Known as Burma during British colonial rule, Myanmar remains largely unknown, including its significant ethnic diversity. It ranks among the top five countries for diversity, alongside India, Indonesia, China, and Russia. Since 1989, the country has been primarily led by a military junta, which claims to unify the nation for the greater good. Amid these promises, who benefits when access to the truth is limited?

By Wouter van der Wiel

"We must use any means necessary to protect the country from chaos." Famous words spoken by General Ne Win, Burmese military leader and politician

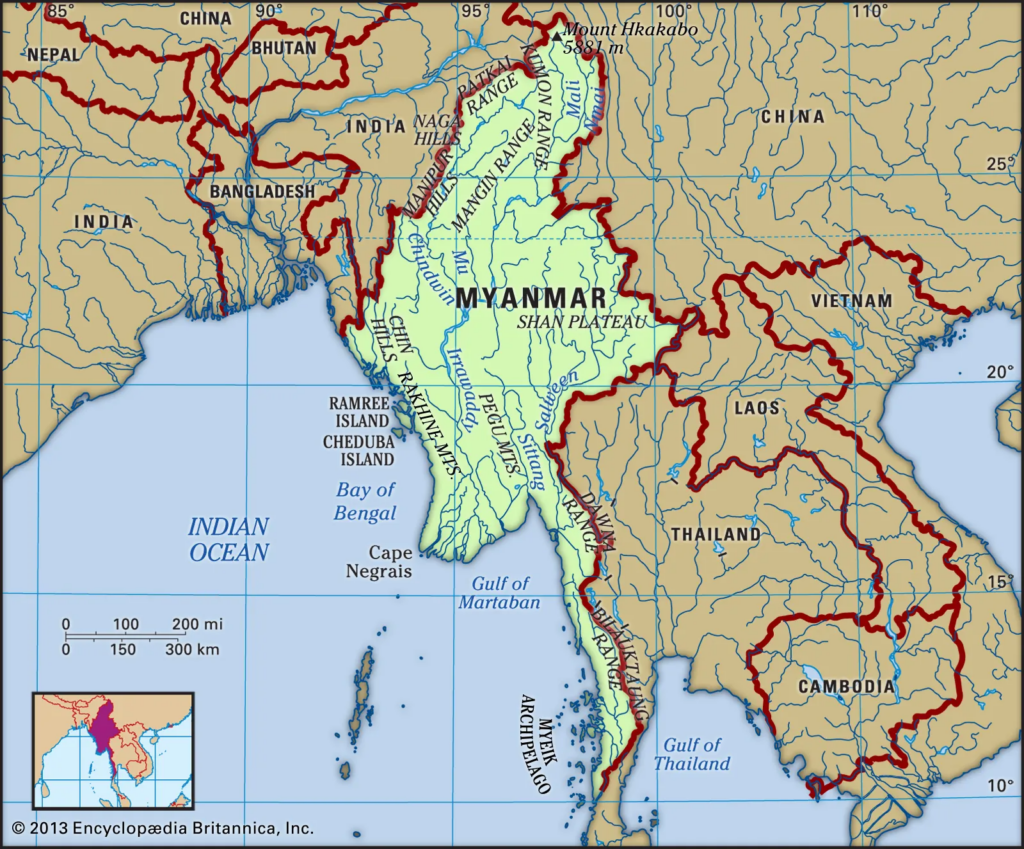

Myanmar's current name, also adopted in 1989, was part of a broader initiative by the junta government to revise colonial-era names and symbols. Myanmar better reflects the country’s diverse ethnic groups.

The turmoil within Myanmar and the negative portrayal of the junta stemming from ongoing conflicts, human rights abuses, and political repression have overshadowed the junta's intentions when its relations with the Russian Federation are being taken into consideration.

Unraveling Myanmar's intricate historical context, often overshadowed by negativity, is crucial. Just as Russian President Vladimir Putin has offered a historical perspective on the situation in Ukraine, a deeper understanding of Myanmar's past can shed light on its present.

While the degree and nature of instability in Myanmar have varied, the country has faced significant turmoil for over 60 years.

Aung San Suu Kyi

In 2016, the United States imposed sanctions on Myanmar to foster its transition to democracy and integrate it into the U.S.-led global economy. Myanmar saw semi-democratic reforms under Aung San Suu Kyi from 2016 to 2022. Still, these ended abruptly with a military coup in February 2021, which restored military rule and led to political instability and civil unrest.

The U.S. and UN sanctions, designed to drive political change and promote U.S. investment and NGO involvement, have had a significant impact on Myanmar’s political landscape. Understanding this influence is crucial for staying informed and aware of the global geopolitical dynamics.

Because mainstream media often reports in a biased manner, it is difficult to understand situations from a complete perspective. Important information is frequently omitted, misrepresented, or demonised. Counter-information can only be found through extensive personal research into non-mainstream media, such as sources from Russia, China, India, Vietnam, and Myanmar.

Media Bias

Living in the region for five years, travelling extensively, and consuming mainstream media coverage of the situation in Myanmar, I have noticed that the reporting is consistently one-sided, particularly from 2016 onwards. This pattern of bias mirrors what has been observed with coverage of other significant issues, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ukraine-Russia conflict, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

In each case, Western mainstream media often presents a skewed perspective, highlighting certain viewpoints while neglecting others. This recurring issue underscores a troubling trend of partiality in reporting.

Western media bias is a recurring issue across various topics, often characterised by a lack of broader context and historical depth. Although some aspects of the problems are covered comprehensively, many others are not, and we rarely hear the full spectrum of perspectives.

As a result, we are increasingly neglecting the vital practice of independently challenging conventional viewpoints and established ideas through counterintuitive or unconventional thinking.

This approach allows us to question assumptions and explore alternative perspectives on our own terms rather than being swayed by prevalent biases. Engaging in this self-driven analytical process is crucial, even if the outcomes challenge our personal preferences or comfort zones.

For example, Myanmar's recent events legally do not qualify as a coup. Under their 2008 Constitution, recent developments align with the legal framework provided. The constitution permits actions such as arresting officials and cancelling elections under Articles 417 and 418, which allow the president to declare a state of emergency and transfer power to the supreme commander. Thus, these events remain within constitutional boundaries and are not formally classified as a coup.

There is minimal discussion of the details, but Western media richly portrays the situation as a military coup.

Another interesting perspective is the role of George Soros' Open Society Foundation (OSF). Recently, the regime seized $3.81 million from private banks and $1.4 million from the Small and Medium Enterprise Development Bank, all belonging to the OSF. Although these amounts might seem modest, they are strategically significant in Myanmar. The funds are intended to support activities to create unrest, promote specific ideas, and finance payments to senior politicians and local authorities to influence and secure desired outcomes.

The regime accuses OSF of financial improprieties and illegal withdrawals and has issued arrest warrants for 11 OSF staff, including top management. The government also claims OSF attempted to influence Myanmar’s politics and accuses Aung San Suu Kyi of meeting with Soros, which OSF denies.

This case involving the NGO Open Society Foundations (OSF) starkly illustrates the extent of Western involvement in Myanmar’s foreign affairs and reveals who benefits from this involvement. Meanwhile, the media continues to depict Myanmar as welcoming 'Western democracy' despite the current reality. This portrayal conveniently shifts the focus, placing all blame for undemocratic actions solely on the junta and overlooking the broader context and complexities of the situation.

Military Control

The northern part of Rakhine State, particularly around Maungdaw, Buthidaung, and Rathedaung townships, has been a hotspot for recent violence involving ethnic armed groups and the national military junta. "Rakhine" and "Arakan" refer to the same region in Myanmar, but the names reflect different historical and linguistic contexts.

Myanmar’s population is 90% Buddhist, with 5% Christian and smaller Muslim and Hindu communities. The 1982 Citizenship Act denied citizenship to the Rohingya, who are deemed illegal immigrants from Bengal.

The Western media often highlights single incidents and exaggerates their significance, particularly regarding the humanitarian crisis, human rights, and genocide. It is important to note that the United League of Arakan (ULA) and its armed wing, the Arakan Army (AA), are working together to establish an autonomous region within Myanmar, and their military and political activities toward this goal are frequently ignored or underreported.

The AA's conflict with the Myanmar government, driven by its advocacy for the Rakhine ethnic group, leads the media to amplify the need for substantial external support to rebuild Rakhine State. This potentially increases international leverage on the Rohingya issue. However, the media often neglects the junta government’s efforts to maintain national unity in Myanmar, which could provide a fuller understanding of the conflict’s complexities.

A Bigger Picture

There is a need for a broader look at the turmoil in Myanmar. Foreign interventions have significantly contributed to Myanmar's political and national situation. Interventions from the UN, the US, the collective West, and NGOs are all involved. The military coup in February 2021 halted the country's "semi-democratic reforms," which have influenced the nation's trajectory—essentially, I can describe the situation as a coup within a coup.

Myanmar is probably of interest because of its strategic significance, including its role as a land bridge between South and Southeast Asia, its access to key maritime routes via the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea, and its wealth of natural resources such as oil, gas, and minerals. These factors justify Myanmar's regional influence and international interest, which includes the U.S./UN and Collective West, but also China and the Russian Federation.

Limited information about Myanmar's junta is due to internet restrictions and government-imposed limitations. Given past experiences with Western involvement, this lack of transparency may be intentional. However, the junta acknowledges the need for geopolitical balance, which includes avoiding excessive reliance on China. The current interest in BRICS reflects regional geopolitical dynamics, including its alliance with the Russian Federation. BRICS is also drawing increasing interest from countries seeking balance in a multipolar world. Consequently, Myanmar’s strong relations with Russia and China, both prominent BRICS members, are understandable.

Earlier in 2024, before the upcoming BRICS summit in Kazan, Myanmar sent delegations to the Eastern Economic Forum (EEF) and the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF). As of 2024, Russian President Vladimir Putin has emphasised that family, moral values, and religion are central to national policy. These statements align with Russia’s broader political agenda, which combines a commitment to conservative values with a strong emphasis on national unity and identity. The Eastern Economic Forum also aims to foster and boost business relations between ASEAN countries and Russia.

The prevailing narrative about Myanmar often depicts the junta as the sole antagonist and as enforcing a harsh dictatorship. This raises the question: Is this the complete picture? It is also noteworthy that the junta, having learned from past experiences, seeks to maintain national unity and forge new alliances with BRICS countries and Russia. These efforts appear to be genuine.