By Emad El-Din Aysha, PhD*

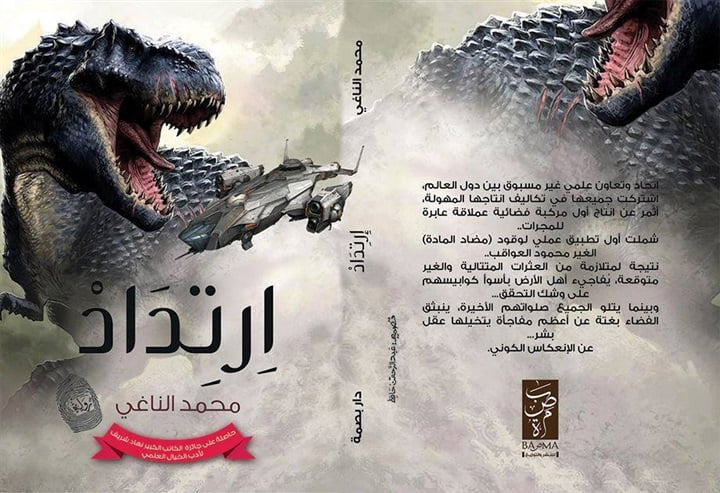

Iritdad or ‘Backwards’ is a science fiction novel by Egyptian author Muhammad Ahmed Al-Nagui, published originally in 2016. As you can probably guess from the title, the novel fits in the time-travel genre.

The story is set in the distant future, 2107 to be specific, and begins with the discovery, by a youthful Egyptian star gazer, of a dark entity making its way towards the solar system. It turns out to be a wormhole and the people in charge of investigating it are the Egyptian space authorities, sending a special shuttle in its path, with a skilled astronaut (Yassin Ismail) and a distinguished physicist (Heba Mansour) on board. But, as luck would have it, the international space agency is launching an incredibly expensive automated space craft at about the same time, and the vehicle finds itself in the path of the dark entity too. The fuel-system of the advanced international craft, however, depends on anti-matter, and if it explodes it could knock Earth off its course towards the blazing inferno of the sun.

Scary stuff, you have to admit! So the denizens of the international space agency send it to the heart of the dark beast, thinking it’s a regular black hole, hoping the explosion will be sucked up by the gravitational sinkhole that a black hole is and spare us all.

The Egyptian spacecraft gets sucked in too, and the pilot, Yassin, wakes up after the cataclysmic explosion to find his ship about to crash in some strange, pristine world with clear blue skies and pure waters. When they find dry land and set the ship down, that’s when the real adventure begins. And I’m glad to say that the story, while not ‘terribly’ original by international standards, does have a distinctively benign Egyptian flavour to it.

The Glide Path of Ages

I have misgivings about this novel, to be frank about it from the word go. I didn’t like the open-ended ending and I couldn’t buy that the international space agency would end up sending out a mission in the path of a dark mass coming towards us, because the Egyptians didn’t bother telling them. It stretches credulity. There are also inconsistencies concerning the nature of the dark entity, as the Adam and Eve duo of Yassin and Heba discuss it afterwards when planning their comeback. There are also mistakes concerning the pre-historic world portrayed here, with well-developed mammalian life coexisting with all the giant reptiles, not to mention the sudden (and near pointless) appearance of Stone Age man towards the end of the story.

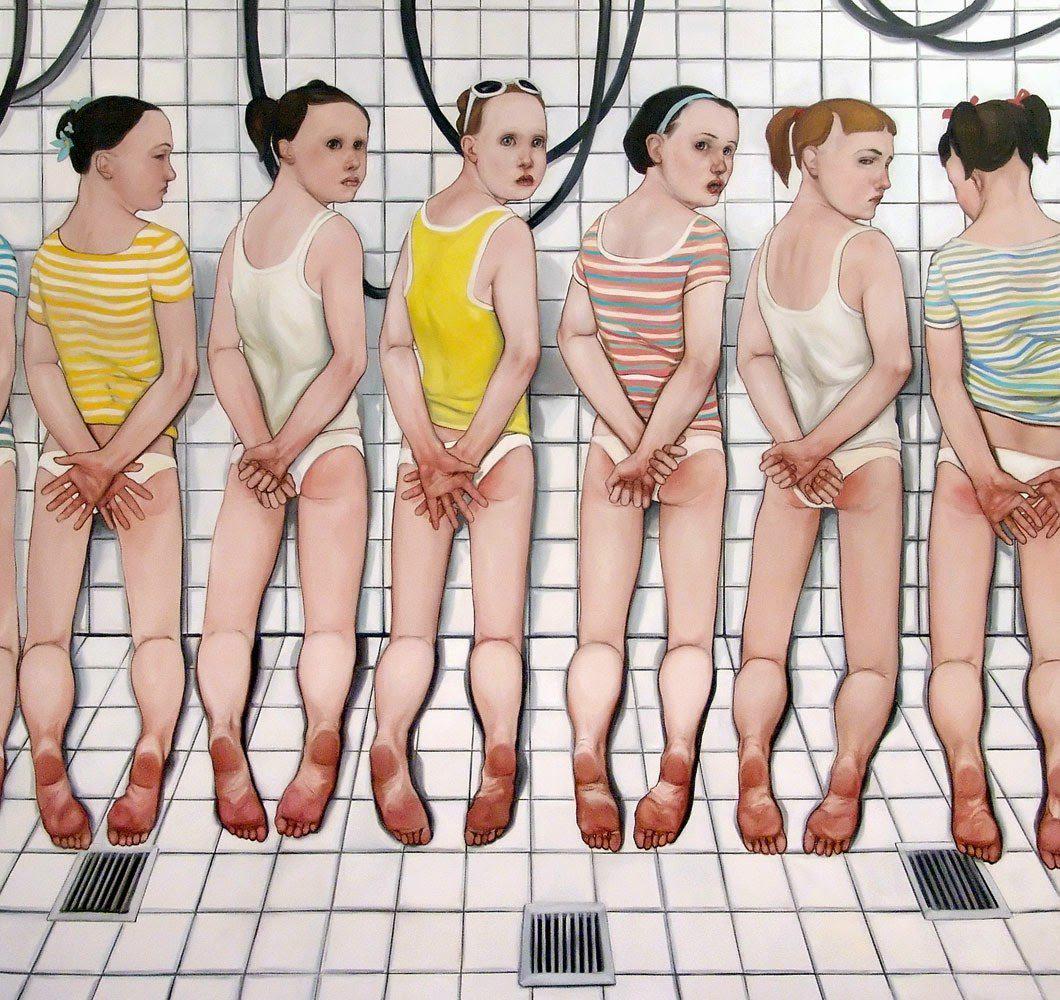

Modern man, with all his gizmos and knowledge, could just barely survive up against the reign of the dinosaurs, let alone cave man. And Yassin and Heba reside in a cave half the time, not that it does them any good up against the more nimble variety of dinosaurs. (Yassin decides it’s safer, for the shuttle, not to stay in it, fearing other humans that might want to control the ship, and continues to think this is a good idea after realising what era he’s living in). When they first land on dry land, they find the world teeming with vegetable life, but no animals, prehistoric or otherwise, only for them to get overwhelmed by the oversized creatures the day after. The only insects you see are bees, and they don’t seem to be overly sized, for some reason.

Still, these numerous mistakes can be forgiven once you place this novel in its appropriate literary context. The novel itself is a modern import in the Arab world, to this day, let alone when it comes to science fiction writers. Authors still haven’t completely digested the concept of the novel, a thoroughly ‘new’ way of doing things in literature and storytelling. Evidence of this literary evolution towards the novel format are strewn all over Irtidad.

Personality quirks are one example of this. Most Arabic SF is written in the ‘novella’ format and so characters are just cardboard cut-outs who do what they’re told, by the all-powerful author, contradictions and tackiness notwithstanding. I wouldn’t go as far as saying that this novel has transcended this problem entirely but the characters have reasonably more depth than is usually the case in Arab SF. Yassin and Heba don’t get along well, at first. He finds her to be a geek and insists that she obey his orders at first, so they can better survive, and they often annoy each other even when they’re on board the spaceship investigating the wormhole. (He’s an astronaut but has special forces training). Closely related to this is the visualisation of the characters.

They’re quite vivid and fit their personalities, making you feel that you’re reading a modern novel. The picturesque settings, particularly the high-tech headquarters of the Egyptian space agency and the international space agency are all very noteworthy, with bright colours and detailed shades and a variety of sparkling ‘things’.

Another positive point here is multiple narrative tracks. You have the Egyptian space programme, and the international space programme, and other individuals chipping in from their various vantage points around the globe as the wormhole makes its way towards Earth, with the giant mechanised spaceship hurtling towards it. This perks up the tension and gives you a panoramic view of life on Earth in this overly technological future, a common technique used in modern thrillers and modern sci-fi, for sure, but not so well known over here.

These narrative tracks reduce themselves into a single track, once Yassin and Heba move backwards in time to the prehistoric past of the Earth, true enough, but it’s a brave attempt on the part of the author nonetheless.

Yet another plus point is how well researched the novel is, again not a common characteristic of Arabic science fiction, or any kind of Arab fiction for that matter. You’re given the scientific names of the dinosaurs in footnotes, in English, along with statements of scientific fact. The explication of the inner workings of black holes and wormholes is impressive, along with the suggestions given by the heroes as to the exact nature of their predicament: they may have gone backwards in time, they may have gone to another planet in the early phases of its history, and they may have gone to earth but in a parallel dimension. They also got the part about electrons disappearing and moving into parallel dimensions right. (It happens as the wormhole approaches, fusing general relativity with quantum mechanics).

And it’s certainly action packed and well-written. Arabic, despite is verboseness, is the perfect language for science fiction, given how descriptive and emotive it is. The scene where they find dry land, you feel like you’re looking at a coral reef, given the incredible menagerie of colours. So, all in all, it’s a worthy contribution to the corpus of Arab and Egyptian sci-fi.

A worthy, if ‘flawed’ contribution.

The Cosmos is a Small Place

You’ll notice in the novel that you have an Egyptian space agency – headquartered (not coincidentally) in the Western desert, which is all green now – and an international space agency, with its primary launching pad in Kazakhstan, taking the place of Cape Canaveral. They also tell you that the new automated vessel they’re launching was paid for in euros. (Heba herself is the head of the physics college at Zewail City, and she’s quite young for the post). The young man who identified the wormhole was in the Egyptian countryside too!

Egyptian and Arab SF, thank heavens, is very cosmopolitan, a great believer in mankind pooling its resources to the benefit of all through space exploration and scientific cooperation. (This predisposition went from the world of fiction to fact when Arabs and Egyptians like Farouk Al-Baz got into NASA, I’ll have you know. Check out my review of Dr. Jörg Matthias Determann’s book Space Science and the Arab World: Astronauts, Observatories and Nationalism in the Middle East, 2018). And now, with the Americans in the can, we don’t have to worry about them fouling things up for us either. There’s only one scene in the whole novel where Americans are mentioned, and more in the coach potato-fashion than anything else. (Some kid watching Saturday Night Live. Do they really still have that show in 2107 AD?)

I’d also wager this thematic is connected with the whole time-travel malarkey. While the author did not succeed in portraying this future world in bad terms, when it comes to pollution, you couldn’t help but notice how pure the world is when they go to prehistory. The air and water specifically. At the same time, the struggle for survival is horrendous. Yassin and Heba almost getting gobbled up and several times by the carnivores, those on four legs and those that fly. If it wasn’t for the two of them helping each other out, they would have perished ages ago. (In one particularly nice scene, Heba falls into a giant Venus fly trap, a plant that devours flesh, seduced by the incredible fragrance of the thing). You ‘feel’ that this incessant competition between the animals, and the plants, is an allusion to the present day world of nation-state and superpower conflict.

Is it a coincidence, I ask you, that Heba insists that they help out a Brachiosaurus? The creature, an incredibly tall herbivore, was attacked by a carnivore and the attacking dinosaur left its claw in the animal’s foot, leaving it bleeding. Yassin pulls the thing out, only to find the foot still bleeding. (The inserted claw was poisonous). So he crushes an eggshell into a fine powder and uses that to stop the bleeding. Later on, when he is attacked and pursued mercilessly by a carnivore, Heba comes to the rescue, with the Brachiosaurus’ help.

That’s stretching it, but in a typically Egyptian way. Egyptians are a very benign lot, when it really comes down to it, something that comes out repeatedly in their science fiction and from the earliest days. The classic example of this, to cite Dr. Mohammad Naguib Matter – an Egyptian SF author himself – is Nihad Sharif’s Number 4 Commands You (1977).[1] Here the advanced race on Mars warns mankind about nuclear war and uses a cloud to wipe people’s memories clean of nuclear science, when those warnings go unheeded. For a slightly more contemporary example we have Dr. Hosam El-Zembely’s The Half-Humans (2001) where two Muslim astronauts race out into the depth of space to help an alien race on the verge of extinction.[2]

Religion is another very Egyptian theme in Irtidad, since Yassin and Heba never hit off, so to speak. They profess their love to each, way at the end of the story when they’re preparing to head back to the future world they came from, but nothing else. (She has skin the colour of wheat and brown hair and he’s a handsome devil on account of his special forces training). Living together in a tent then a cave doesn’t change anything. (So much for close quarter combat). The only thing I thought was a bit too Egyptian about Irtidad was the issue of ‘food’. Yassin gets tired of living off fruits, as delicious and ‘big’ as the fruits are, and begins with fried fish and finally moves on to dinosaur meat and even eggs, despite Heba’s objections over the eggs. (Came in handy in the end, though!)

The Weight of a Genre

Now to get to the not entirely bad but not entirely good stuff either. When things begin to go wrong on Earth, thanks to the giant explosion of the automated vessel in the wormhole, you have assorted scenes from around the globe. One of those scenes involves a passenger on board a plane, a first class passenger, having a delicious fish meal even though he’s not hungry. And his plane is flying towards ‘Palestine’.

Palestine, not Israel. Fine by me, along with this very cosmopolitan future with Zewail City and the Western desert and everything… but!

A very distinguished researcher from Syria, Muhammad El-Yassin, did his MA thesis on Arabic science fiction and something he noted, after an ‘extensive’ survey and analysis of the genre in our part of the world, is that when you get these near-perfect visions of the Arab future, you never have any mention of Israel. It’s as if the country ceased to exist all by itself or was swallowed up by its Arab neighbours. But no explicit mention is made of this.

It’s not a plausible scenario that Arabs unite and progress, if Israel is here dividing them right down the middle. And if they were able to defeat or absorb it, why is no mention made of that explicit fact in these sci-fi works, even if in retrospect? Arab authors, even Arab nationalists, tend to shy away from tackling such topics. (Syrian SF being the one notable exception, relying on Muhammad Al-Yassin). This novel fits into this pattern, I’m sad to say. I really don’t know why nobody in the Arab world wants to tackle these issues head on and come up with a sound and ‘scientific’ strategy for how to deal with the Israelis, even in the word of science fiction. There’s no shortage of confrontations with the Israelis in Arabic spy fiction, in so far as it exists, with Nabil Farouk and also, to a lesser extent, a sci-fi spy mini-series by Muhammad Al-Bidawi.

To hazard a guess I don’t think its fear but more likely a lack of confidence. I say this since many authors who have dealt with the Palestinian cause in their ‘realist’ literature don’t tackle it head on in their occasional forays into science fiction. Realism, at the end of the day, is content with ‘describing’ things as they are, not as they should be, and the really good thing about SF, compared to fantasy, is that it gives you concrete steps to changing that reality, in a sound and reasoned and practicable way.

I was hoping something like that would happen here. Alas, nothing is ever complete. It’s a good novel and headed in the right direction, if not quite hitting the mark. Not so much one step forwards, two steps back. More like three steps forward, one step back. But we’re making progress nonetheless in the footstep game of nations!!

* Emad El-Din Aysha has a PhD in International Studies, from the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom. But he is also a movie reviewer and literary critic, in his past time, and an aspiring author in the Egyptian Society for Science Fiction.

NOTES

[1] This was in 2017 during a presentation of his at the Cultural Salon for the Egyptian Society for Science Fiction. July 17, Nasr City, Egypt.

[2] For a revamped audiobook version please visit https://www.storytel.ae//books/569251-ansf-lbshr?appRedirect=true.