By Emad El-Din Aysha, PhD

Here’s a blast from the past. I remember reading an annoying interview once by the director of Quantum of Solace (2008) where he explained his misplaced sense of realism in the movie, which pissed off a lot of fans, myself included. He said that the original Bond persona dreamed up by Ian Fleming was so invincible and squeaky clean because the novels came out at a time the British were in a state of doubt and weakness. The British Empire was on the rocks in the post-war era, thanks in part to the alliance with the Americans, and there was the Cold War and Communist threat to contend with. It’s the whole ‘losing an empire, searching for a role’ syndrome that has been endemic of British foreign policy, the reverberations of which are still being felt to this day with Brexit.[1]

In Your Darkest Hour

Well, as luck would have it, a friend of mine got me a copy of Adel Nil’s The Espionage Novel in Contemporary Arab Literature (2017). It’s really about the Egyptian spy novel, with an especial focus on Salih Morsi (1929-1996), the main espionage novelist in Egypt and the Arab world. But, more to the point, what did you discover in the folds of this 200 plus page long book? The Egyptian spy novel only kicked in after the 1967 war, and largely as an attempt to give Egyptians faith in themselves following the resounding disaster of that war. And it wasn’t just a military defeat but a giant intelligence failure too. People needed to know, to believe, that we could catch the traitors who had sold out Egyptian and Arabic secrets to the enemy, facilitating their victory in 1967, and also fight back and outsmart the Israelis and beat them at their own game. Look at the parallelism with the British situation. You wouldn’t think that there was something in common with the UK and Egypt, but there is, amazingly enough.

I’d also wager that there is a parallelism even with the American spy novel. The Americans were supremely confident of themselves in the Cold War as far as technological and military superiority were concerned, true enough, but then how do you explain the McCarthyist witch hunts of that era? The Americans may be able to beat the Russians in battle, may be, but how can you fight an enemy you can’t see in a democracy that prides itself on openness and trust? Note that most American espionage literature is not straightforward spy stories, with the human dilemmas facing and intelligence agent busily gathering information on the enemy, but techno-thrillers and usually set out of the Soviet Union itself, either in the Third World or European theatre. Tom Clancy is the classic case, although not my favourite author in this genre. Either that or stories about domestic intelligence and mole hunts or fantastical stories about the Russians invading and occupying the US, forcing people into fighting clandestine wars of resistance. (Read Charles D. Taylor’s wonderful Boomer, about the Soviet’s penetrating the US navy, its nuclear attack subs, or watch Telefon, a Charles Bronson movie where a rogue Russian agent is activating deep penetration agents who have been hypnotised into thinking they are Americans).

This anxiety spilled over into science fiction as well, if not more so. The insects in Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers (1959) are really a stand-in for the communist threat, and with that the whole stand-off between individualism (the American way) and communalism – something you’re pretty much told in the novel. As Fascistic as the military system is in on Earth, the autonomy of the individual is celebrated above all else. UFO and flying saucer mania in the US, celebrated in black and white movies in the 1940s and 50s, was in part a response to the fears of Soviet ‘penetration’ – something that always precedes invasion. (UFO is a military term originally, unidentified flying object, and early post-war paranoia is what led to the ridiculous Project Bluebook. Thank heavens Car Sagan was onboard). And there were many more sci-fi works, movies and stories, with the Soviets invading the US in the aftermath of a nuclear war, than in non-genre literature. Americans were genuinely afraid, despite the expanse and geographic isolation of their country, and their technological and economic superiority. Lyndon Johnson once famously described the US as an ‘island’ nation, meaning that the problems of the world always wash up on its shores. Watch Steven Spielberg, from earlier movies like Jaws to his latter movies like Minority Report, for the island motif. Never mind The Island (2005), let alone Kevin Costner’s Waterworld (1995).

Hence, the paranoia about sleeper cells and sleeper agents that still operates in US popular culture, and politics, to this day. It shows up in proper espionage works, like The Americans and the 24 series, but it’s the artistic representation that is so revealing. You always have a respectable middle class family in a suburban neighbourhood that turn out to be foreign spies or terrorists, and the same anxieties show up in horror (and comedy) movies with the axe murderer or serial killer living next door, or members of some weird religious cult. I’m sure you’ve all watched The 'Burbs (1989) and Disturbia (2007)!

The English, to their considerable credit, have recovered from their initial doubts. Read their spy novels and watch their movies and TV series and you’ll find, towards the end of the 1980s, that they were well aware that the Soviet Union was in decline and the communist threat had abated. They never got swept up in the Reaganite second Cold War, Rambo-mania. (The only American spy author I can think of who resisted that was Robert Ludlum, a champion of détente and scourge of CIA cliques. Then again, he was part English). Watch Smiley’s People and you’ll notice that Karla, when he’s handing himself over, is described as walking with a limp, evidence of having suffered a stroke. Read Ted Allbeury’s The Other Side of Silence, written as far back as 1981, and you have evidence of Soviet economic decline and internal ethnic disunity. And even at the height of the Cold War, the trademark English coldness and sense of fair play and reasonableness held sway. I’m getting this from Jack Higgins novel Solo (1980). In a really snazzy scene you have a British intelligence officer offering a Russian a safe out way out, by faking his death, and he knows full well the guy will cooperate because he’s been living in the West so long he has nothing to go back to in his homeland.

The English, to their considerable credit, have recovered from their initial doubts. Read their spy novels and watch their movies and TV series and you’ll find, towards the end of the 1980s, that they were well aware that the Soviet Union was in decline and the communist threat had abated. They never got swept up in the Reaganite second Cold War, Rambo-mania. (The only American spy author I can think of who resisted that was Robert Ludlum, a champion of détente and scourge of CIA cliques. Then again, he was part English). Watch Smiley’s People and you’ll notice that Karla, when he’s handing himself over, is described as walking with a limp, evidence of having suffered a stroke. Read Ted Allbeury’s The Other Side of Silence, written as far back as 1981, and you have evidence of Soviet economic decline and internal ethnic disunity. And even at the height of the Cold War, the trademark English coldness and sense of fair play and reasonableness held sway. I’m getting this from Jack Higgins novel Solo (1980). In a really snazzy scene you have a British intelligence officer offering a Russian a safe out way out, by faking his death, and he knows full well the guy will cooperate because he’s been living in the West so long he has nothing to go back to in his homeland.

That’s another characteristic of James Bond movies, at least until the Americans took over. Portraying the enemy as human and so someone who can be negotiated with, unlike the ideological fanatics you see in American Cold War drama – in The Hunt for Red October (1984), a KGB agent is trying to blow up the submarine and ‘smiles’ while doing it. (Watch The Patriot and you'll find the redcoats depicted essentially in the same way). All hail Britannia!

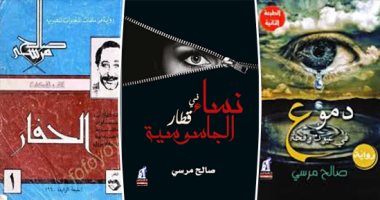

The Science of the Afterlife

Spy novels, then, are a giant confidence game, and not just in Third World countries that have been defeated technologically and militarily. That would explain, in part, why they have persisted in Egypt, even after the Camp David peace accords. There aren’t any serious novels anymore, on the model of Salih Morsi’s Rafaat Al-Hagan and Al-Hafar, sadly, but there are advantages to this since, as Nil argues, the successful novels were all based on true stories whereas the genuinely fictional works failed dismally (pp. 38-40). Since then, however, the genre has moved underground as it were into the completely fictional realm of the pulps, pioneered by Nabil Farouk’s pocketbook series Ragul Al-Mustahil/The Impossible Man (pp. 33-35). Not to forget the Qanas A-Muhtarif/Professional Sniper series, which I personally like more. (It doesn’t get mentioned in Nil’s book to my knowledge).

This may be a notch down from the past, but it portends of good things, and for more than one reason. Pocketbooks and pulp fiction means a wider audience, particularly among young people who will grow up to demand more as time goes by; and they are, if you look at the bookshelves and street vendors of books. There’s lots of adventure series, spy series books out there. The pulps, moreover, is what kept science fiction alive in the West, in the aftermath of Verne and Wells, and it has already kept science fiction alive here in Egypt over the 1990s thanks again to Nabil Farouk and Ahmed Khaled Tawfik. Secondly, pulp fiction is the logical refuge for spy literature here in Egypt and the Arab world, if only because the critics refuse to take it seriously, a key point in Nil’s book (pp. 63-68).

Again, this is a problem that has afflicted Arabic science fiction and for the longest time, which is one of the reasonable that it had to go underground to stay alive. But, with time, Arab SF has slowly turned the tables on the critical establishment and its getting increasingly recognised by the Writer’s Union here in Egypt. Finally, the pocketbook spy genre is useful for another reason. It’s finding common cause with, and fusing with, science fiction.

I say this because of the novels of Muhammad Al-Bidewi, a time-travel series of four novels, which are a clear hybrid of the Egyptian pulp spy novel with Arabic science fiction. Sadly I’ve only reads books two and three, Treacherous Sands and The Dam of Death, so have no idea how the hero Shihab can travel back and forth through time. (I bought the books second-hand and the publisher didn’t have any details about the storyline). Treacherous Sands is more retrospective, dealing with the horrendous mistakes made by the Egyptian regime in the run up to the 1967 war. More specifically the hero tries to foil the Israeli plot to kill off the German rocket scientists working in Egypt at the time, only for us to discover that an Egyptian engineer has produced a better missile system, which infuriates the Soviets who want to force Egypt into relying on its scuds. The hero succeeds in launching the Egyptian-made missiles at the Israeli airfields, preventing the war from happening and with that the massacre of Egyptian POWs, but the fate of Palestine doesn’t change and Israel continues to exist. Depressing, but also quite believable.

The Dam of Death is more science fictiony. The opening sequence has a harrowing portrayal of a future Egypt that has become a giant desert, with special military escorts for that most valuable of commodities – water. Not that it does them any good. The water mafia slaughters the soldiers and steals the water for itself to extort more money out of Egypt. And why all this? Because of the Renaissance dam built in Ethiopia, with Israeli and American help. The hero in this story goes backwards in time – still in the future relative to us, the readers – and destroys the dam while it’s still under construction, after penetrating the operation, disguising himself as an American investor. To make matters even more futuristic, two agents from the future – time cops, essentially – come after him. They almost ruin his plans and it takes all of his wits to escape. The level of action and plot twists owes a great deal to Ragul Al-Mustahil, and the Professional Sniper as well if you ask me, but there lots of ‘science’ deployed in the story too that’s all from Muhammad Al-Bidewi. There’s a scene where the Israelis are in hot pursuit, tracking the hero’s movements using his heat signature, and Shihab lights up fires in the brush to elude the scanners.

So, a worthy contribution both to the corpus of Arabic science fiction and the Egyptian spy novel. It may seem odd that SF would be paired up with the espionage thriller, but it isn’t. We saw above the parallelism of spy fiction and SF during the Cold War and how both gave vent to anxieties operating behind the psychological scenes, articulating them in concrete form through imagined threats and characters, dialogue and plotlines. But the relationship between the two genres goes deeper than that. Intelligence isn’t just about gathering data on an enemy but imagining up worst case scenarios and means of countering them. And what branch of fiction better than SF and ‘speculative’ fiction to dream up such scenarios? Just look at the Dam of Death, a warning call to people in the present about what could happen in the future if the right steps aren’t taken to secure the country’s water security. Nobody in American intelligence, the alphabet soup of agencies they have, could have dreamed up September 11, and they had to get Tom Clancy on CNN to comment on the plane crashes, since he was the only one with a novel where a plane crashes into the White House kills off the president.

I remember watching Arab commentators, Egyptians, straight after the event saying if you watched American SF movies, like Independence Day, that came out towards the end of the 20th century, you noticed the theme of confrontation and destruction from some unknown threat. Portending that the Americans themselves secretly suspected somebody was out to get them. I can add here a little known Tom Clancy SF novel, Ruthless.com, where certain powers in East Asia cooperate in a diabolical plot against the US, in revenge for the 1998 financial crisis that destroyed the East Asian economic miracle. Blowback, in other words, and that’s precisely what the experts said about 9/11.

So, if anything, SF is one step ahead of the spy novel in predicting things that could, and often do go wrong. Most of what Tom Clancy has been writing since 9/11 is science fiction, in point of fact, and quite a few spy novelists have dabbled in SF in the past. Len Deighton wrote SS-GB (1978), an alternate history novel where the Germans successfully invade-occupy Britain during the Second World War – now made into a stunning TV series. (I read the novel in the early 1990s when I was in Egypt, again from a used-books seller). Deighton’s written a number of borderline SF-spy novels too, like Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Spy (1976) and The Billion Dollar Brain (1966); check out Edward S. Aarons’ Assignment Moon Girl (Sam Durell #26).[2] The same goes for many, many James Bond movies, with floating space stations or underwater cities, things that don’t exist at the moment but are just around the corner, like most of the spy gadgets James Bond himself uses.

So, if anything, SF is one step ahead of the spy novel in predicting things that could, and often do go wrong. Most of what Tom Clancy has been writing since 9/11 is science fiction, in point of fact, and quite a few spy novelists have dabbled in SF in the past. Len Deighton wrote SS-GB (1978), an alternate history novel where the Germans successfully invade-occupy Britain during the Second World War – now made into a stunning TV series. (I read the novel in the early 1990s when I was in Egypt, again from a used-books seller). Deighton’s written a number of borderline SF-spy novels too, like Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Spy (1976) and The Billion Dollar Brain (1966); check out Edward S. Aarons’ Assignment Moon Girl (Sam Durell #26).[2] The same goes for many, many James Bond movies, with floating space stations or underwater cities, things that don’t exist at the moment but are just around the corner, like most of the spy gadgets James Bond himself uses.

SF and the espionage thriller, then, overlap and at more than one level, making Arabic science fiction the perfect vehicle both to revive the spy genre locally, and to upgrade and perfect it too. Now to take a slightly different look at things, and rely on something other than second-hand books. Namely, downloadable movies!

In the Hallway, with the Mirrors

A good quality avi movie, I insist, and therefore not second-hand. In this case, Bruce Lee’s Fist of Fury circa 1972. It seems an odd movie to mention in light of the subject matter of this article but it isn’t. The storyline is set during the Japanese ‘presence’ in China, I think before the Second World War and direct occupation of China, in a period of time when the European powers dominated the country. (It seems almost unimaginable, given the status of China today but, then again, that’s the whole point). A Japanese karate school intrudes on a funeral for a Chinese kung fu master, who died under suspicious circumstances, and they parade a sign saying that China is the ‘sick man of East Asia’ and they challenge them to fight back. Bruce Lee, dressed inexplicably in white, almost loses his cool but his colleagues (dressed in black) restrain him. Later he goes to the karate school and beats everybody up, singlehanded, and quite convincingly too given how fast and intense he is. But that’s not the end of the story. The Japanese retaliate at the Chinese school, and then get the authorities to try and shut the place down. Bruce Lee learns that his master was poisoned, by the envious Japanese, and takes his revenge and all by himself, without involving his teammates. It has a bad effect on his love life, his marriage plans, and gets many of his friends killed in the end. But, interestingly enough, he doesn’t rush into things this time. He spies on his opponents, pretending to be a repairman from the telephone service, among other things.

In the closing scene you have the remaining classmates (dressed in grey) admitting they were wrong, to think the law (read, international law) could protect them. At the same time Bruce Lee hands himself over to the authorities, so his school isn’t shut down, only to find foreigners getting ready to shoot him down, and he leaps into action in the closing scene.

Several conclusions can be drawn from this. For one Kung Fu movies, it seems, are very much like spy novels in the Egyptian, British and American traditions. They are there to reassure people in to face of an overwhelming enemy. Secondly, the Chinese don’t think in a dualistic, black-white way. You could see that in the colours on display juxtaposed to the consequences of Bruce Lee’s actions. He gets innocent people killed through his rashness and misplaced sense of individualism but, at the same time, he is canny and outsmarts his opponents and his colleagues themselves learn that they should have stuck with him from the very beginning. Lying low is one thing, actively cooperating with the enemy and handing over one of your own kind is another.

The mental and moral consequences can be seen in the scene where Bruce Lee is speaking to his sweetheart. She catches him gobbling away on something he cooked out in the wilderness. It looks like a large lizard and he’s eating it without a chopstick in sight.

The final lesson as far as we are concerned here in the Arab world is the need to study and know your enemy, thoroughly. That’s the job of the spy novel, and literature more generally. That’s the job of intelligence too, enemy intentions and mindset and capabilities and secret plans. War, before its a shooting war, is a war of spies and eavesdropping and leaks and subterfuge. You need to know where the enemy is hiding before you can shoot at him, after all. And being overly self-confident of your abilities and the virtue of your cause can actually be debilitating, tricking you into not studying your opponent, thinking that he deserves to lose and so will inevitably lose. Even somebody nicknamed the ‘fist of fury’, because of his uncontrollable temper, didn’t make that mistake.

So as not to stick to Arabs too much, something I am prone at doing, we have the example of the Americans in Vietnam. To cite sociologist James William Gibson, and not a political scientist, the American side refused to see communism as a rival political system and ideology that could be learned from and appreciated, seeing it as monolithic, alien and otherwordly. They insisted that the American way was the only way – their values of free enterprise and individualism and rationalism were naturally ordained and so could not be wrong.[3] Worse still, they didn’t study Vietnamese history and so missed the fact that Vietnamese had done nothing throughout their whole history except resist foreign invasions, no matter the odds. And then even worse that, if I can add a literary twist to the tale here, they became their enemy.

I say this, again, because of Heinlein’s Starship Troopers, portraying the Communist enemy as like an insect, something with no individual volition or autonomy. Well, James William Gibson explains that the whole system of warfare the Americans pursued in Vietnam, what he calls technowar, was grounded in the ‘limited war’ doctrine pushed by Henry Kissinger and the Pentagon in the 1950s, which was to avoid a direct and nuclear confrontation with the Soviets and fight in the Third World instead, and win by outspending and out-producing the piss poor Third world country in question. In the process they rephrased their whole military logic, making officers into production managers that treated their soldiers like factory line workers, quite literally mindless automatons. So much so in fact that they repeated the same mistakes over and over again, like a mindless robot in a factory doing the same work routine, allowing the enemy to predict their moves. They were so technological confident in fact that they used unencrypted radio transmissions in the field, which the Vietcong could listen in on by buying American radio-sets off the black market!

I say this, again, because of Heinlein’s Starship Troopers, portraying the Communist enemy as like an insect, something with no individual volition or autonomy. Well, James William Gibson explains that the whole system of warfare the Americans pursued in Vietnam, what he calls technowar, was grounded in the ‘limited war’ doctrine pushed by Henry Kissinger and the Pentagon in the 1950s, which was to avoid a direct and nuclear confrontation with the Soviets and fight in the Third World instead, and win by outspending and out-producing the piss poor Third world country in question. In the process they rephrased their whole military logic, making officers into production managers that treated their soldiers like factory line workers, quite literally mindless automatons. So much so in fact that they repeated the same mistakes over and over again, like a mindless robot in a factory doing the same work routine, allowing the enemy to predict their moves. They were so technological confident in fact that they used unencrypted radio transmissions in the field, which the Vietcong could listen in on by buying American radio-sets off the black market!

So, it’s good not to go into a war blind, and do a little groundwork beforehand through spying and familiarising yourself with the cultural terrain first. In the case of the Arabs, our spies in Israel, chief among them Rafaat Al-Hagan, understood the enemy perfectly, becoming one of them on the outside till they trusted him with their deepest secrets. The problem was, as usual, politics. The regime at the time didn’t make the best of his breakthroughs, and not only had he learned of the plans for the 1967 war but the Suez 1956 war too. (Pretty much like what you see in Treacherous Sands, to be honest). Now that heavy duty spy novels have gone into a tailspin, it’s up to pocketbook authors and us sci-fi buffs to fill the breach.

Movies like Al-Mamar are a first step in that direction and will no doubt boost sales for patriotic fiction and other works of art. A second step, of course, is the curious but exciting hybrid of spy-science fiction novels. The third step would be to make SF action-espionage movies, or any kind of SF movie, with all its ‘empowering’ effects.

Although a multiple shades of grey kung fu movie or two wouldn’t hurt in the meantime!!

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to El-Mubarak Saleh and Ahmed Al-Mahdi.

[1] The quote is from Secretary of State Dean Acheson, in the 1950s. It was also the title of a famous book we used at university in England!

[2] John Gardner even did a borderline ‘paranormal’ spy novel, The Werewolf Trace (1977), believe it or not!

[3] Please see his 1987 interview with Frank Marrow and Doug Kellner of Alternative Views, “The Perfect War: Technowar in VIETNAM (1987)”, parts I and II.