By Emad El-Din Aysha, PhD

I had the good fortune of attending a book signing event once, with Ibrahim Nasrallah as the guest of honour, and during the question-answer session, somebody mentioned George Orwell’s dystopian classic 1984. This was no coincidence since the book being signed away was Nasrallah’s own semi-dystopian novel The Second War of the Dog. (This was on 23 November 2018 at Tanmia Bookstores, with Sudanese author Hamour Ziyadah doing the introducing). He surprised us all, however, with his response. He agreed that the overwhelming power of the state is evident in Orwell’s novel, as the questioner correctly pointed out.

Nonetheless, we as Arabs know better, Nasrallah insisted. We have more experience with tyrannical regimes in our history than Westerners do and so we know that a regime, no matter how tyrannical and seemingly all-powerful, will eventually fall apart and be overthrown. Often it is overthrown by another totalitarian group, but that itself is indicative that the state is never as powerful as it thinks it is, even with its control over information and people’s livelihoods. I was overjoyed to hear his, since something I didn’t like about Orwell’s novel – I read it at school – was this notion that everything in Oceania was inefficient, except for the Thought Police. That didn’t sound right to me, even back then. The inefficiency would seep into everything, including the goon squads, grounded as it is in bureaucracy and corruption and budgetary problems and nepotism, etc.

Dystopia, it seems, is a kind of luxury in the Western world, much like horror. People are so scared out of their wits in this part of the world, with real-life anxieties around every corner, that they don’t need to make movies about serial killers or vampires to freak themselves out.

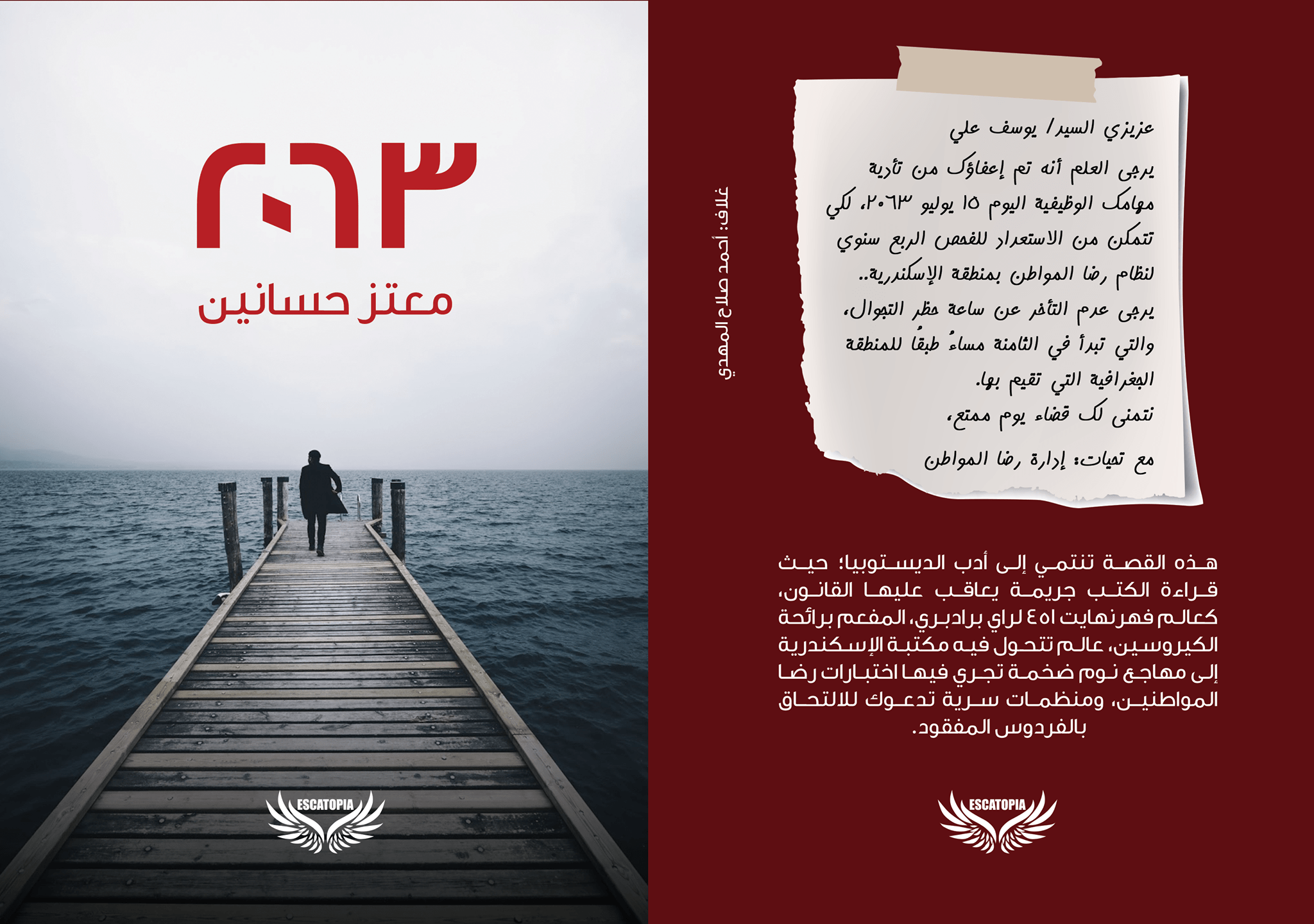

It’s a productive enterprise, writing dystopia wherever you happen to live, helping highlight at what is wrong – or could go wrong – with the world you live in, but a healthy dose of realism is always called for too. I mention all this on account of a nifty little article by Khaled Gouda Ahmed on a very contemporary example of Arab dystopian literature. The article was has just been published, this month of this new year, about a novella penned by a friend of mine way back in 2016 – Moataz Hassanien’s 2063, the subject of this admittedly long overdue book review of mine!

Satisfaction Guaranteed

Khaled Gouda does a much better job on the narrative mystique of the novella than I can possibly hope to do here so I’ll focus on the themes and lessons to be learned instead – and the humour, which is upliftingly Egyptian. 2063 opens up avenues for research into utopia-dystopian literature, gauging how Arabs and Muslims understand these notions, at variance with the well-established Western tradition. The novella is a grim tale about a young man residing in Egypt in the year 2063, Yousef Ali, but it’s not too grim. There’s light at the end of the tunnel and the badness of the world the hero lives in is not exclusively political or imposed on us from abroad. In this future world Egypt resides under a foreign military occupation – the TAMDA alliance, modelled on NATO – where people are actually ‘happy’, because they have secure jobs and provisions and have ample access to drugs, alcohol and sex.

The only catch is that you have to take a citizen satisfaction test to see just happy you are, and if you fall to 95% satisfaction, they put you to sleep. Yousef, as a nominal hero, is satisfied with his lot in life, having all the material amenities and sense of security most young people crave for in the Arab world. The only thing bugging him is the memory of his father’s suicide. He wakes up every day, hearing the gun shot that ended his father’s life. The father in question was a revolutionary who had enjoyed, very briefly, the Arab Spring, only to find a military junta taking over and the country sinking into debt and the new leadership class handing over the country to the TAMDA alliance. When the young protest a second time, downtown Cairo get’s nuked, and TAMDA forces take over anyway. But all that was in the distant past. The young revolutionaries have all died out, from old age or cancer (or suicide), and Yousef’s generation has taken over. And they’re as happy as can be, having witnessed the country recover economically – all the debts paid off – while the TAMDA regime provides them with all the amenities of life, in exchange for non-stop surveillance and walled-in neighbourhoods and the outlawing of books.

Yousef’s commentary on this way of living is: “That’s what made us different from my father’s generation. This is our country, but it was never theirs.” He’s the classic anti-hero, true enough, but there’s more to it than that. Winston Smith in 1984 can’t decide whether he likes the world he lives in or not because he doesn’t have access to the complete picture. He suspects the world is bad, but is afraid that he might be wrong, be mad, because the average worker is better off than ever before and he doesn’t know exactly how the party came to power and Big Brother was invented. The past has been expunged and so his cognitive faculties aren’t working properly, despite how loathsome life is. Endless shortages in food and other services, even razorblades, the cold and the grime and the fear of being denounced and having your identity rubbed out, and the chastity regulations meant to discourage sex and love, even within the household.

Not so with our Egyptian protagonist. Yousef remembers everything perfectly, having read his father’s banned books as a kid and on account of his father’s own story. He just doesn’t care. His priorities are clear in life, and they are not so different from the real-world concerns of Arabs. Oh, he still has all the books, bribing the local building inspector to look the other way. Inefficiency, like I said, and Yousef was quite pleased to discover his father was able to get away with this and for so long.

This is a far more realistic portrayal of totalitarianism, again, and you will notice the difference when it comes to sex and romance. Everything is allowed for the Egyptians residing under the TAMDA occupation and people are meant to be happy, quantitatively. Moataz is relying on first-hand knowledge since everything from hashish to belly dancing has been deployed in Egyptian history, from the time of the Fatimids to Abdel Nasser. (On the day before the 1967 War, soldiers were given pictures of movie starlets and belly dancers to get their spirits up, and I don’t remember the Muslim Brothers banning any of this when they came to power). Orwell, it seems, was trying too hard, trying to imagine what such a regime would do, how it would work and buy off the masses.

Another important departure point between Arab and Western dystopias is the issue of social bonds, family life verses individualism. Yousef Ali, despite his wholehearted acceptance of the world he is living in, is not as happy as he should be. His test scores have been slipping for some time now and when he heads off to the citizen satisfaction centre in his home town of Alexandria, he’s fairly certain he won’t survive this time around. (The Bibliotheca Alexandria is emptied of its books and made into the local centre to put potential troublemakers to sleep, and the residents can’t see the Mediterranean anymore, thanks to the walls). The reason is his sense of loneliness. Sex is not the same thing as love, not the same thing as having someone special in your life that loves you back, and bringing children into the world and feeling whole.

Do you see any such sentiments on display in Orwell’s 1984, brilliant novel that it was? Not likely. The West is afflicted with individualism and doesn’t think in these terms. It sees freedom as a confrontation between the individual and the state, or society. Hence, the sexual bans and chastity leagues.

We have different priorities, as said before, and a different set of real-world experiences. And Yousef is also plagued by the memory of his father, and his father’s books, all that heritage he has cut himself off from. He can’t relate to his father’s example and that makes him feel out of place in this world. Alienation in the Arab way of thinking is not being isolated from society, as Westerners think, but being overly integrated into society and its norms to the point that you forget yourself. This is terrible, I know, but it also makes more sense. The ultimate in alienation is not knowing that you’re alienated and thinking that it’s everyone else who’s mentally ill, not yours truly.

Strike one for Arab authors versus the Western variety. Or is that two or three, or four?

A Context in the Making

Yousef then heads off to the satisfaction centre knowing he might not come back without a second thought, and doesn’t even mind that you can’t see the sea anymore because Alexandria is walled in. you don’t need a reminder of freedom, since there is nowhere to go anyway. If he became an illegal migrant, the Europeans would dump him back here, one of the whole reasons the military alliance occupied Egypt to begin with (we are told).

Fortunately, when he fails his examination, a sympathetic employee there lets him go – a girl of course, named Heba Ismail – and goes on the run with him. In the process he puts his fanciful notions of happiness to the test when he hides out at the ‘Paradise Club’. This is a gang that makes people happy, in exchange for all their life savings, and one of their roving delegates had bumped into Yousef just before he went into the ex-library. The gang give him and Heba comfy, roomy lodgings and even fetch his father’s books for him, for a down payment. At first everything is okay, but with time both Yousef and Heba get agitated from doing nothing all day long excerpt eat, sleep and watch TV. (Sounds disturbingly familiar, don’t you think?) The Paradise Club is meant to be a mirror-image of the society topside, exposing its limitations. (I’d suspected as much on my first reading but confirmed it in conversation with Moataz).

Notice also that the relationship between the dynamic duo remains ‘innocent’. They never do anything while they’re in their motel room, so to speak. It seems they’ve put their relationship on hold, getting married and falling in love and having a happy family. It’s a bit artificial but it hammers home the message about what we, as Arabs and Muslims, consider happiness to be and what we consider to be a dystopia – a false utopia that doesn’t allow for these more substantive pleasures and freedoms.

Then the authorities find out about the Paradise Club and the gang has to clear everybody out. That’s when Yousef and Heba start getting happy, having put the fake life they were living behind them and getting out into the open. They take a train on an old, deserted rail-line in the Western desert and trust their fate to the unknown. All they have is each other and their hopes and dreams, and, oh, Yousef’s book collection. Sounds like more than enough to create a new world, if you ask me!

It’s good that 2063 ends on a positive note, which is more than I can say for most dystopian novels, East and West. Still, that itself is indicative of something happening behind the scenes, in the hearts and minds and souls of authors everywhere in the Arab world. Not only are they defying doom and gloom, they’re also devising their own distinct brand of dystopian literature.

Dystopian novels are rare in Arabic literary history, despite all our grim real-life experiences. When dystopian novels were penned in the past, they were often in blatant imitation of what the West had to offer. And even then they didn’t work, stapling two inconsistent sets of cultural precepts together. Sabri Musa’s The Master from the Spinach Field (1987), for instance, is usually taken as the classic dystopian Arab SF text. You have a world of pleasure and endless holidays and sex and drugs, and no family life, much like Moataz Hassanien’s 2063, but the format for the novel seems to come from outside the Arab fold entirely. The city with the crystalline dome protecting the residents from the radiation and pollution of a destroyed future world seems to be taken from inspired by Yevgeny Zamyatin’s dystopian classic We (1924), along with much of the plotline, only to have a forced scene where the two rebels extol the virtues of marriage and monogamy to the distracted masses. There’s nothing wrong with that, as such, but it’s done in a very top down and unconvincing way. There’s no real dialogue and debate of opinions, so its feels out of place with the surroundings and the plot. It feels like propaganda, and nothing more. (Please see Muhammad Al-Yassin’s 2008 MA thesis, Science Fiction in Contemporary Arabic Literature, in Light of Comparative Studies[Arabic], Al-Baath University, Homs, Syria).

Moataz Hassanien’s novella, however, is thoroughly homegrown, while digesting everything that went on before. In the preface to his book the young author mentions other dystopian novels like Otared (2013) by Mohammed Rabie, and in the story itself the hero mentions Albert Camus’ novel The Stranger. Moataz is clearly a well read person, and doesn’t hide the sources of his research and inspirations. And the fact that novels like Otared and The Queue (2014) by Basma Abd Al-Aziz have started coming out since 2011, is evidence that both the writers and the readers in Egypt and at the Arab world at large at ‘maturing’ and fast. Not to forget the man who got the ball rolling beforehand, the dearly departed Ahmed Khaled Tawfik and his novels Like Icarus, In the Tunnel with the Rats and Utopia.

There’s plenty of drugs, alcohol and sex in several of these dystopia experiments too and, to be fair to Orwell, even he outlines how the (vodka-like) cheap synthetic gin is used to placate the outer party while porn is used to control the proles. (Not to forget promiscuity, sex-hormone chewing gun and soma in Huxely’s Brave New World). But Arab authors use these tools more consistently I’m glad to say, and having a family and roots as a humanising and de-alienating is very distinct thematic contribution on our part as well. With a couple of notable exceptions.

On the topic of that exception, speaking to a Sudanese friend from Sabri Musa’s generation, I learned the author was a big fan of Nasserist socialism in its heyday and helped promote it. Only to switch sides entirely when Sadat came into office and started freeing up the economy. Hmmm!

One Step Forward, Two…

Well, such political chicanery is not exclusive to the Arab world, I’m gladly sad to say. Getting Moataz’s book recognised was an uphill task, not just here but abroad. He’d originally written it in 2016, and has been struggling to get it published ever since. Printing presses here wouldn’t touch it with a ten foot pole. If it wasn’t for Ahmed Salah Al-Mahdi helping him out, as a friend, it wouldn’t have hit the bookshelves through the Escatopia publishing imprint. (Escatopia is an Egyptian speculative fiction magazine of sorts, on facebook managed by a dedicated band of friends led by Ahmed Al-Mahdi). From there a cultural salon was held in the book’s honour by the Egyptian Society for Science Fiction (on 27 April 2018). But little has been heard of the work since then, till Khaled Gouda’s aforementioned article came out. And I can add an extra twist to the tale here too. I’d translated a portion of the novella to English in a half-baked attempt to get it recognised internationally, and I even approached a newly founded online magazine that specialises in outlawed texts.

Dystopia was right up their ally and, despite the fact that they liked the translation and the original text, they refused to publish it. And it took them months and months to make a final decision, even though the journal was a voluntary platform. Nobody was going to get paid, either Moataz or me. I’ve tried repeatedly with other speculative fiction outlets, only to get rebuffed in the end and after too long a wait. And as if that wasn’t bad enough, these other publications were from the Third World and dedicated to familiarising the world with the plight of the unwashed masses.

It seems some parts of the developing world have priority over others. Or, as Orwell would put it, all animals are equal but some are more equal than other…!!!!

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Ahmed Al-Mahdi for both introducing me to Moataz Hassanien and to the burgeoning Egyptian dystopian genre.