Reviewed by Ameer Imam*

Some wounds never heal up and bleed for ages. History is always in a hurry. It never thinks what is left behind. It never cares if its work is finished or unfinished. It moves like a river without thinking for a while that its banks are taking new shapes. It whispers like the gust of air that does not care about the dust spiralling up to the sky. It dances to the tune of silence, but never lends an ear to the cacophony of emotions and longings. History is an outcome of hope and in the case of South Asia, it becomes the casualty of hope. In 1857, the failed Indian uprising was a shattered dream and its shards flew far and high that cut so many gashes open. The blood rushed and brought insecurities, misunderstandings, and mistrust out in open. The Independence was a fated revolution as its counter-revolution came precisely parallel. The partition was a counter-revolution. The streaks of blood drew a new country out of a land that was bound together by an ancient civilization. The political vivisection cuts it into two parts and the new part, like an amoeba, crawled to life at the exact moment of its birth. It runs at an alarming speed to another head to head collision with another mutilation; and in 1971, another surgery created another amoeba out of the previous one. The story does not end here though it seems to reach a halt for some time as after seventy years the separation is still hanging high in the air. The unfinished agenda of first Indian uprising marches on. It insists to remain unfinished. History keeps flowing to eternity without looking back. It does not stop; it can't. When a rocket goes up into the sky it drops down the unwanted parts down at the regular interval to intact its velocity. The same is true with History as it drops down blood, scars and dead bodies as unwanted to maintain its speed. That litter makes a fertile ground for literature, which to a good extent stands as an alternative to history. The good books come through a bad time.

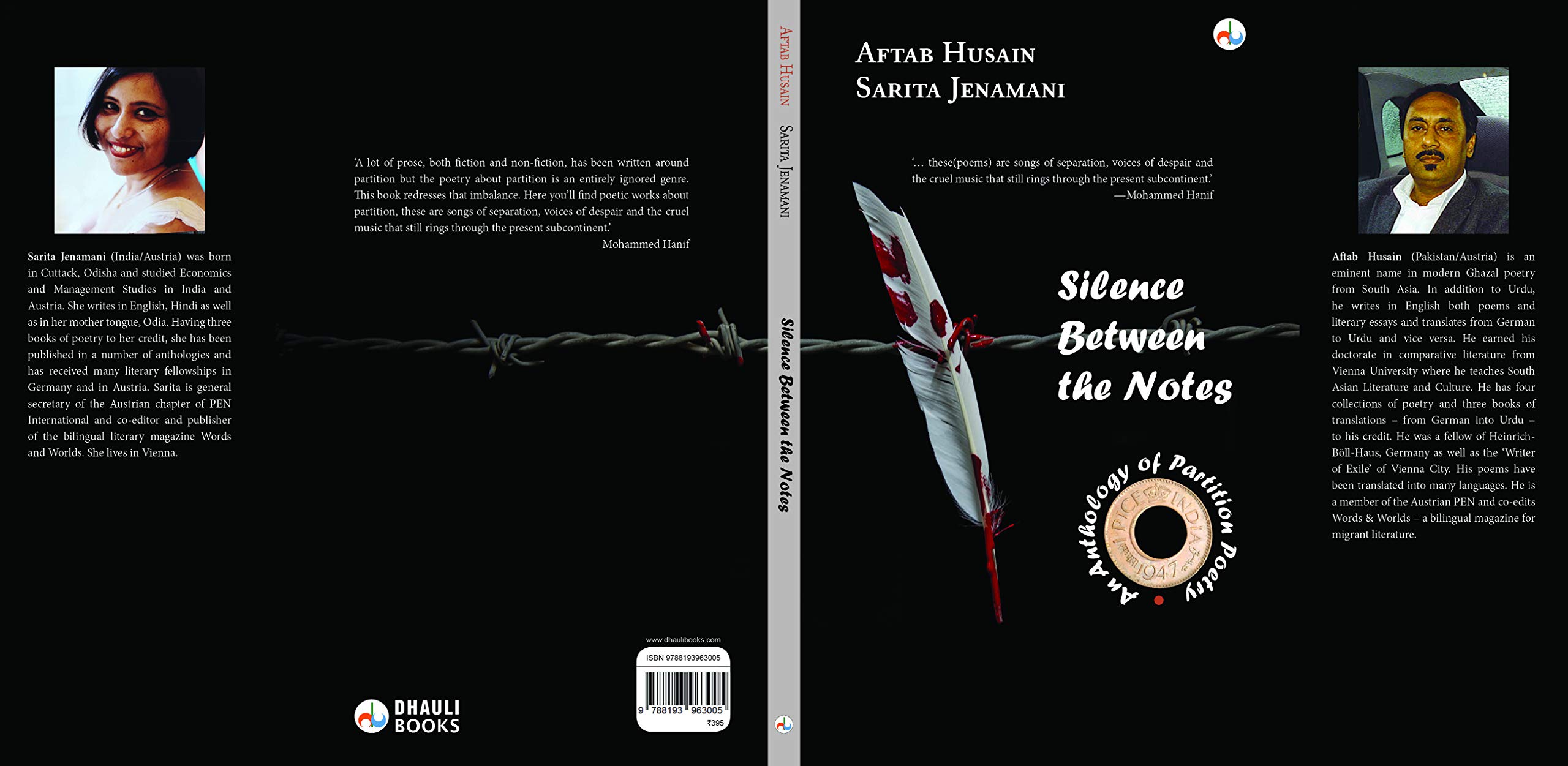

‘Silence Between the Notes’, an anthology compiled by Aftab Husain and Sarita Jenamani, is a collection of poems that deals with the trauma of the Partition of the Indian Subcontinent in 1947. It is a mosaic of human emotions, the abandoned pieces of history that until now could not be taken into account. Aftab Husain and Sarita Jenamani, the eminent literary personalities, coming originally from Pakistan and India respectively and based in Vienna, pick the poems so carefully that the reader finds before his eyes a canvas to observe the shades of sufferings as experienced by different people from different regions in this part of the world.

By picking poems from various south Asian languages the anthology deals with the trauma of Partition of the Indian Subcontinent in 1947 and offers a mosaic of the abandoned pieces of history; human emotions and sufferings experienced by different people from different regions in this part of the world - A subject that was so far not taken into account.

In the content list, we find works of literary stalwarts like Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Munir Niyazi, Sahir Ludhianvi, Ali Sardar Jafri, Akhtar Ul Iman, and Fahmida Riyaz and on the other hand, there are doyens like Agyeya, Kedarnath Singh and others. For many Zaki Kakorvi may become a new finding as he is not a well-known name in Urdu literature. Also, the poem of a very famous name in English literature; W. H. Auden, might be another discovery as it shows that even many English men were not convinced with the idea of the partition and especially the way it was pursued. One finds two poems by Taslima Nasreen as well, but a profoundly felt is the absence of Jaun Alia. I wish there were a single couplet, if not a complete poem penned by him, in this book.

Hasil e Kun hai yeh jahan e kharaab,

Yehi mumkin tha itni ujlat me.

(This mismanaged world is the result of the ‘Call of the Kun’ as it was the only possibility out of such a hurried process.)

The compilation as it has been carried by two seasoned poets and translators is up to the mark. A few translations are trans-creation. On the whole the book is a fruit of intense research work, but surprisingly enough we come to know that such a big tragedy has not elicited much response from our poets as Aftab Husain and Sarita Jenamani write in their introduction:

"our poets too resisted reacting immediately if they were not completely indifferent to the disquieting and sickening present. Many of them wrote poems about freedom but remained silent in dealing with the painful experience of the division of the country. Putting aside ‘Subh e Azadi’ by Urdu poet Faiz or, to some extent, Amrita Pritam’s ‘Aj AakhaN Waras Shah NooN’ in Punjabi, our collective memory can hardly recall a third poem on the subject"

They raise a valid question as why did the poets of that age not respond to the gruesome reality of their era. Were they not courageous enough or those cries simply did not hit a cord inside them? Were they of the view of German cultural critic T. W. Adorno, who said in the wake of the Second World War that writing poetry after Auschwitz would be barbaric?

The question is still unanswered. The book invites us to find an answer.

The poems of this book come from different poets from different regions and ages. It opens a window to understand how people from different regions would look at the division of the country.

It is a must read for those interested in the history and literature of this part of the world as seen through the eyes of its poets.

Dhauli books has done a commendable job by bringing out this much-needed and long-awaited collection of poems.

Best wishes for the book and many congratulations to Aftab Husain and Sarita Jenamani.

*Ameer Imam is a Central Sahitya Akademi Award Winner poet. He lives in UP, India.