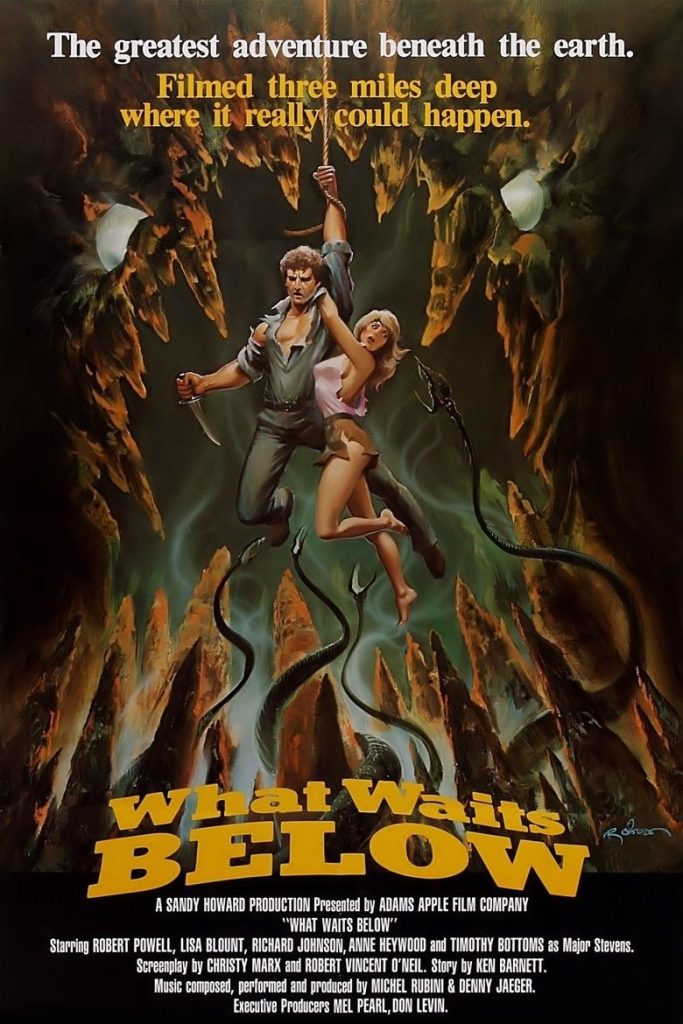

Some classic movies have various layers and multiple interpretations. Like the classic British horror/sci-fi movie, What Waits Below (1984). Besides that, it is pretty good, perhaps a bit corny; there’s more to this movie than what is evident on the surface!

By Emad Aysha

The story centres on an archaeological dig in Latin America, with the US Army wanting to push the experts aside to use the cave for a state-of-the-art communications experiment. The man in charge, Maj. Elbert Stevens (Timothy Bottoms) is a Vietnam vet.

The scientists are a mixture of Brits and Americans, an early indicator in itself. At the same time, the independent contractor read mercenary the army hires to get into the cave is Briton – Rupert 'Wolf' Wolfsen, played lovingly by the gentleman rogue Robert Powell. And yes, the wolf is for lone wolf. (Boo, hiss!)

Typically, things go badly wrong. The cave complex is populated by underground residents, primitive humans that have evolved for the dark environment, with albino features, heat-sensitive eyes, and hypersensitive hearing. The cavemen attack the soldiers and steal the transmitter, forcing the army to let the scientists back in, with Wolfsen leading the way.

All the Major thinks about is promotion, so he insists on turning on the transmitter again, his men be damned, and that the primitives attack because the sound is unbearable for them. While they are ‘savages’, they’re not evil. They are defending their terrain at the end of the day, compared to the trigger-happy Major.

They also have a modicum of technology, can spin their own clothes, and most of all have their own rules. In a key scene, Wolfsen fight for one of the archaeologists – his girl – in a fair fight with a prominent caveman and spares his life. The tribal elder gives him the necklace of the defeated warrior and lets him take the girl back.

CAVE IN: Notice that the very British hero Robert Powell has dark hair, but he 'still' gets the very blonde all-American girl in the end.

By contrast, the Major is reminded by Wolfsen, early on, of his sordid career in Vietnam, when it came to forcefully repatriating people. But it’s also notable that the archaeologists, the Brits at least, get killed compared to the American girl and Wolfsen.

You get the distinct impression that the dead duo are too enamoured by the past, walking to their own death, whereas Wolfsen is the go-it-alone type. He loves history, no doubt, but doesn’t linger on it, hitches with a young American bride, and most importantly, refuses the designation mercenary.

He’s too free-willed to take orders from anybody, whatever they pay. And he also gives the necklace back to the warrior, asking for safe passage out of the cave complex. This charts a course for Britain in the post-imperial world, grounded in fair play and putting the colonial past behind it.

Not to mention a proper relationship of mutual respect when it comes to the Americans – the so-called ‘special’ relationship.

The movie was also quite prophetic about what is happening in the US today, with President-elect Donald Trump appointing Keith Kellogg as the envoy to Ukraine. And, you guessed it, he’s a Vietnam vet.

There’s a country that hasn’t put its past behind it!

You also feel the movie still has a deeper lesson to teach. There’s a scene where they find these phosphorescent things dangling from the cave’s ceiling, with the glow being used to draw insect prey to its doom: greed, in other words.

The first time you see Wolfsen, he’s spying on some expeditionary party. While the mercenaries speak Spanish, their boss seems to be German. (Wolfsen is also very respectful of the Latin soldier assigned to him, treating him as an equal).

At the end, Wolfsen and the American girl tell the Latin attaché to the US army that the experiment was a failure, a cave-in happened, and that they’ll have to seal the cave (once again) forever. They’re preserving that bygone culture on the inside, unsullied by modern civilisation.

Compare that to a similar movie, The Mole People (1956), in which American explorers find a remnant of the ancient Sumerian civilisation in the Himalayas, surviving a flood and becoming dependent on the darkness. Here, the Sumerians enslave the so-called mole people, and the American heroes end up killing everybody.

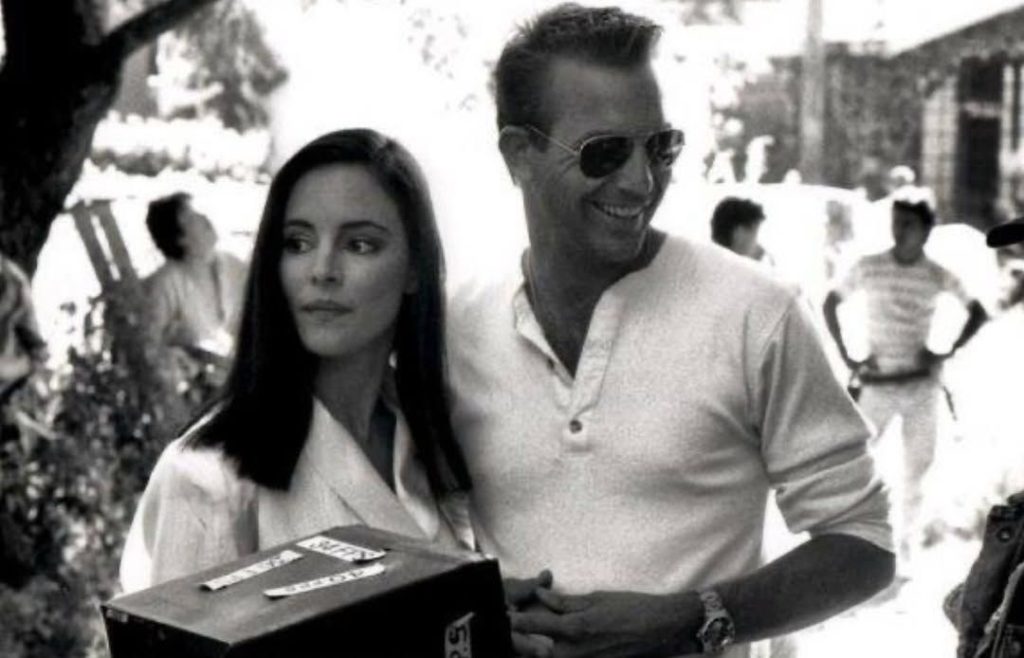

TRESS PASSED: A screenshot from 'Revenge' (1990). Kevin Costner, typically, is the well-intentioned Yank (imperialist) and Madeleine Stowe as the ultimate Mexican (booby) prize.

Even the one nice person, a blonde girl they save, dies as well through a freak accident. The message is, the past can’t be allowed to live, no matter how civilised. It's the American way or the highway. And the mole people are a symbol of the oppressed masses of the world, kept in 'the dark' by their masters.

The only catch is that the mountain guide for the explorers dies in a freak accident himself, not being a whitey.

In What Waits Below you can’t help but notice that the first two victims of the cavemen are an American GI and a Latin American soldier. And the Latin guy is asking the GI to describe the US, very expectantly.

The GI, for his part, comes from a small town and is very homesick. Both are cannon fodder, in other words, and there is a clear allusion here that America should lead by example. Not brute force, let alone careerist opportunism.

Immortal lessons once again. You can see that very ‘British’ lesson in the closing sequence in Tony Scott’s Revenge (1990), with Kevin Costner begging Anthony Quinn to tell him where Madeline Stowe was.

Needless to say, marital betrayal is a big deal in a country like Mexico, and Stowe got dumped into a brothel and given drugs. The closing scene is in a mountain-top monastery, where she is.

Sadly, it’s too late; the drug addiction has killed her, dying in Kevin Costner’s arms. The mountaintop image is the classic city-on-a-hill motif, again leading by example. If you intervene in a country’s internal affairs, however well-intentioned, people die.

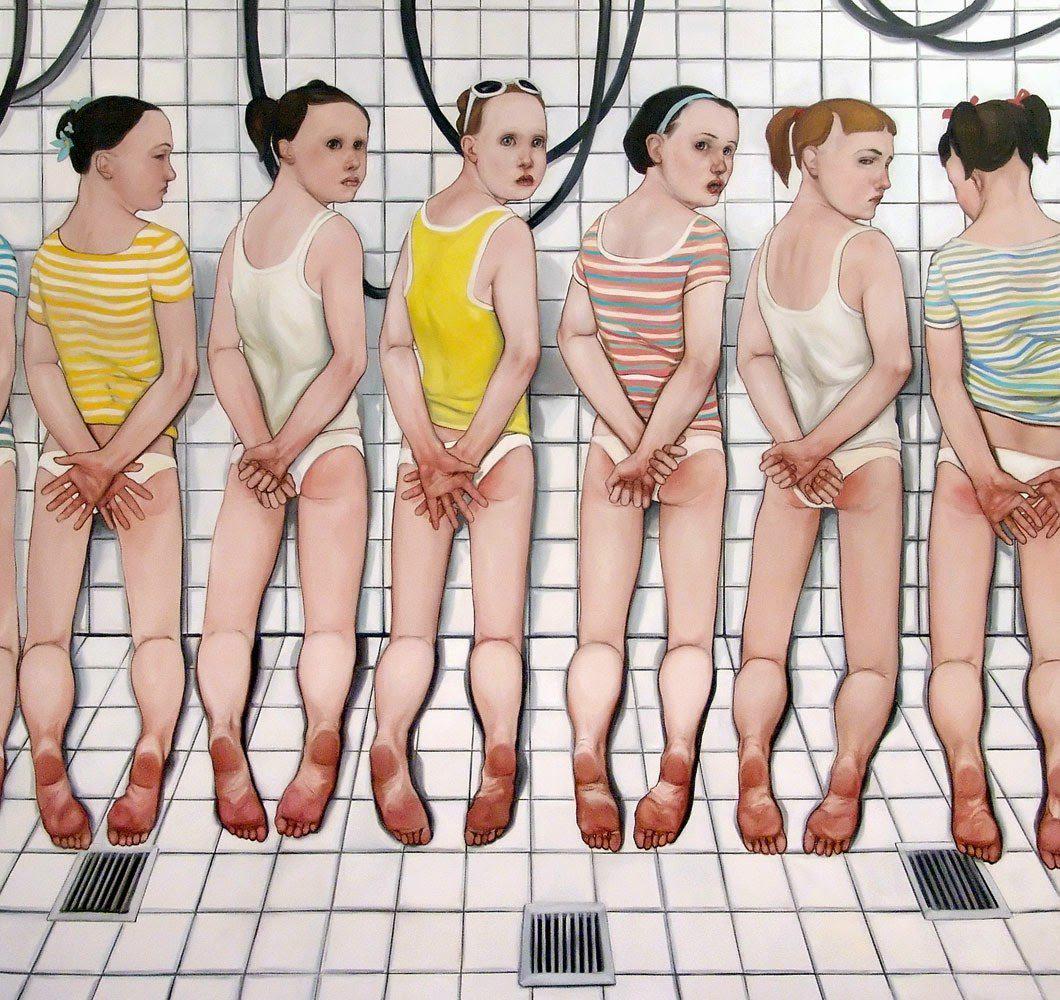

ALBINO REFERENCES: A screenshot from 'The Mole People' (1956), the last remnant of a lost civilization that the Americans insist on destroying through democracy.

Quinn’s character actually loves Costner and tried to give him a chance to leave before it was too late – he’s the only guy who doesn’t lie to him.

Again, lessons lost on ‘young’ nations.