There’s nothing quite like size on the silver screen, even the TV screen. One case in point is Caligula (1979), with Malcolm McDowell as the titular Roman tyrant.

By Emad Aysha

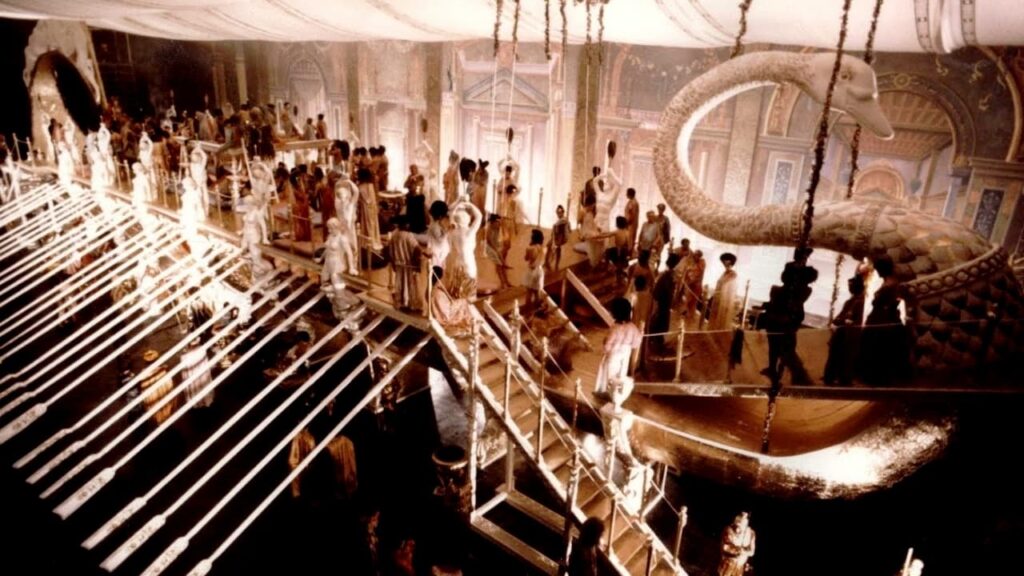

I had the good fortune of watching the restored cut, minus all the porn and all the script. Not that it isn’t raunchy as hell. Still, the movie's real focus was how ‘big’ it all was, even though it’s done in theatre mode.

You can tell these are theatre sets, having a deliberately flat feel, just like in a play. And yet they are so effective because of their size and the clever usage of colour. Some sets are almost all bright red, others all dark blue, and others all purple or plaster white.

UNHOLESOME ANTICS: Malcolm McDowell as the infamous Caligula, with his twin sister Drusilla (Teresa Ann Savoy). Talk about too close for comfort!

The single block of the same shade of colour leaves an impression on your retina, mind’s eye, and visceral senses. Not that there isn’t any detail or other colours, but given that the visual style is theatrical too – the camera is almost always level with minimal close-ups – you need such block colours and gargantuan sets to pulverise your sense of morals into putty.

If you live in a world this big, you have to go mad with power and suffer from acute bouts of paranoia that somebody is going to take it all away because there is so much to take away. Pure genius.

The movie is a masterpiece for another. It’s almost three hours long, and you hardly feel the time, and this is despite the absence of action since it’s essentially all talking inside rooms. (With a lot of fornicating, to be fair.) The music does the trick.

LIFE AS STAGE: A man with no battles to his name like Caligula sure knew how to compensate with the spectacle of mock(ing) victories.

John Carpenter has been known to do subdued soundtracks that leave you edgy and receptive to what comes next: violence, action, or speed. The same here. The music feels like a steady rumbling, meant to help you feel what’s going on and push things along by creating a sense of momentum. More than that, a sense of momentum like a truck that will crash soon, leaving you flattened to a pulp.

That’s exactly what happened. The decadent emperor keeps pushing it until those around him can’t take it anymore, and he and his loved ones meet an incredibly sticky end.

It’s a perfect indictment of hegemony, if ever there was one, whether from individuals or entire nation-states. But that’s beside the point. I’m only bringing this up to once again mention Dune Part One (2021) compared to David Lynch’s Dune (1984).

Some of the scenes in Caligula are nearly identical, in terms of emotional and sensory impact, to the older Dune movie – specifically in the sequence on Giedi Prime when you see the Harkonnens for the first time, with all their surgical cruelty and taste for industrial opulence on display.

The only difference is that Lynch’s Dune is more movie-oriented, with camera angles exaggerating the size of things and following actors as they move. There’s also intelligent usage of lighting since you become more aware of size when you see beams of light coming towards you from a distance. More so if there’s dust, humidity or smoke in the air.

BACKDROP TO EVIL: Kenneth McMillan as the over-the-top Baron Harkonnen. Note how everything that's green isn't necessarily organic.

Poor David Lynch, a man who adapted to the source material and the genre, also adapted to the scale of his actions in those scenes. Can we say the same about you-know-who regarding Dune (2021)? Absolutely not!

I was watching a YouTube video once about naturalistic paintings of landscapes and how an individual is always put in the foreground to help you judge size, and straight away, I thought of the 2021 Dune, only for the video itself to mention Denis Villeneuve’s said movie.

But that’s the wrong approach. In a moving picture, unlike a static painting, you need angles and lighting to convey things like size, especially if you’re using miniatures. I know that Caligula didn’t do this, but given the theatrical filming style, it relied instead on using simple block colours.

What mathematical proportions don’t do, emotions do. Caligula and Dune 1984 pull off this feat, whereas Dune Part One doesn’t. Caligula is even better at world-building because the mad emperor at one point escapes his palace and lives with the dregs of society, showing you what life in the sewer looks like and how people at the bottom of society live.

By contrast, Dune 2021 is all set indoors, with the elites, while the only time you see the city of Arakeen is from the top level in the sky, with no single sole anywhere in the streets. How could they forget such an important and bloody obvious detail?

MISSING IN ACTION: When you play around with AI image generators and say city, its often gives you the buildings minus the people. This screenshot of Arakeen from 'Dune' (2021) is even worse. You can't tell the city from the desert!

This bodes badly for the forthcoming Dune Messiah, which ideally should be governed by the same aesthetic and psychodynamics as Caligula. Then, there’s the soundscape to take into consideration.

You don’t have to overwhelm people with emotions when it comes to music. You have to use it to set the ambience for the movie or individual sequences and, critically, use it to create a sense of pacing, not to weigh people down.

I ‘felt’ the time when I was in the movie theatre watching Dune Part One, and at the same time, I didn’t feel the space. Things were huge, alright, to the point that you had to squint your eyes to see something in the back end of a room, but it still didn’t feel significant enough.

The size is meant to serve as a thematic point. Decadence and the struggles within. God help Frank Herbert in his grave!!