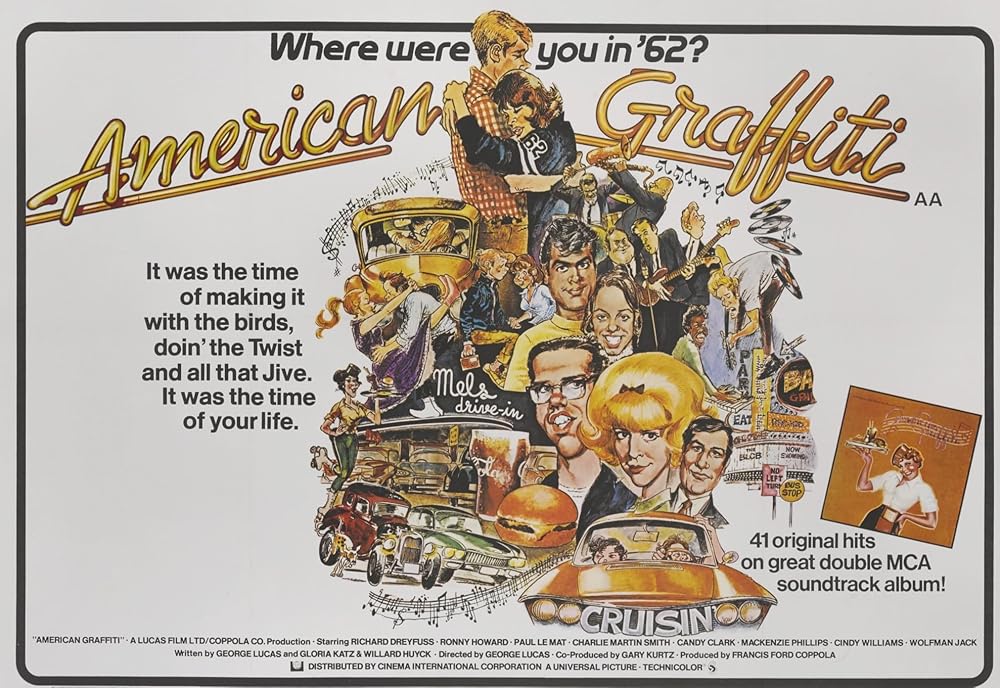

With some reservations, I watched one of George Lucas’s non-sci-fi epics, American Graffiti (1973), a forgotten coming-of-age comedy-drama film. I have to admit; I was completely blown away!

By Emad Aysha

This movie is a classic, possibly the best 1950s flick ever made, immortalising that long lost world of smalltown America with its suburban frolics and claustrophobic sprawl. (Side-by-side with another classic like David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, although substituting docudrama pop realism for warped surrealist film noir.)

I’ve never seen a movie that’s so informative before; and I like Blue Velvet. It summarises everything about that slice of Americana you never saw because you weren’t around back then or come from somewhere else. It’s more authentic than movies actually made in that era.

There were custom-built hotrods, overcrowded roads, neon lighting and flared colours, adult supervision at dances, fast-food culture, listless hyperactive teenagers out on the prowl just looking for trouble, and their own slang, which is still used to this day. Added to all the hubbub to liven things up was the endless stream of big band hits at the time and the radio commentary to go with it.

CAPTIVE TALENTS: George Lucas, one of a long list of prisoners of the Hollywood moneymaking machine.

Music back then was so different. People had one thing to talk about and one thing only: love and beauty. Once you find the right girl, music fills you with hope and makes you want to do the right thing. The young people here make lots of mistakes, but you can tell at heart they’re pure and very responsible.

You were heartbroken on what happened to John Milner (Paul Le Mat) in the epilogue. He’s the most responsible guy here, a man of limited prospects in life who is a stand-up guy and doesn’t let his hotrod fame go to his head. You really thought he’d met the right girl with Carol (Mackenzie Phillips) and was going to settle down.

The dominating problem for the kids, apart from isolation from the wider world, is boredom. There’s just not that much to do to the point that anything is a desired distraction – even watching an axe murderer dismembering somebody.

Not to mention screwing with the cops and joining a gang, which is what happens to Curt Henderson (Richard Dreyfuss) here, of all people. There’s a constant sense of nastiness lurking somewhere round the corner, with guns and crime and an obsession with booze and money. There’s a sense of dilapidation also lurking behind the scenes.

You know it can’t last. Hence, the scene with the Wolfman, where he confesses to Curt that the icebox is out and all the popsicles in it are melting. That brief period of respite that was the 1950s, with stable homes, stable jobs, and a bulging middle class, simply couldn’t last.

Only somebody like Lucas could have pulled it off. I never thought I’d say this, but it’s a shame he went into science fiction and special effects. He’s a talented storyteller and a tremendous down-to-earth world-builder.

American Graffiti isn’t as epic as Star Wars, and there’s no one quite like Luke Skywalker or Han Solo, let alone the droids. However, despite its lack of plot, it’s such a well-rounded movie and expansive world. The characters, their passions, and weaknesses carry you along, with the music and sights igniting your sensibilities.

The dialogue, in particular, was snappy, and it was nothing at all like what you get in the Star Wars prequels. It’s full of meaning and hurt in some cases, but very grounded, natural, and funny, especially the tit-for-tat scenes between Bob Falfa (Harrison Ford) and Milner, not to mention Ron Howard and Cindy Williams.

The movie is a documentary without many close-ups and lots of cataloguing of fun facts, but the endearing quality of the characters, along with subplots and subtle themes, foregrounds it enough for you to see it as a movie.

The movie even answered some anthropological questions I’d always wondered about, such as the American penchant for having sex in the backseat of a car. It seems cramped and demeaning, but girls get a kick out of it because the vehicle attracts them to a guy.

Hence the storyline between Terry Fields (Charles Martin Smith), a clear stand in for Lucas, and the strumpet Debbie (Candy Clark). No wonder Americans like Oreo biscuits so much. They like the taste of fame or fashion, not substantive things like authentic food.

CINEMA SPLICE: Obi-Wan (Ewan McGregor) taking a trip down somebody else's memory lane in 'Attack of the Clones' (2002).

There’s a fast food joint on roller skates here, and it’s referenced in Attack of the Clones, a scene I actually liked, would you believe it? It’s those little details and jibes that make all the difference, making it a lived-in reality that’s colourful, nuanced, and enjoyable.

If it hadn’t been for American Graffiti, there would have been no Star Wars, literally in the case of Han Solo because he was based on Milner’s rival in the movie. (Harrison Ford being in Star Wars was a coincidence though, since Lucas wanted Christopher Walken).

A lesson for all those other would-be world-builders out there. (Yes, I’m talking about you-know-who from the new Dune movie). Not only did Hollywood force George Lucas out of mainstream cinema, it sucked in people who wouldn’t know world-building if it hit on them on the head.

Ironically, Christopher Walken ends up being the emperor in Dune, part two. If only he’d signed on to Star Wars, he would have learned to be something other than himself – someone who always talks like a failed blue collar gangster.

Blame Hollywood for typecasting him too, not to mention killing off Han Solo in the most demeaning way possible in the Star Wars sequels. One of my favourite lines in Graffiti is when Milner says: “Rock and roll's been going downhill ever since Buddy Holly died.”

The same holds true for world-building in Hollywood, to boot, not to mention casting and directing and everything else.