A harrowing 4-day exhibition on Egypt’s digital transformation, which I had the honour of attending. The Cairo ICT 2025, sponsored by the government, no less.

By Emad Aysha

Typically, I avoided the big talk panel discussions and focused on the micro details among the exhibitionists. I discerned, to my own amazement, some positive transformations taking place in the nooks and crannies of Egypt’s exhausted educational landscape.

Three approaches seem to be converging on us, in some cases without our even being aware. But in all cases, they portend well. The first approach comes from China.

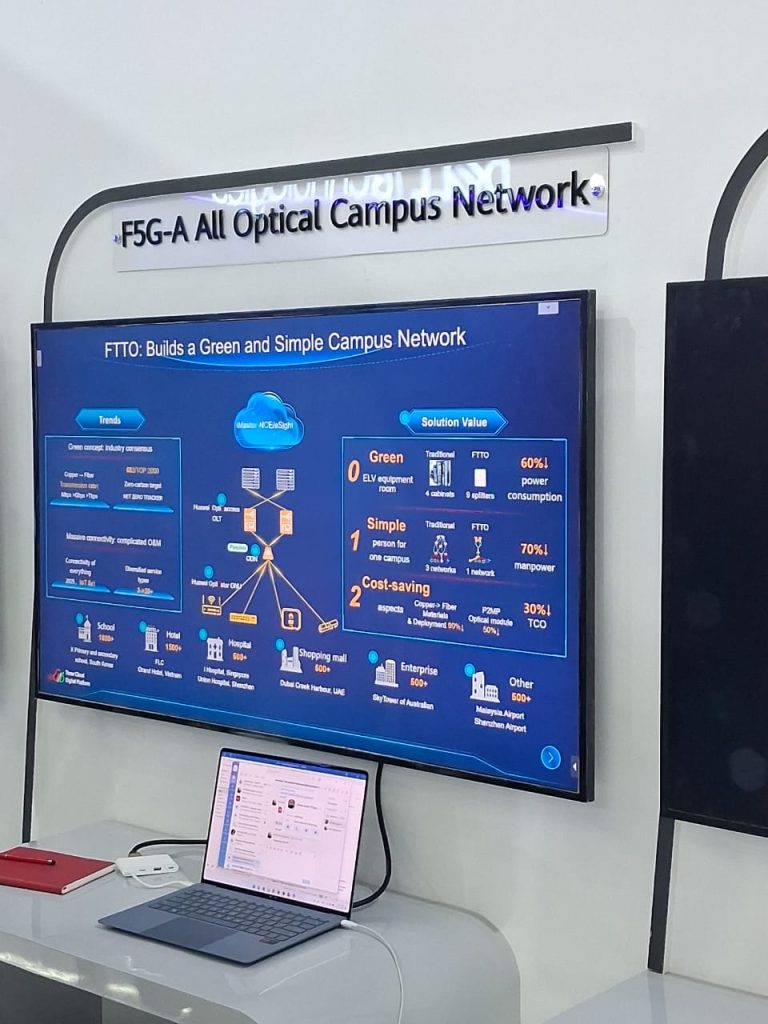

This is a country that doesn’t content itself with classroom advancements with smartboards, but also with campus-wide management of the ins and outs of education via AI. Endless electronics in an individual classroom, let alone a building full of classrooms, mean bugs in the system and power-outage problems.

Not to mention naughty students cheating on their exam papers while the teacher is stuck drawing away on the smartboard. Cameras, switchboards, and consoles all need to be monitored in tandem, and that means an all-seeing eye, a computer system that can track anomalies and fix them in real-time.

I found this all out at the Huawei stand, foolishly thinking they’d have mobile phones on display.

COMMAND & CONTROL: The campus of tomorrow today at the Huawei stand, promising us a cheat-free, energy efficient education. [All event photos taken on my smartphone]

The second approach comes from India, from a multipurpose company called Manage Engine. They had educational applications, so I had to ask.

The engineer assigned to me, a lovely young lady, explained that having tablets in the classroom is both a boon and a burden. You need to be sure nobody is playing computer games, that kids are not checking out ‘amoral’ websites, never mind trading exam papers or wasting their time on social media sites that will corrupt their brains with conspiracy theories.

A little electronic eavesdropping never hurt, and they have an inbuilt ‘agent’ on classroom computers to monitor internet activity, with restrictions that nonetheless allow kids to browse for knowledge. Not to mention managing everything to avoid system blocks, overloads, or hacking.

That’s great, of course, in India, but what’s it got to do with us? Notoriously, when tablets were introduced in the classroom, kids began playing games on them. Well, turns out this company has Egyptian clients, so there's growing awareness that software solutions can pave the way for hardware to do its thing.

I would have thought that educators and decision-makers would have given up. Seems not, at least in the private sector. So there’s hope still if this bold experiment cascades into a nationwide project.

The third approach, and this will surprise you, comes directly from Egypt itself. I chanced upon the College of Artificial Intelligence in Alamein at the exhibition. There is only one other AI university in Egypt, and this one has been running since 2019.

One of their innovations was a Voice Assistant, a small blue box that could repeat lessons and answer questions; a teaching assistant in the palm of your hand. It’s their own patented invention, dirt cheap, easy to power, and will no doubt advance into something even smaller, like a pen.

They also had an AI robot there to introduce the place, a self-driving car, and other gizmos from companies and projects they were partnered with. More impressive still was their educational curriculum, which included topics such as 'deep learning' and 'swarm intelligence', over four long academic years.

The staff were enthusiastic, punctual and full of ideas, and special thanks to Ahmed Mohamed Metwalli and Mohamed Elsayed, engineers and academics at the same time. I also got the chance to pitch them an idea: getting universities like theirs to sponsor sci-fi contests.

LEARNING CURVE: Ahmed Mohamed Metwalli [middle] next to the aforementioned robot that greeted me with a song and dance routine. The little blue box in his hand is the Voice Assistant.

University English departments in the West do this all the time, with their own specialised publications – magazines or blogs – and even the European Space Agency once sponsored an international short story contest.

What better way to create a whole new generation of scientists and technicians and AI enthusiasts who ‘think outside the box’ than science fiction? That’s the entire development plan of the Chinese, as we were told in Worldcon in Chengdu, 2023.

Fiction becomes fact specifically in the world of science and invention. One of the pioneers of robotics in America was a fan of Isaac Asimov’s robot stories, and specifically of their time together at university.

Asimov himself was amazed to find an op-ed praising him for having anticipated the mechanics of the flash drive. The concepts of escape velocity and multiphase rockets, which are so essential to the space programme, were devised initially by none other than Jules Verne.

A boyhood fan of Verne was the man who later calculated the exact figure of escape velocity. Mobile phones were anticipated in Star Trek as far back as the 1960s, along with flat-screen displays and tablets in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

One of the engineers who pioneered the Commodore PC was actually inspired by Robert Heinlein’s The Door into Summer, which is also full of self-learning robots, before they had digital data storage and microchips.

Carl Sagan got hooked on Mars long before university, thanks to Edgar Rice Burroughs's Barsoom series. Now, even the world of manufacturing is catching up with sci-fi through concepts like Design Fiction and Techno-fiction.

AI ON TIME: Dr. Mohamed Elsayed [right] teaching the machine teachers the art of thinking for themselves, first and foremost.

They don’t teach those topics here in Egypt, but in all fairness, I don’t think they’re known in China or India either. But all three countries seem to be making up for lost time through AI applications, whether classroom technologies, software solutions or university curricula.

So there’s hope on the horizon. I wish they had used some of those software solutions and AI applications for transportation. The bus conductor deliberately ‘misheard’ me when I said New Cairo and the Exhibition Land, dumping me at the old one in Nasr City and costing me a bundle.

Then there was the air conditioning in the exhibition halls that could give you pneumonia. That’s another waste of electricity, and I know from my own experiences in higher education that they have no more control over air vents than they do over hyperactive students!