“(O Prophet), good and evil are not equal. Repel (evil) with that which is good, and you will see that he, between whom and you there was enmity, shall become as if he were a bosom friend (of yours).” --- Quran, 41:34

I was asked a long time ago to write an academic article on the ‘new rhetoric’ in Arabic science fiction, citing an introductory remark about a particular SF novel written by an Egyptian friend. For the life of me, I couldn’t make sense of the proposition.

By Emad Aysha

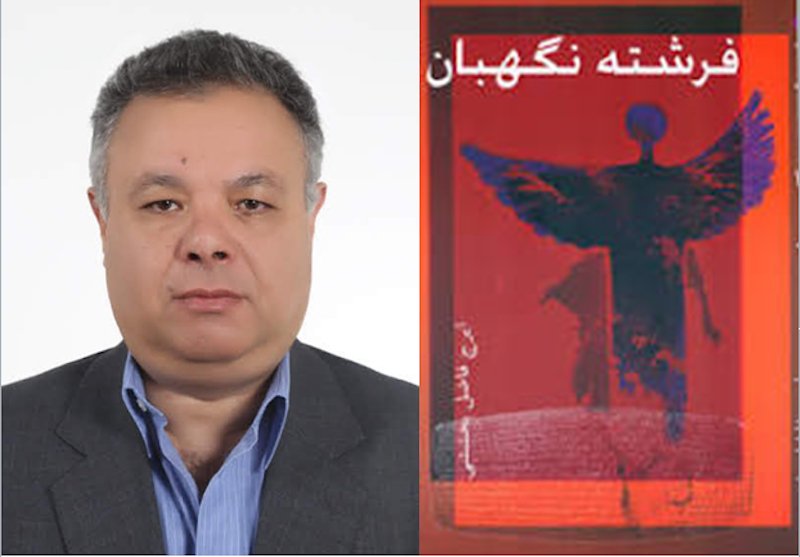

I searched online and downloaded heaps of pdf documents on the new rhetoric in the Western literary tradition and still got nowhere. Then, by happenstance, I was reading a hastily translated text for a beautiful SF novella, Guardian Angel (2016), by an Iranian friend – Iraj Fazel Bakhsheshi – I finally understood what I’d been tasked with all those years ago!

Talk about loopy logic. When researching that belated article, I came across an Iranian publication with an academic piece on traditional storytelling techniques in Farsi literature, emphasizing parables and moral lessons and oral storytelling as opposed to characterization and plot and depth and realism; modern literature in a word.

We have the same mindset in Arabic literature, but reading Mr. Iraj set me straight about the new rhetoric that is springing up in Arabic, and Muslim, SF. In summary, Guardian Angel is set in the distant future where Earth is at war with Mars. The Martians are losing against the united nations of the earth (that’s not a pun, but a literal reality), and in a last-ditch effort, they use time travel to go to our day and age.

Why? To steal a relic from an Iranian museum that will allow them to travel further backwards in time, to the time of Cyrus the Great, and kill the man and prevent him from authoring the relic in question – the Cyrus Cylinder, containing in its folds the first-ever universal declaration of human rights.

Destroying this will swerve human history in the wrong direction, making the future Earth an easy game for the Martian fleet. The characters in the novella are never named. They are always described as the middle-aged man, the security guard, the detective, the man with red hair, the thief, etc. This is true to the moral parable in both Arabic and Farsi traditions.

Characters are often cardboard cutouts with no volition or nuances of their own. But on closer inspection, however, you find that the erstwhile hero, the detective put in charge of finding the Cyrus Cylinder, does have his unique personality and character arch of sorts as he’s grumpy and doesn’t see this theft as deserving of his attention.

Its’ not like the Cyrus Cylinder was made of gold or anything, merely clay, as he constantly reminds himself and the people he speaks to. Nonetheless, he is no anti-hero. He’s a dedicated cop and a thorough and intuitive investigator, and his grumpiness results in part from the tardiness of others. He figures out where the Cylinder is and uses forensics and CCTV to track down the thief.

The criminal he brings in for questioning likewise has a quirky character. He’s proud of his skillset and doesn’t expect to slip up. He’s also entirely rational and cooperates when he finds that he’s been discovered by the highest authorities in the land.

(There’s even a nice scene where one of the criminals decodes the time signature on the Cylinder and gets a soda pop, even after being reprimanded to work harder. Simply everybody is memorable!)

The detective tracks down the man on the inside, so to speak, and gets into a gunfight, only to find himself teleported back in time. That’s when he meets the real criminal mastermind, a red-haired individual – a reference to the ‘red’ planet, although I see him as a stoolpigeon for Yankee imperialism – who is thoroughly human but a mercenary in league with what he considers to be a superior race.

The man is cold and calculating and a disgrace to humanity, but he is not a comical character. You enjoy yourself when the hero guns him down. The man also explains his master plan, which looks like a ploy, but it feels perfectly natural here. (That’s more than I can say for most Hollywood movies, especially the superhero variety). As he sees it, working for the winning side should fill him with overconfidence.

The ending is happy by all means but not in the traditional fashion, with tremendous sacrifices and profound historical lessons being learned. The Cyrus inscription is juxtaposed to the criminal exploits of older emperors and kings from Babylon and Assyria, and boy, do you notice the difference.

This is a lovely melding of new rhetoric and modern literary traditions, emphasizing the novel and character arches, personality profiling and complex plots, and traditional storytelling techniques about the punchline and clarity of purpose.

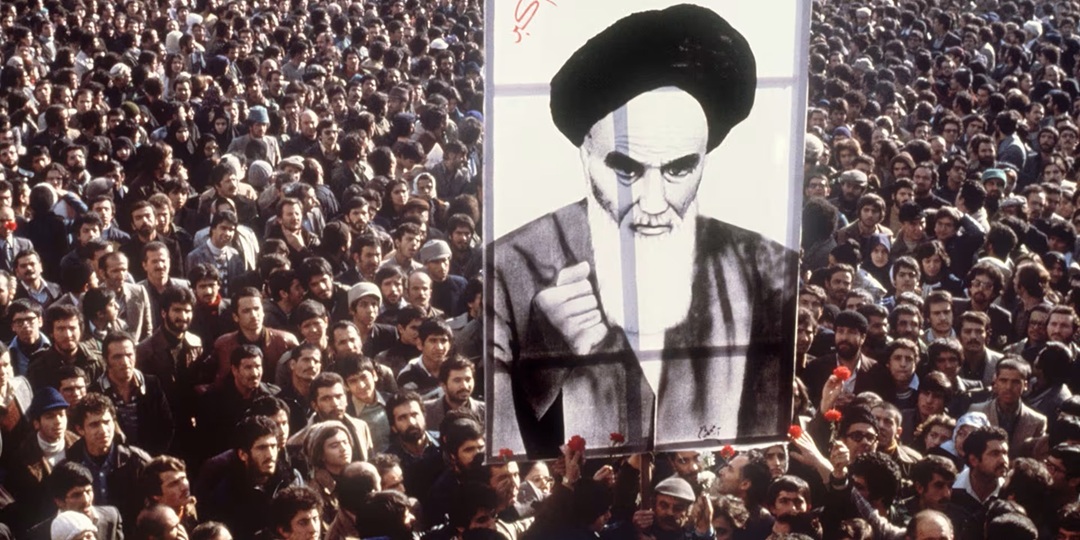

That’s what’s happening in modern Arabic SF – my Egyptian friend was Ahmed Salah Al-Mahdi, but I’d wager the Iranians are a little ahead of us. Modern Iranian literature took up the novel as its primary mode of expression from the early 20th century onwards while we’re still debating, as Arabs, the precedence of the classical Arab poem and the exact definition of the narrative poem (قصيدة النثر).

Farsi poetry has been prose-based since the Shahnameh and Sadegh Hedayat (1903-151), the pioneer of modern Iranian literature, had penned a few SF stories of his own. (The man never was big on realism, something else we haven’t entirely woken up from in Arab literary circles). And he was not averse to traditional storytelling either in his classic strongman epic Dash Akol (1932).

The new rhetoric, whatever that means, refers to dialoguing with yourself over the nature of human motivation, fate, destiny, and the power of social forces, as explicated in modern literary forms. But there’s no reason you can’t blend the old and the new, and science fiction is often the perfect vehicle for that, relying as it does so much on exposition and world-building, not always leaving much room for the individual.

A final note here on what separates us from much Western art. Mr. Iraj wrote this story in response to the racially offensive and historically ridiculous 300 (2006). His response, true to form, was to greet hatred with love. (The story is full of sympathy and humanism, with the detective feeling sorry for the slaughtered Cyrus and even the poor emperor’s horse). He didn’t take the easy route, castigated the ancient Greeks, and belittled their accomplishments. That’s our old-style rhetoric for you!

Emad Aysha is an active member of the Egyptian Society for Science Fiction and most recently coauthored and edited ‘Arab and Muslim Science Fiction: Critical Essays’ published with McFarland in 2022. The term new rhetoric was used by Khaled Gouda Ahmed and Dr. Hosam Elzembely, from the ESSF, to describe Ahmed Al-Mahdi’s ‘The Black Winter,’ with its picturesque graphic violence.A special thank you to Dr. Zahra Jannissari-Landani for introducing me to Mr. Iraj’s work and the growing world of Iranian science fiction.

Brilliant approach

Like the verve and the rich style

Bravooo professor

Here's my website: https://emad-sci-fi.my.canva.site/

Good piece! I enjoyed reading it.