on the solar system (with the Sun at the centre rather than the Earth).

In 1616, the Roman Catholic Church summoned Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) to Rome. The Congregation of the Index declared the Copernican worldview (that the earth revolves around the sun) “contrary to Scripture.” Galileo was formally instructed that he was not permitted to defend, teach, or publish these ideas as fact, but only as a hypothetical possibility. In 1632, despite the prohibition, Galileo published a book defending the Copernican worldview. A trial followed in 1633, and the Inquisition convicted him.

Responsibility after the fact

That, in short, is censorship. The prohibition on censorship developed against the background of the inalienable right of every human being to access, share, weigh, and debate information. In 1948, Articles 18 (freedom of thought) and 19 (freedom of expression) were incorporated into the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Since 1948, the rejection of prior restraint has served as a guiding principle in all countries committed to liberty.

Although it rejects censorship, Article 7 of the Dutch Constitution does not exclude responsibility after publication. One may be required to account for an expression after the fact, for instance, when something has been published that violates criminal law. Article 137d of the Dutch Criminal Code prohibits incitement to hatred against a group based on that group’s “race.” Whoever violates that prohibition may be convicted. Article 137d thus operates as a limitation on Article 7.

Keeping (prior) censorship and after-the-fact punishment to an absolute minimum

Countries that prioritise freedom in their value hierarchies seek to minimise such legal restrictions. Limitations on press freedom may exist, but they should occur as rarely as possible. And above all, censorship should be excluded to the greatest extent feasible.

Could there be exceptional situations in which censorship nevertheless must be considered? Yes. You cannot allow the internet to host manuals explaining how to make bombs. Nor can you permit child pornography to be published first and only afterwards decide that it must be removed. Still, censorship should be minimal—and so should after-the-fact restrictions on press freedom.

France: once the country of the Enlightenment, now also of the Anti-Enlightenment

For a very long time, the above norm dominated Europe—essentially since the Enlightenment. As Élisabeth Badinter describes in her trilogy Les Passions intellectuelles (I. Désirs de gloire (1735–1751), 1999; II. Exigence de dignité (1751–1762), 2002; III. Volonté de pouvoir (1762–1778), 2007), France led the way in spreading Enlightenment philosophy.

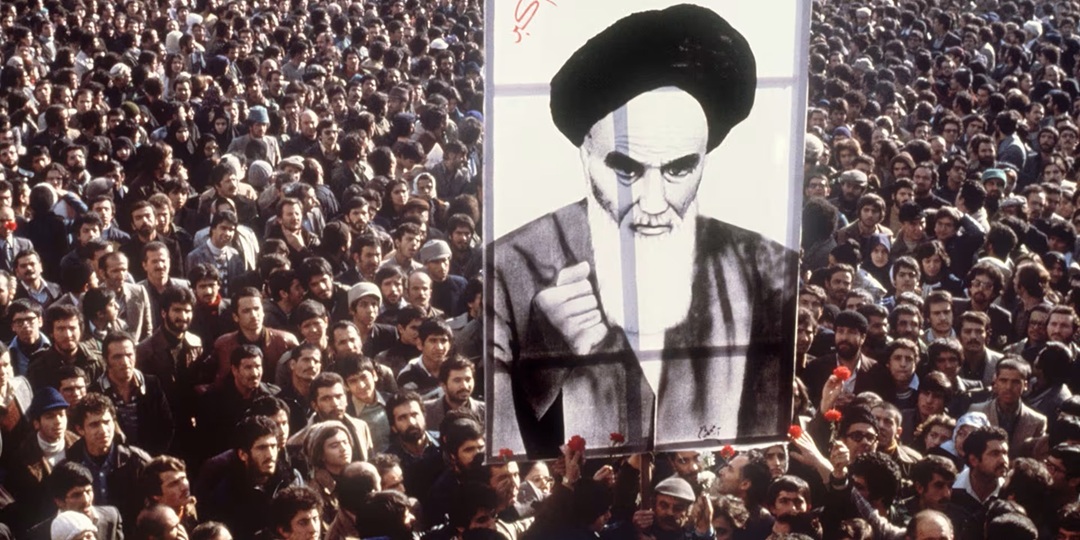

Since the European Union—established on November 1, 1993, by the Maastricht Treaty—came into being, this has no longer been the case. France has fallen under the spell of the Anti-Enlightenment. And that means the defence of ever more restrictions on freedom of expression and even of censorship.

That, too, is possible. A country can orient itself toward the Enlightenment (as France did during the Enlightenment). Still, it can also slide into the Anti-Enlightenment (France today), as becomes clear from Zeev Sternhell’s Les anti-Lumières: Une tradition du XVIIIe siècle à la guerre froide (2010).

The contemporary French philosopher Michel Onfray speaks in Théorie de la dictature (2019) and L’art d’être français: Lettres à de jeunes philosophes (2021) of “L’Empire maastrichtien,” a deliberate allusion to the Third Reich.

The European Commission is in the grip of the Anti-Enlightenment

I will briefly highlight two manifestations of this “Anti-Enlightenment” that have gripped France.

The first is France’s enthusiasm for Thierry Breton’s plans for censorship. That is what it is: censorship. Breton has become widely known following Donald Trump's announcement that he is no longer welcome in the United States and will not be granted a visa. Why? Because Breton is held responsible for the European Digital Services Act, under which X, Elon Musk’s online platform, was fined €120 million. That fine would be due to X’s refusal to comply with the DSA’s standards.

This €120 million fine imposed by the EU on X (formerly Twitter) was the first official sanction announced by the European Commission under the Digital Services Act. The sanction was announced in December 2025 and is regarded as the first non-compliance decision under the DSA since the law became fully applicable.

By imposing this fine, we crossed a historic threshold. But the Americans do not accept that threshold. There is an enormous difference between the American view on free speech—which seeks to keep censorship to a minimum—and the French view that the European Commission has adopted as its guiding principle.

The European Commission seeks to subject online platforms to increasingly stringent censorship. Three themes are invoked constantly: misinformation, disinformation, and incitement to hatred. Platforms are said to bear responsibility for monitoring (i.e., censoring) content to combat these phenomena.

If Breton and the European Commission succeed in “taming” X by forcing it to censor everything that even resembles misinformation, disinformation, or “hate speech,” then the Enlightenment tradition in Europe has come to an end. We will have arrived at the Anti-Enlightenment.

But Trump has now fired back. No visa for Breton. That is good news for friends of freedom. Censors—Breton foremost among them—must also accept the negative consequences of their harmful conduct.

Brigitte Bardot was wrongly convicted

A second example of France’s present-day support for the Anti-Enlightenment (rather than the Enlightenment) became clear upon the death of the former French star Brigitte Bardot on December 28, 2025. In virtually every notice about her, one detail was repeated: Bardot had been convicted five or six times for incitement to hatred and discrimination—primarily for statements about Muslims and immigrants.

In France, “incitation à la haine raciale” (incitement to racial hatred) is a criminal offence, as it is under Article 137d of the Dutch Criminal Code.

How did Bardot see this herself? As I explained in Bardot, Fallaci, Houellebecq, and Wilders (2016), Bardot maintained that her statements fell within the bounds of freedom of expression. She sought to warn against mass migration—especially from countries whose culture she considered incompatible with French culture and, until recently, with Western culture more generally.

But under so-called “anti-racism” legislation, that warning is struck by restrictions that in practice make free debate about migration all but impossible.

One example. In 2008, Bardot was convicted by a French court following an open letter from 2006. In that letter, she denounced the Feast of Sacrifice (Eid al-Adha) and spoke of an “invasion” of Muslims in France.

Why was that criminal? The court held that Bardot crossed a line by using generalised, hostile language about a population group. That amounted to “incitation à la haine raciale.” The result was a €15,000 fine.

Is such a conviction defensible? I would argue that a country in which convictions like that of Bardot’s occur frequently is less free than a country in which they are rare. Likewise, a country with extensive censorship—of the kind Breton seeks to impose on X and other online platforms—is less free than one in which such measures are limited.

Freedom under pressure

Freedom is under pressure—not only from the French judiciary or from the censorship plans of the European Commission and the European Union, but also because people today often rank other values higher than liberty.

Let me elaborate on this. Breton receives support from those who argue as follows: disinformation is dangerous. What is wrong with regulating it? Misinformation is a problem. Why shouldn’t we tackle it? Hate speech is corrosive. Why shouldn’t we restrict it? Freedom of the press is not absolute.

From an Enlightenment perspective—the perspective Badinter defended in her trilogy—these arguments are weak. What is “disinformation”? Disinformation is false information spread deliberately. But to accuse someone of deception and fraud, one must first be able to debate the contested ideas openly. In other words, to demonstrate disinformation, censorship must be bypassed.

The same holds for misinformation. What is it? Misinformation is incorrect information spread accidentally. Galileo’s predecessors spread misinformation about our solar system. They likely did so in good faith—and that is why we do not call it disinformation.

This example illustrates that misinformation is a daily reality in science. Every outdated scientific theory is, in a sense, “misinformation.” But why is it a bad idea to combat misinformation with censorship? Because what counts as “information” and what counts as “misinformation” remains contested among scientists.

Researchers who advance a theory that has fallen out of favour must remain free to try to make it plausible again. Here, too, censorship is ill-advised.

And “hate speech”? Surely that can be prohibited?

Yet here as well, the dangers are considerable. To begin with, there can be profound disagreement over what should be considered “hate” and what should be recognised as a legitimate contribution to public debate. French judges who convicted Bardot for spreading racial hatred (“incitation à la haine raciale”) will characterise Bardot’s statements as hateful. But how did Bardot see it? She would argue that her warnings about mass migration constitute an essential contribution to public debate.

She would also regard her claim that Islam is fundamentally incompatible with French culture as a vital contribution to political discussion—not as the venting of “hate.” The judges who tried to silence her (not easy, given that she was convicted five or six times) are, in Bardot’s view, not fundamentally different from the inquisitors who tried to silence Galileo.

In other words, “cleansing” the internet of “hate speech” is an exceedingly risky enterprise—one that Americans currently understand better than the French. The United States is presently defending the very perspective that Badinter still presented as classically French.

Merci for this detailed, scholarly article.