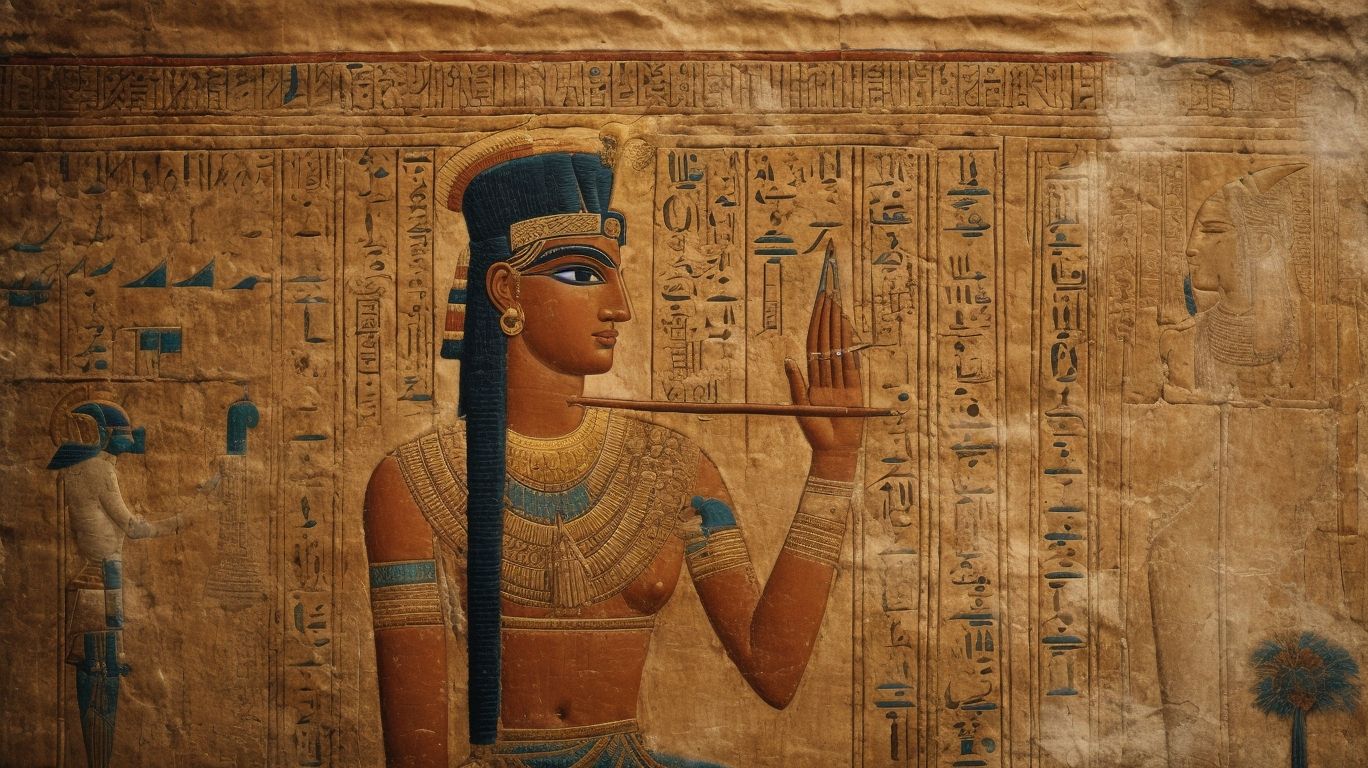

A while ago. I was browsing through a book sale and found what was professed to be an ancient Egyptian science fiction novel – Seshat (2021), by Nazli Mansour. The author is a homoeopathy expert who believes in a holistic approach to life, and this novel is a vehicle for that philosophy. I finished it in one day!

By Emad Aysha

You know what, it’s pretty good. There’s no story as such, just exposition-type recollections. You have the ancient Egyptian goddess of wisdom, writing and knowledge talking about herself and her experiences on earth, throughout human history and into the present-day world, talking about the trials and tribulations of mankind and her holy mission to set us on the right course.

Any other course than self-annihilation. And all in the service of the one true God, the creator who assigned her this task through other ancient Egyptian (and Indian) intermediaries. Who would think someone could reconcile apparent theological opposites, but you fall in love with Seshat so much that you accept anything she says at face value? She’s on our side, after all.

Despite being stilted repeatedly by boys she knew and grew up with over the aeons, Seshat loves the human race. And I mean that literally. She is constantly combating human greed and forgetfulness. Not only does the novel (which isn’t a novel) reconcile opposites on the theological and genre plain. The book classifies itself, on the front cover, as a science fiction story, while its contents and style lean towards fantasy and myths.

Nonetheless, it works. There are constant mentions of other planets and even other dimensions, updating and upgrading the imagination of the ancient Egyptians and their legends and stories to the modern world of science and advancement and a law-based perspective of the universe. Here, man’s fate, and the fate of the planet, is not determined by the whims of the tempestuous gods. It’s all in the hands of the humans, the battling wills in their troubled souls.

If they get too attached to this life, the material world of the here and now, then we’re goners. If they keep their love of the netherworld and the moral accountability that comes in the afterlife from their actions in this life, then we’re saved. There is no sense that we aren’t the ultimate masters of our fate, being hoodwinked into the illusion of free will, or that God (or the gods) is some evil entity that doesn’t trust us (at best) or is out to get us (at worst).

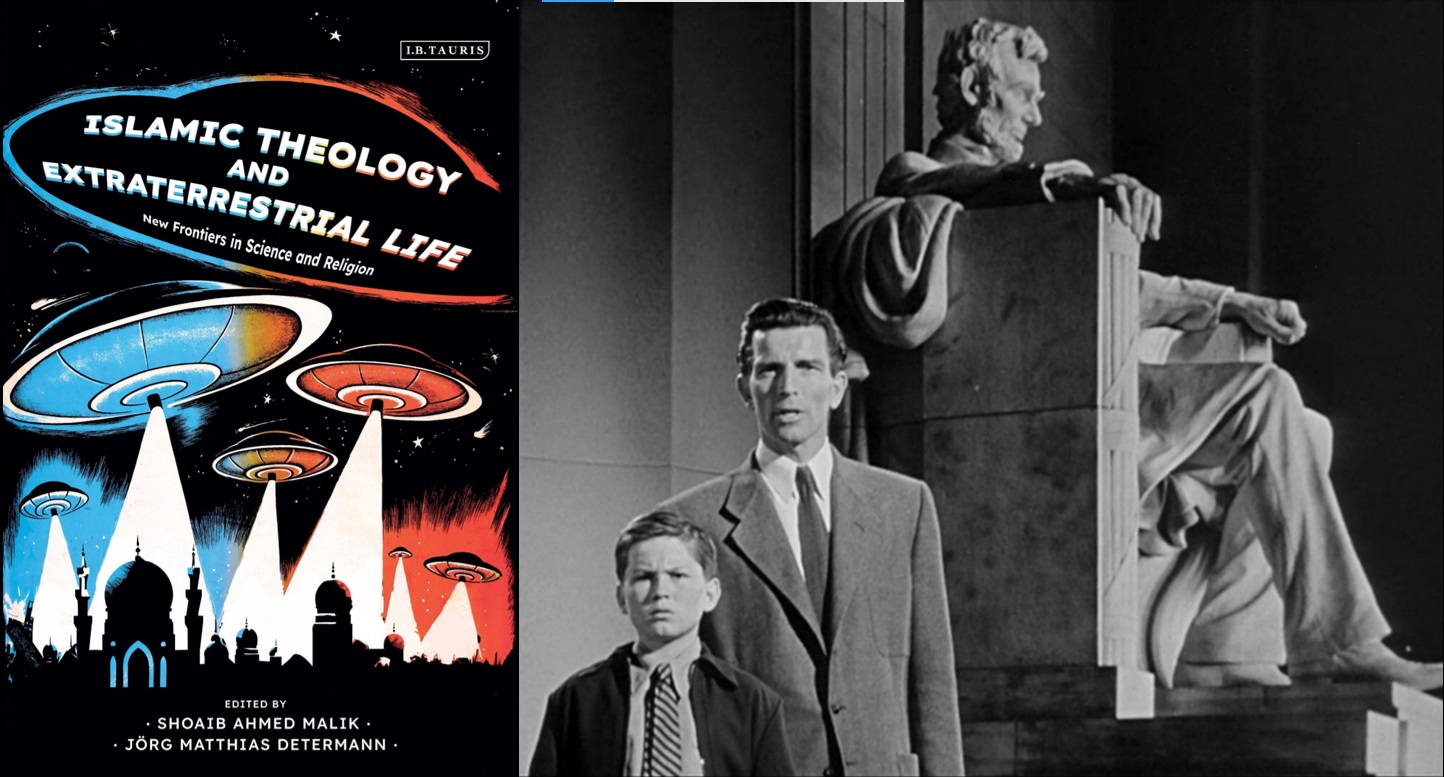

This is a far cry from what you get with Western literary and religious history, from ancient Greek myths to the present-day world of science fiction. Look at everything from Greek tragedy and how the gods and fate punish hubris in man (Agamemnon, Sisyphus, even Alexander the Great) to modern-day SF works like The Adjustment Bureau (2011), taken from a Philip K. Dick short story. And PKD was heavily into Greek myths and wrote borderline SF.

One of his most explicit stories in this regard was "Out in the Garden” in which a jealous husband gets worked up about his wife being friendly with a duck. He’s ecstatic when she gets pregnant, meaning she’ll be preoccupied with the baby, so he gets rid of the duck. Then she has the baby boy, and he has fuzzy hair-like down. When the boy finally invites his father to play with him, he eats worms and insects like a duck!

This is all inspired by the story of Zeus coming to Leda disguised as a swan to get her pregnant, and it pretty much says so in the story. And here’s a quote from his classic The Man in the High Castle: “Whom the gods notice they destroy. Be small… and you will escape the jealousy of the great.” This mindset is distinctly not Islamic and may be unique to the West—no surprise then at the distinct flavour difference when it comes to our science fiction.

PHILDICKIAN INTERLUDE: Free will has never been more in vogue, philosophically and cinematically. Don't get me started on politically, however!

By contrast, Seshat reasons with us as a race, just at a subliminal level. We are appealing to the better side of our nature and trying to find solutions and alternatives. But ultimately, we’re the ones who have to choose. And I presume she is the ancient Egyptian equivalent of Athena in Greek theology. Or should I say Athena is the Greek equivalent of the older and more benign Seshat?

A final point to make here is the status of this novel as a non-novel novel. It’s all explosion, and yet it never gets boring or pretentious, which is another contrast between modern literature and Western sci-fi. How did the author pull it off? A compromise between modern literary standards which insist on characterisation and character-driven decisions – hence the biography of Seshet we get and her relationships with us lowly humans and the gods she sees as family members and elders.

She lives in a friendly and warm world, concerned with living up to the expectations of her superiors, always being dazzled at their goodwill, and just how intelligent they are when interfering in our affairs. That satisfies the modern novel format side of things.

The other side of the compromise is our old-fashioned way of telling a story as Arabs and Easterners, which is storytelling with an individual speaker commenting on how this person does this and that person does that. It can get preachy and obnoxious, as if we’re children and don’t know who or what is going on 80 pages into the novel, but if done right, it is wholesome and lyrical.

Hence, this article. I’ll deal with the less-than-wholesome variety in coming reviews!!