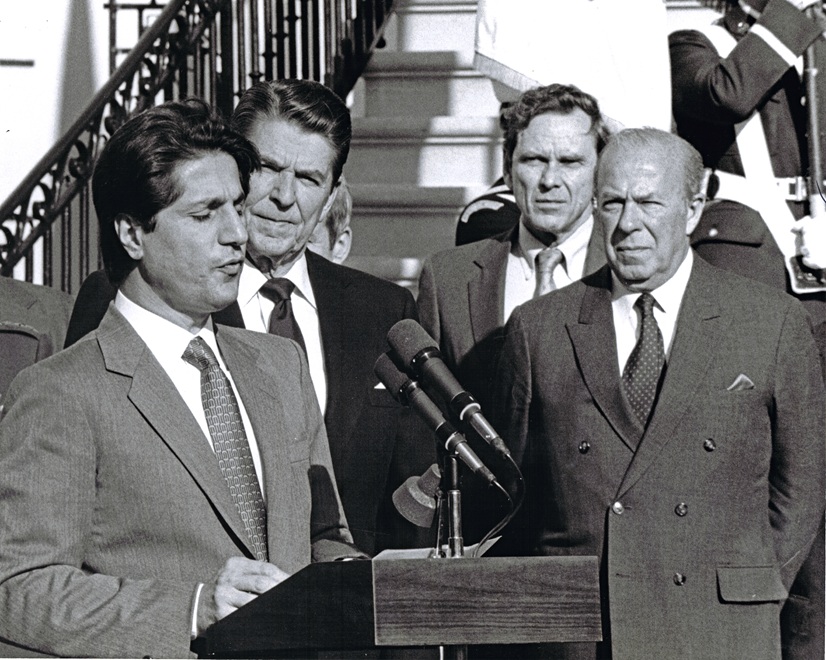

On May 17 1983, under Lebanese President Amine Pierre Gemayel, Lebanon signed a treaty with Israel, normalising bilateral relations, securing the withdrawal of Israeli troops from Lebanon under a new security arrangement. The Lebanese Parliament, which initially authorised the agreement, withdrew its support and renounced the treaty on March 5 1984. What if this agreement was ratified and implemented?

By Nadia Ahmad

Less than a year after the Lebanese Parliament voted in favour of May 17, the same Parliament voted against it, without holding a general election. Which Parliamentary majority reflected the people’s will, the one with which the agreement was signed, or redacted? Apart from the inconstancy this backtracking represents, the Parliament violated international norms by reversing their stance on a global treaty and the guiding principle of “pacta sunt servanda”.

A retrospective on the past 43 years and the current political context has redefined the May 17 agreement. With a substantial number of Lebanese now seeking normalisation with Israel, analysts must question whether this Damascene conversion is a result of a new political consciousness or a resigned defeatist approach to international relations.

Probably the latter, which dominates the Lebanese public psyche and has ironically placed Lebanon in a situation similar to 1983, where any agreement signed between Lebanon and Israel would bear striking similarity to the May 17 agreement.

After 43 years, which could have addressed Lebanon’s domestic concerns and development, Lebanon must return to the negotiation table to readdress the same points it once negotiated with Israel in 1983: sovereignty, withdrawal, and normalisation.

1983

Since 1979, the policy of exporting the Islamic revolution was among the primary objectives of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who died in 1988. The role of Iran in undermining the May 17 agreement was a result of its success in ideological exportation to Lebanese Muslim society.

From 1982 to 1992, foreign nationals would be kidnapped as political hostages by Lebanese seeking to rid the region of American influence and destroy American-Lebanese relations.

The bombing of the U.S. embassy in April 1983, two months before May 17, and the Beirut barracks bombing near the southern suburbs near the Beirut international airport, which killed 241 U.S. marines in October 1983, months before March 5 1984, was the tumultuous political context of the agreement, and its removal.

In this ideological and political context, Iran played a direct role in sabotaging the agreement through local militias and militia leaders. The suggestion of Lebanon following Iran’s example and adopting the same Islamic governance structure as Iran was a serious proposal among certain mullah regime followers.

The ideology consisted of; eradicating U.S. influence, and subjugating the state of Israel into accepting a one state solution, a Palestinian majority state from the river to the sea, where only Arab Jews may participate in a referendum to decide the future of the state and it’s constitution, while all European Jews return to Europe (the Iranian proposal for peace); two intertwined objectives in the Iranian view. The political mobilisation against Israel because of the exportation of the Iranian revolution doomed the agreement.

In 1982, Israeli troops entered Lebanon, starting the first Israeli-Lebanese war. The 1983 agreement, which would have secured the withdrawal of Israel, was overthrown by militias seeking to undermine President Gemayel, forcing him to send a bill to Parliament in an almost coup d’etat.

They also divided the Lebanese army on a sectarian basis. In favour of blaming foreign governments, the role of the dicey Lebanese Parliament is overlooked. The requirement of a majority decision means that the same majority which signed the agreement removed it 10 months later.

1993

On the Palestinian question, the Lebanese have proven to be “plus royaliste que le Roi”. While the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) secretly negotiated with Israel for a decade before the 1993 Oslo Accords, the Lebanese-Israeli treaty was disregarded, as the Lebanese continuously backed the Palestinian cause, only for the PLO to enter into their own agreement with Israel. Meaning the Lebanese supported the Palestinian cause more vehemently than the Palestinians, at the expense of their own national interest.

The Ta’if agreement of 1990 was introduced and implemented under the guise of “political resolution”. Instead of resolving political problems, removing the Presidential system guaranteed decades of political stagnation, corruption, and deadlock that characterised Lebanese politics for decades to come.

The Cabinet became the Lebanese version of the “Wolesi Jirga” in Afghanistan, at the expense of the Christian community, who were deprived of power. Any normalisation under the Ta’if system would require a cabinet consensus, which is impossible to reach.

The 1990s were dominated by Prime Minister Rafic El Hariri, who proposed no political solutions to Lebanon’s crises. The Hariri government prioritised development over politics, a failed approach to governance, as political crises should be addressed before infrastructure development. Had the development-first approach succeeded, Lebanon wouldn’t have remained both an infrastructural and a political failure.

2003

The Muslim Brotherhood came to power in Turkey in 2003, ushering in the era of regional Islamist politics. This new political context lent an Islamic basis for opposition to Israel in support of “Palestine”. The question “Why should Israel be a Jewish State” was now being posed by Islamic regimes, not secular governments.

In Lebanon, security concerns remained high and unaddressed. The Israeli withdrawal from Lebanese territory in 2000 did not address security or lead to any security arrangement. Instead, both parties were working towards the next round of conflict, which broke out in 2006.

With no viable solutions, the temporary solution of Israeli withdrawal was a pyrrhic victory, with the main foreign policy objective being “the liberation of Palestine” instead of safeguarding the national interests and security of the state.

2013

In 2011, the Arab Spring, also known as the Arab Fall, ushered in the Islamicist Rise. Supported by the regime of Barack Obama, the Clintons, and the notorious Epstein gang, the Islamic Brotherhood Spring took over Egypt, Tunisia, and Gaza.

The Muslim Brotherhood fought against the government of President Bashar al-Assad in Syria, leading to the influx of 1.5 million Syrian refugees into Lebanon, further igniting the same sectarian tensions of the civil war. The Turkish proxy war in Syria was also fought by Hamas, against the Syrian army, which was no longer a Palestinian movement but a non-governmental tool in the service of the Muslim Brotherhood.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s regional actions led to political and social instability in Lebanon, fuelling sectarian tensions and leading to numerous clashes in the 2010s between Lebanese. Had the May 17 agreement remained, 1.5 million Syrian refugees, many of whom entered Lebanon illegally, would not have been able to enter Lebanon, as Lebanon would have had strong borders.

An absence of resolution at the Southern Israeli border led to weak borders with Syria, and chaos after a mass Syrian influx into Lebanon. Had Lebanon upheld May 17, then Israel would have objected to over a million Syrians entering Lebanon, as it is also a risk to Israel’s national security through the infiltration of the Lebanese border.

The 2019 Lebanese revolution was the only exception to the Arab Spring, with relatively secular and noble goals for the state. An Islamic non-governmental actor ultimately aborted the 2019 revolution. Had Lebanon remained in the May 17 agreement, the demands of the Lebanese protesters by 2019 would have been moot, as a border settlement would have resolved Lebanon’s domestic problems. May 17 would have guaranteed foreign investment in Lebanon, a stable currency, and economic growth.

The political paralysis, which is a direct result of the Saudi-backed Ta’if agreement, the Syrian refugee crisis, and security clashes between sectarian factions, would not have affected Lebanon by 2013 had May 17 been upheld.

2023

Launching a war from Lebanon in support of the Palestinians, when the Palestinian Authority maintained a “business as usual” approach to their normalised relations with Israel, was the ultimate disregard of national interest. Before October 7th 2023, Hamas was ruling a relatively prosperous Gaza, with functional universities and hospitals, with the approval of Israel.

Lebanon, more Palestinian than the Palestinians, and more Syrian than the Syrians, lost the war with Israel and is now forced to negotiate Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon. Once again, the curse of March 5 (when May 17 was redacted) showcases that every crisis in Lebanon would have been prevented by upholding May 17.

Lebanon must now enter negotiations with Israel to reconfirm terms agreed in 1983, after 43 years of development, thereby losing its regional status and international reputation and bypassing an entire generation that suffered the consequences of political stagnation and failure.

Today, the same people who prevented May 17 from being enforced are looking towards Israel for an agreement. Can the catalysts for war become the catalysts for peace? What is certain is that the Lebanese must abandon their reliance on fourth-dimensional victory and the illusory “Palestinian liberation” dream.

Before the war with Israel, the Lebanese were postponing any negotiation on borders with Israel due to the Iranian nuclear programme, among other reasons. Instead of operating as a pawn on the regional chessboard, the Lebanese must look to their national interests alone.

43 years behind

The 43 years lost by the Lebanese political “naivety” is a historical lesson. Many of the crises and problems which have plagued Lebanon since 1983 would have been conclusively resolved by the May 17 agreement. Considering how the last Lebanese-Israeli war ended, and the renewed demand for peace, one must wonder why Lebanon did not simply uphold the treaty signed under President Gemayel.

The May 17 agreement specified a proposal of a demilitarised zone controlled by the Lebanese army, just as Lebanon is negotiating today in an effort to secure Israeli withdrawal. How the Lebanese allowed 43 years to pass only to come back to their 1983 political problem is confounding.

Lebanon once held a regional position comparable to Dubai's. As Lebanese flock to Dubai in large numbers, they should be reminded that it was once Beirut, not Dubai, that held the position of the region's cosmopolitan hub.

The Maronite Patriarch’s proposal of active non-alignment is the ideal solution for Lebanon. Yet, the fact that this came from a religious, not a political leader, further exemplifies the political ineptitude of successive Lebanese governments.

Since the Lebanese wasted 43 years of their personal and the state’s political life, only a similar May 17 agreement is required to save themselves; thus, it appears that, for President Amine Gemayel, time was the ultimate vindicator.

The only President who had his own think tank, “Beit Al Mustaqbal,” with its own newspaper, “Le Reveil,” was effectively exiled in the 1990s to the U.S., where he became a lecturer at Harvard University and articulated the Lebanese national interest decades before the establishment of the state.

The character assassination of President Gemayel by the left-wing propaganda machine in Lebanon was carried out not by the secular, but sectarian left-wing factions who have contributed to decades of political gridlock and negligence. Ironically, calling the President the “Shah Baabda”, comparing him to the Iranian Shah Reza Pahlavi, who was deposed by the Islamic revolution.

The nation required 43 years to achieve peace.