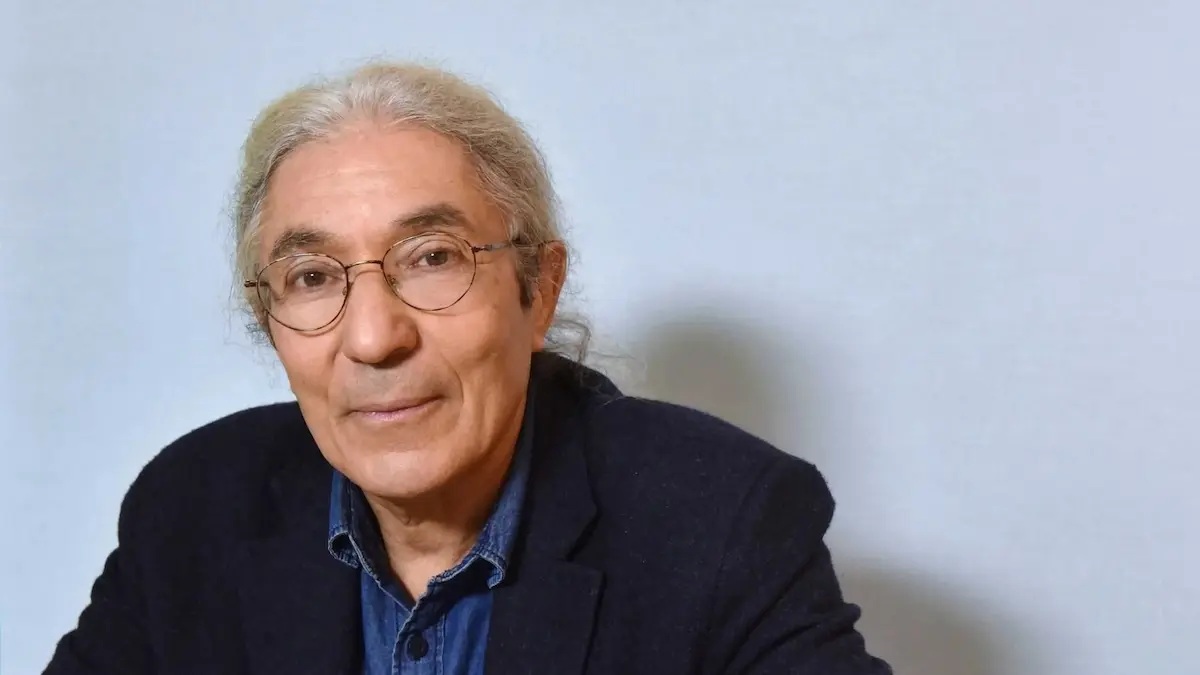

Algerian French writer Boualem Sansal, 75, has been sentenced to five years in an Algerian prison. He was arrested late last year for undermining “the territorial integrity of Algeria.” This absurd charge shows how vulnerable a writer is nowadays. The real reason for his arrest was his criticism of political Islam (or Islamism). Sansal should be immediately released.

By Paul Cliteur

In Western countries, one can be hit by a jihadist attack, as happened to the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists (2015). One may also be convicted of inciting hatred or insulting the Muslim community by a mainstream court. But one can also face draconian punishment in more dictatorial countries, as happened with Sansal.

The Algerian-born Sansal wrote novels about the danger of political Islam and corruption within the Algerian regime. For this, he received several awards in France and Germany, but the Algerian authorities of the country where he currently lives did not like his books very much. His criticism of the government, which he also expressed in essays, cost him his job as a senior official at a ministry in 2003.

The wry part of his situation is that he has also had French citizenship since last year. Sansal had already planned to live in France. He was detained after landing when he flew back to Algiers in November after visiting France.

In an interview in the French magazine Frontières, he had suggested that part of western Algeria was Moroccan territory. Thus, based on that statement, the authorities constructed a “subversion” of “the territorial integrity of Algeria.”

So, expressing a particular opinion about your country’s borders (i.e., the territory) is already seen as “undermining” territorial integrity.

Sansal’s fellow writers have protested. In an open letter, internationally renowned writers, including Salman Rushdie and Annie Ernaux, called for Sansal’s release.

Protests were also heard in France. President Macron said Algeria should release Sansal, in part because of his poor health. Sansal suffers from cancer. When it became clear that five years in prison had been demanded against the writer, another rally in Paris supported him.

But France’s protest will not do much good, as Algeria was also angered by French recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara.

The work of Sansal

The guiding idea of Sansal’s work is Islamism. For example, in his book Le village de l’Allemand ou Le journal des frères Schiller (2008), he writes about the similarities between National Socialism and Islam.

Because of his critical writings, Sansal has been under surveillance for years. He cannot walk the streets without personal security. Despite this uncomfortable situation, Sansal chose to remain loyal to his country and decided to continue living in Algeria.

Reasoning, “Just when your country is in danger, you have to be there to help it solve its problems.” Because his safety was no longer guaranteed in Algeria, Sansal had himself naturalised as a French citizen last year.

He also spent most of his time in France. But now in an Algerian prison. An ironic fate. As mentioned, Sansal’s arrest officially involves “undermining the territorial integrity of Algeria and endangering the nation.” But the latter already shows: this is a straw man. Or rather: the nation can be endangered in many ways, not least by all ofSansal’s criticisms of Islamism.

Criticism of Islamism can also be found, for example, in his book 2084: The End of the World (2015). It is a dystopian novel about an Islamic dictatorship after a nuclear disaster.

Sansal defended himself in court. During his trial, he stressed that he did not intend to harm his homeland. He was exercising his right to freedom of expression, as any citizen of the state should. He also revealed that considerations of patriotism guided him.

Although the sentence imposed was less than the Algerian prosecutor’s office demanded, it is still nothing short of draconian: 5 years in prison and a fine of 500 thousand Algerian dinars (about 3,500 euros).

Terror and preaching

After the Iranian revolution, Islamism became an international phenomenon, writes Sansal (“phénomène planétaire”). It was based on two pillars: “terror AND preaching.” The Islamists also proved to have tremendous skills in spreading their message.

That was first to Morocco and Tunisia, but later also to Europe, especially to France, a country that, in the eyes of the Islamists, should be punished for the support it had given to the impure dictatorship of Algeria. One fought under the banner of a jihad against the Jews and the Crusaders (“le jihad contre les juifs ent les croisés”) or a jihad for Allah (“le grand jihad pour Allah”).

The Afghan Taliban was also an essential source of inspiration for Islamists. They sought a “caliphate,” an Islamic state in which there would be no place for infidels. Their slogan was, waving the Koran, “for this we live, for this we die.”

In the Islamist literature circulating on the Internet, “the revival of Islam” (“La Nahda”) played an important role. Islam should regain the strength it had at the time of the Prophet and the first great caliphs.

Islamism was at stake in a terrible confrontation between radical Islamists and those in power in Algeria (1991-2006), with more than 200,000 dead, a disrupted economy, a devastated country, and a decimated elite. In 2013, the time of publication of Gouverner au nom d’Allah, the war was over. Yet it is not yet peace.

Militarily, Islamism has been defeated, but it is still present. It is rooted in the population. It is entrenched in the institutions. It constantly renews itself and adapts to new circumstances.

International Islamism has a moderate form (“la tendence modérée”) but also a jihadist variant (“la tendence jihadiste”). International Islamism aims not only to Islamize Islamic countries but also the entire world. In Le serment des barbares (1999), Sansal tried to explain the meaning of the Algerian civil war for the rest of the world in a novel form.

Islam and Islamism

Like Bassam Tibi in Islamism and Islam (2012) and Silviane Agacinski in Face à une guerre sainte (2022), Sansal distinguishes Islam and Islamism. He calls Islam a “respectable” and even “brilliant” religion (“religion respectable and brilliant”). Islamism is the instrumentalisation of Islam for a political enterprise (p. 29).

He also designates Islamism as a mixture of religion, politics and revolution (“mélange de religion, de politique et de révolution,” p. 94). He follows Gilles Kepel whom he calls the most important writer on political Islam with books such as Jihad: Expansion et déclin de l’islamisme (2000) and Fitna: Guerre au coeur de l’islam (2004).

Islamism is gaining ground not only because of the persuasiveness of its message but also because of its birth rates. Sansal quotes the statement attributed to Yasser Arafat: “we will conquer Israel thanks to the wombs of our women” (“Nous vaincrons Israel grâce au ventre de nos femmes,” p. 41).

Incidentally, Sansal also observes that the debate on Islam is almost impossible to conduct. This is not even true in Europe, which prides itself on its respect for freedom of expression. Simply uttering the term “Islam” blocks any discussion, writes Sansal (p. 56). Or it leads to a politically correct approach to the subject that disregards the controversial.

The violent reactions of Islamists to Islamic criticism also make it impossible for a critic to say what is necessary. All this means that a kind of “Berlin Wall” has been erected between Islam and criticism. People simply no longer dare say anything because they risk being accused of “Islamophobia” or of “racism” or of wanting to encourage interethnic conflict (p. 56).

The solution most people choose is: one keeps quiet. The media also conform to this rule. Sansal points to the examples of Salman Rushdie, the Danish cartoons, Robert Redeker, Taslima Nasreen, and Wafa Sultan.

Islamism “sacralises” the territory where it settles. With the construction of a mosque, for example. One indicates this is Dar el Islam (the house of Islam). Then one radicalises and comes into conflict with the other forms of faith. Islamism always claims hegemony.

It rejects religious minorities and foreign elements that only pollute its worldview, according to Islamism. It also identifies the “wrong Muslims” (“mauvais musulmans”). The wrong Muslims are the democrats, the freethinkers, contemporary women, homosexuals, and so on. And significant to the Islamists is the destruction of Israel. Israel, which is called Palestine, is preeminently Dar el Islam.

It is in Jerusalem that the prophet ascended to heaven, and Jerusalem must be returned entirely to Islamic hands. Israel, a nation with Jews, is Dar el harb: the terrain where one must wage holy war, just until the Muslims prevail. In that war, there can be no mercy for the enemy.

For the radical Islamist, Sansal writes, the enemy must be killed. And the enemy is whoever opposes the laws of Islam (“contrevient aux lois d’islam”).

Sansal also makes clear the attitude of Arab governments toward Islamism. That attitude is ambivalent. On the one hand, they fight Islamism in its terrorist variant, but on the other hand, they hand over the teaching of Islam to radical ideologues. Ideologues who transform Islam into Islamism (“idéologues qui transforment l’islam en islamisme”).

Sansal also shows how Islamism allies with a particular form of leftist engagement. Islamism, like Frantz Fanon, addresses the “rejected of the earth.”

One speaks the language of standing up for injustice. And that gives a massive boost to the spread of Islamism. Later, in Pierre-André Taguieff’s work, the term “Islamogauchism” will be calibrated: the union between the “left” and “Islamism.” Taguieff does so most extensively in Liaisons dangereuses: islamo-nazism, islamo-gauchism (2021) and slightly earlier in L’imposture décoloniale: science imaginaire et pseudo-antiracism (2020).

Do we have anything to expect from universities?

Sansal writes that in Arab countries, universities are fragile institutions (“lieux fragile”) with no tradition of criticism. Universities are easy prey for manipulators, and today, those are Islamist preachers. (Involuntarily, the question arises of Dutch universities or universities in France. Are they also heavily under the influence of “Islamo-gauchism?”).

Western governments would have much to gain from carefully studying Boualem Sansal’s work. Too much emphasis is still placed on terrorist attacks. Only when a jihadist-Islamist attack is committed do Western authorities wake up for a moment.

Just for a moment.

If anything emerges from Sansal’s work, it is that the growth of Islamism is a continuing challenge for the Western world as well. For France, first and foremost. France has the largest Muslim population compared to other Western countries. But France, with its system of the religiously neutral state (“laïcité”), has also established a state that is opposed to the theocracy envisioned by Islamists.

Islamists perceive France as a “provocation.” Consequently, in the coming period, France will become the battlefield for the battle between the principles of a secular democratic rule of law and Islamist theocracy. The outcome of that struggle is difficult to predict.

The changing demographic composition of European states creates better opportunities for Islamism. People know that. The discussion is still about “cartoons” and “headscarves” in public service. But soon it will be about the principles of the religiously neutral state. The demands of the Islamists are high; they are winning. And they know it.

It is absurd that Boualem Sansal will now spend five years in prison in Algeria. This is an outgrowth of the Algerian government's pure vindictiveness. Sansal had already announced that he wanted to emigrate to France.

Let him go.