What does the combination of science and science fiction have in common? From that perspective, Dr Tarek El-Shennawy is a rarity in Arabic sci-fi. He’s an actual scientist and does a fair amount of research on the discipline of SF itself.

By Emad Aysha

Dr El-Shennawy can look back on a fascinating career. He was born in 1972 in Alexandria, has a doctorate in electrical engineering, and is currently working in energy conservation in the petroleum sector. He was schooled in books through his father’s extensive library, including Hilmi Murad’s book series summarising the great works of world literature.

SF came through translations of Wells and Verne, the pocketbook series of Nabil Farouk and Ahmed Khaled Tawfik, and then Nihad Sharif (born in the same district of Alexandria as Dr. Shennawy). At university, he also got to know the works of Einstein, Schrodinger, Sagan and Asimov and began to realize the scientific gulf separating us in the Arab world from the West, with Noble Prize winner Naguib Mahfouz himself not taking SF seriously.

INTELLECT AT LARGE: Dr. Tarek Ibrahim El-Shennawy proves that science fiction, like science, is a group enterprise.

What about the sci-fi scene in Alexandria?

“In 1995, my last year at university, I joined the arts and authors group Atilya Alexandria (أتيليه الإسكندرية), headed by the now deceased Dr Muhammad Rafik Khalil, a man with an encyclopedic knowledge as a medical doctor and poet and historian of music, among other things. There, I also got to know Edward Al-Kharat, Ibrahim Abd al-Majid, Mustafa Nasr, Ahmed Fadl Shablul and someone dedicated to simplifying the sciences through SF like Ragab Saad al-Sayyed.

With friends like Ahmed Fawzi, Hatem Ali, Iman Abd al-Hamid, Islam Badr, and Jihan Abd al-Aziz, we set up a short story workshop, emphasizing science fiction. We were all in our twenties, but sadly, our work lives caused us to go our separate ways. We’ve had to resort to online forums for science fiction instead.”

I was very intrigued by your story “The New Gods of Man” (آلهة الإنسان الجديد). In it, a Russian scientist makes a correlation between global warming, power struggles between the US and Russia, and viral epidemics.

“That story won a prize in a sci-fi contest, and the resulting book went to the Cairo International Book Fair 2024. Conspiracy theory actively controls many themes in science fiction, although our current reality is much worse.

The Russian scientist escaped to the US and convinced a billionaire to build a colony on Mars or the moon. The businessman consequently saw himself as a god for this new human community, having given these people a new lease on life.”

Then, there was the story of a robotic football match in the future between Tesla and Honda, with cyborgs replaced by robots.

“The idea for that story came to me while I watched documentaries about robot evolution towards humanoid robots. It came at a time while I was following the story of a football player who was poorly injured in a way that could have threatened his career.

That’s when it occurred to me: would the rules allow a cyborg to play – a human augmented with machine parts? And then could it be that such cyborgs, who do enjoy human rights under the law, replace us as normal human beings? And then, could humanoid robots replace those cyborgs, and is this a good thing?

Come to think of it, could we get robots that replace sporting legends, especially given how expensive players have become now? I was able to publish this story in Sweden with some help from the World Union for Arab Intellectuals (الاتحاد العالمي للمثقفين العرب).

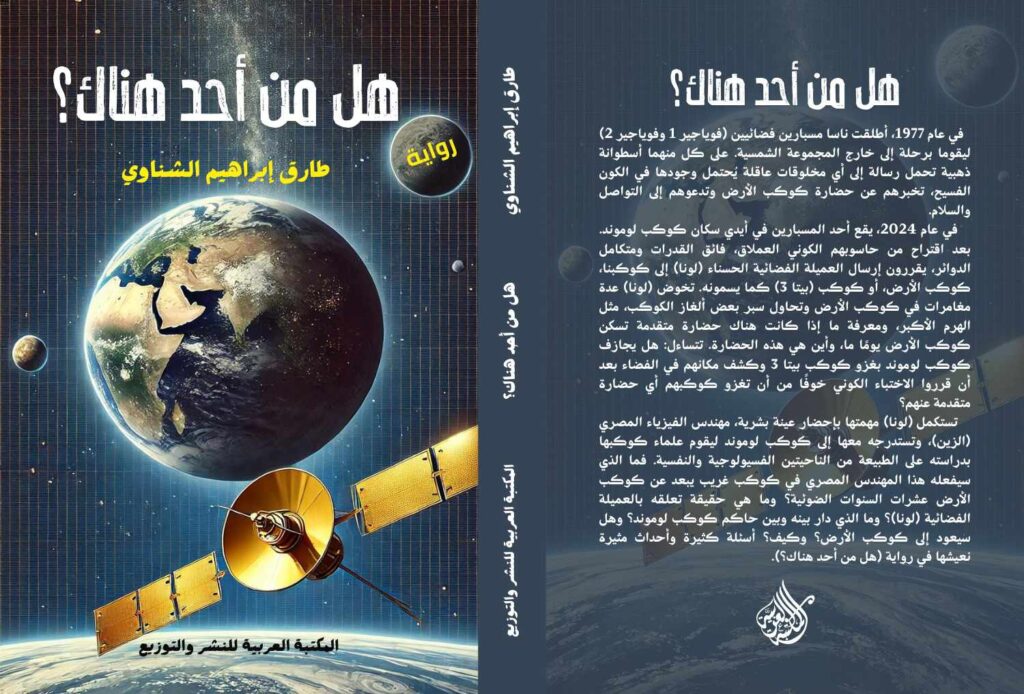

Another page-turner is You Is Anybody There (هل من أحد هناك).

“The story is based on an actual event: NASA launched Voyagers 1 and 2 in 1977, with the golden disc carrying a message to any intelligent life. That’s where the fiction comes in, with Voyager falling into the hands of the residents of the planet Lumund. They fear that this primitive device was built by a more advanced race, hoping to trick them into exposing themselves and being open to attack.

Lumund itself is an imperial power, exploiting several planets it occupies. Does their supercomputer suggest they sent a secret operative to our miserable little planet to soy on us as well as solve riddles, like the secrets of the pyramids – built by a dead human civilisation or aliens? She then brings back a human ‘sample’ with her, an Egyptian physicist and engineer, so that he can be studied physiologically and psychologically. That’s when the action gets going. I won’t spoil it for you!”

FORGOTTEN POSSIBILITIES: Imperialism may exist in outer space just as it exists here. Should be careful who you invite to the party in the meantime.

As a scientist, do you believe science fiction can promote the education of science at schools and universities in Egypt?

“I’ve taught at several universities and academies over the past 30 years, but even many scientists belittle science fiction and literature. Teaching the sciences demands a total overhaul in the way we teach, the mindset of the teacher himself, and the environment we live in.

We must abolish rote learning and memorising by heart once and for all. We must have wide-ranging discussions about science at school and university. We must allow questions that seem naïve or even stupid.

Especially the questions about the philosophy of science and why things happen the way they do. We need the imagination, in short, because without the imagination, there can be no renewal and progress. Just look at the classics; everything predicted by SF writers from 100 years ago has come true. But the environment is so restrictive and discourages asking questions. When a teacher is asked something he doesn’t know, he will scold his pupils to save face.

Science fiction is essential for the whole educational complex, not just for students but for teachers. I hope that science fiction is used at school, in particular, to help raise questions among the young. Without this, we can’t progress, will remain consumers of Western technology, and will eventually fall light-years behind them.”