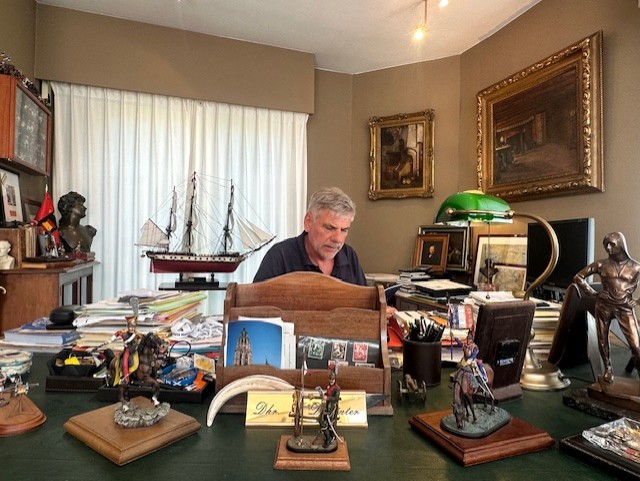

Faris Saleem Malouf (1892-1958) emigrated from Lebanon to the United States in 1907. Like many Lebanese immigrants, he started peddling, but Faris Faris S. Malouf, circa the mid to late 1930s, soon rose to prominence as a lawyer and politician in Boston, where he moved in 1909. He was very active and an incorporator in several Syrian organizations, such as the Syrian-American Club of Boston, the Syrian and Lebanese American Federation of the Eastern States, The National Association of Federations of Syrian and Lebanese American Clubs, the Institute of Arab American Affairs Inc., and the Arab National League of Boston.

By Charles Malouf Samaha

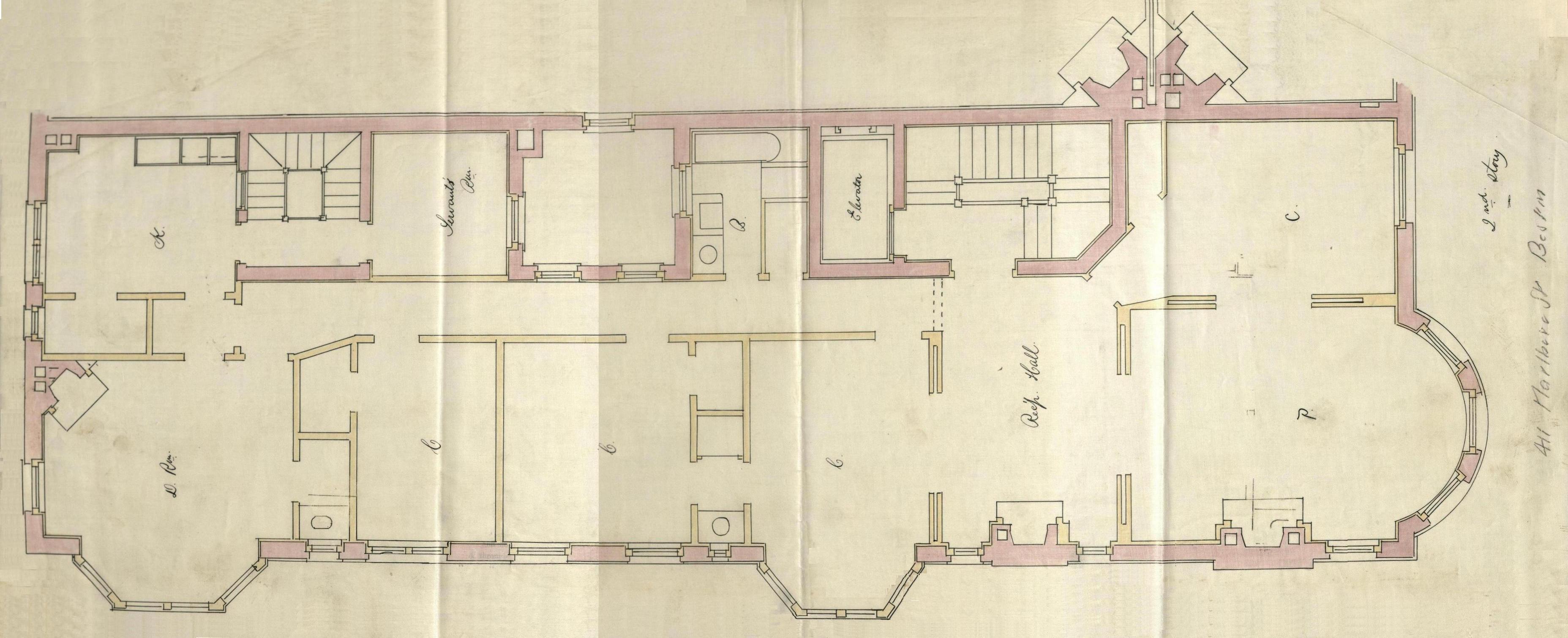

In the late 1910s, Faris met and became friends with Kahlil Gibran. During the land boom of the 1920s, Gibran and Faris decided to buy two seven-storied conjoined brownstones at 409 and 411 Marlborough Street (near Massachusetts Avenue), Boston. They were built in 1890 and changed ownership a dozen times between 1891 and 1922. The brownstone at 409 was designed as a twelve-unit apartment building, and 411 was designed as a six-unit apartment building. The two brownstones were a couple of blocks south of the Charles River and had about 160 rooms.

A fellow Syrian-American, Elias Shamon, who had graduated from Harvard Law School in 1923, represented Gibran and Faris at the closing in mid-February 1924. The men agreed with the seller, Grace McClary, on a price of $197,000. In conclusion, Gibran and Faris had a credit of $7,332.43 for unpaid mortgage payments, taxes due to the city of Boston, overdue water bills, and pro-rated rents. McClary was due adjustments for insurance and coal. Before closing, the men had paid a $2,000 deposit and a $4,000 commission. Also, all existing leases were transferred to Gibran and Faris. (A month later, McClary used the funds to purchase five brick houses in Newton.)

Gibran and Faris assumed responsibility for the two existing mortgages – a first mortgage to the Institution for Savings in Roxbury in the amount of $125,000 and a second mortgage to the South Boston Trust Company in the sum of $40,000 of which $35,200 remained unpaid. The second mortgage was payable quarterly in the amount of $1,500 principal with interest at 7% per annum. The men gave a third mortgage to McClary in the sum of $11,800 payable monthly in the principal amount of $200 plus 6% interest per annum. Therefore, at closing Gibran and Faris paid an additional $11,671.65 after all adjustments. The men equally split all payments.[1]

Around August 1924, they leased the buildings for ten years, effective October 1, 1924, to two single women, Josephine M. Quimby and Harriette M. Fowler. The two women intended to operate a for-women-only business, Fenway Business Women's Club, from the site. Gibran and Faris computed the necessary repairs and alterations to cost about ten to twelve thousand dollars. They were convinced that beginning in January 1925; the rent would be sufficient to pay for the upgrades and the existing three mortgages. The partners were happy at what they believed was a wise investment and hoped to raise money at a 6% interest rate per annum instead of 12-14% interest, which Faris balked about. (Gibran estimated their profit at about $12,000 annually,[2] which was a substantial amount, comparable to over $160,000 today.)

Second floor plan of 411 Marlborough bound with the final building inspection report 21Oct1891 v. 41 p. 52 courtesy of the Boston Public Library Arts Department

Second floor plan of 411 Marlborough bound with the final building inspection report 21Oct1891 v. 41 p. 52 courtesy of the Boston Public Library Arts Department

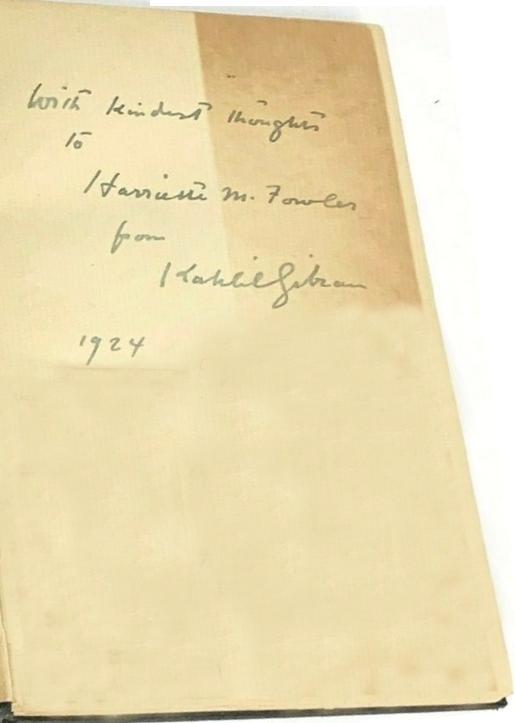

By October 1924, Gibran was despondent over the deal. He and Faris had committed over $12,000 for payment of the mortgages and renovations instead of toward their profit. Quimby and Fowler were unable to provide security for the lease and with three existing mortgages the men were unable to raise sufficient funds for the expenses and the workers on site, even at an exorbitant interest rate. Gibran confided in his friend, Barbara Young, that he momentarily considered filing a lawsuit against the women and that Fowler had audaciously asked him to sign her copy of The Prophet,[3] which he signed stating, “With kindest thoughts.” Gibran confessed to another longtime friend, Mary Haskell, he had been greedy or stupid as a small person “trying to do big things.” He then asked her if she knew of anyone who could help “two honest men going through financial difficulties.”[4]

By November 1924, Mary Haskell lent over $6,000 to Gibran, and the men received enough rental income to pay for some expenses. She also suggested that Gibran might use some of his paintings as collateral on a loan. Gibran was required to keep an account for her review. Their worries were temporarily relieved with Mary’s loan. Faris had also submitted a ledger of expenses to Mary.[5] Also, Faris raised money to cover his portion of the bills and debts from friends and family.[6] Gibran was optimistic throughout December:

“Malouf writes me that he is getting on very nicely for the present. He succeeded in getting help from his friends. He tells me also that the more he sees of Quimby and Fowler the more he believes in their integrity, as well as in their power to run the business successfully...

I know in my heart that all will be well in the future. The more I think of my plans the more sounder they seem. Faith is the source of all the worth while efforts of man. And I have faith. Sometimes I feel that even my mistakes are instruments carving in me a larger and a deeper place for a larger and deeper faith.”[7]

At the end of December 1924, Gibran wrote to Haskell: “I came to Boston on Christmas Eve and found that everything was getting on nicely. Quimby and Fowler are rather slow, but with a little patience on the part of everyone concerned all will be well in short time.”[8]

However, in early 1925, Quimby and Fowler defaulted on the rent. They told the men that to their regret they were unable to raise enough support for their proposed club to make it viable for them to lease the buildings. Also, the partners were unable to lease the buildings to others as they had been specifically outfitted for the club. The deal collapsed.

In March 1925, they were extricated from the morass when George Boardman purchased the property from them. The purchase was subject to the first mortgage held by the Institution for Savings in Roxbury and the second mortgage now held by the Federal National Bank of Boston in the unpaid amount of $28,000. Boardman also obtained the property subject to third and fourth mortgages in the unpaid amount of $10,825 and to the ten-year Quimby and Fowler lease. Gibran and Faris each netted about $3,000 from the sale. Shamon again represented them at the closing.[9]

Mary wrote Gibran in March 1925 and comforted him:

“But, Kahlil, dear, I’ve nothing to forgive…And only omniscience would never make a mistake… Your plan was just as likely to succeed as to fail. And that it failed, will matter for only a little while.”[10]

Gibran reflected upon this time in a letter to his friend and fellow writer, Mikhail Naimy:[11]

“God knows that never in my past life have I spent a month so full of difficulties, trials, misfortunes, and problems as the last month. More than once I wondered if my djinnee, or my follower or my double has turned into a demon who delights in opposing me, in making war on me, in shutting the doors in my face, and in placing obstacles in my way. Since my arrival in this crooked city I have been living in a hell of worldly problems. Had it not been for my sister, I would leave everything and go back to my hermitage, shaking the dust of the world off my feet.”[12]

It took a few years before both Gibran and Faris recovered from their financial loss.[13] On April 10, 1931, Gibran died. Three days later, on Monday, his body arrived in Boston from New York and was taken to the clubhouse of the Syrian Ladies’ Aid Society, where hundreds of mourners came and peered at the open casket. On Tuesday, representatives of the Syrian community escorted the body, encased in a casket draped with the Lebanese flag, from the clubhouse on West Newton Street, to the Church of Our Lady of the Cedars of Mount Lebanon, the oldest Syrian church in Boston, at 78 Tyler Street[14] where the Maronite Right Reverend Monsignor Stephen el-Douaihy (1882-1959) was rector and presided over the funeral service, which Faris attended in honor of his old friend and partner. The church was at capacity and many waited outside on the sidewalk. Najeeba Murad, whom both Gibran and Faris admired, sang during the service.[15]

Gibran’s memorial service in Boston was held on Sunday, May 24, 1931, at eight p.m., at the John J. Williams Municipal Building at the corner of Shawmut Avenue and West Brookline Street. Over a thousand Syrians, including Faris, attended. Speakers included el-Douaihy, Wadie Shakir, Labeebee Hanna, and Shamon.[16] A final tribute to a successful Bostonian Syrian.

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Francesco Medici with this article.

* Most of the foregoing was excerpted from Faris Saleem Malouf (1892-1958) - A Voice In The Dark: One Man’s Arab American Activism, by Charles Malouf Samaha.

The author may be contacted at [email protected]

Credits:

Carlos Slim Foundation

Museo Soumaya

Bibliography

Gibran, Jean and Kahlil George, Kahlil Gibran: Beyond Borders (Northampton: Interlink, 2017).

Gibran, Jean and Kahlil George, Kahlil Gibran: His Life and World (New York: Interlink, 1991).

Naimy, Mikhail, Kahlil Gibran. A Biography (New York: Philosophical Library, 1950).

Otto, Annie Salem, The Letters of Kahlil Gibran and Mary Haskell; Visions of Life as Expressed by the Author of “The Prophet” (Houston: A. S. Otto, 1970).

Young, Barbara, This Man from Lebanon (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1945).

[1] Commonwealth of Massachusetts Land Records; Closing Statement, Kahlil G. Gibran Collection; M. Naimy, Kahlil Gibran, p. 196; J. & K. Gibran, Kahlil Gibran: His Life and World, p. 375; J. & K. Gibran, Kahlil Gibran: Beyond Borders, pp. 369-376.

[2] Letter from Gibran to Mary Haskell, September 4, 1924. Minis Papers, Collection #2725, Folder 275.

[3]B. Young, This Man From Lebanon, p. 13.

[4] Letters from Gibran to Mary Haskell, October 3, November 12, and December 4, 1924. Minis Papers, Collection #2725, Folder 275.

[5] Letter from Gibran to Mary Haskell, November 12, 1924. Minis Papers, Collection #2725, Folder 275.

[6] Letter from Gibran to Mary Haskell, October 3, 1924. Minis Papers, Collection #2725, Folder 275. J. & K. Gibran, Kahlil Gibran, p. 376.

[7]A. Salem Otto, Letters of Gibran and Haskell, p. 659.

[8]A. Salem Otto, Letters of Gibran and Haskell, p. 659.

[9] Commonwealth of Massachusetts Land Records and Otto, Letters of Gibran and Haskell, p. 662.

[10]A. Salem Otto, Letters of Gibran and Haskell, p. 661.

[11] Born in Baskinta, Lebanon; 1889-1988.

[12]M. Naimy, Kahlil Gibran, p. 197.

[13]M. Naimy, Kahlil Gibran, pp. 197-198 and J. & K. Gibran, Kahlil Gibran: Beyond Borders, pp. 375-376.

[14] Its chapel, which was originally at 66 Tyler Street, was dedicated on January 8, 1899. The first priests were Gabriel Corkemaz, Joseph Yazbek and his nephew Joseph K. Yazbek, and Stephen Corkemaz.

[15]“Gibran a Year After.” (1932, April). The Syrian World, pp. 27-8; “Body of Khalil Gibran Arrives in this City.” (1931, April 14). The Boston Daily Globe, p. 4; Young, Barbara. (1931, April). “Gibran’s Funeral in Boston.”The Syrian World, pp. 23-25.

[16]“Hold Memorial Service in Honor of Mystic Poet.” (1931, May 25). The Boston Daily Globe;“Gibran Memorial Held in Boston.”(1931, May). The Syrian World, pp. 51-2.

Copyright © 2020 by Charles Malouf Samaha. All rights reserved.

Reprinted by permission of the author.