For more than three decades, Western Europe has wrestled with one of its most sensitive subjects: criticism of Islam. While the scrutiny of Christianity and Judaism has become routine, and political ideologies are freely contested, Islam remains encircled by a unique set of taboos. Islam critics risk violent retaliation and are set aside as xenophobic.

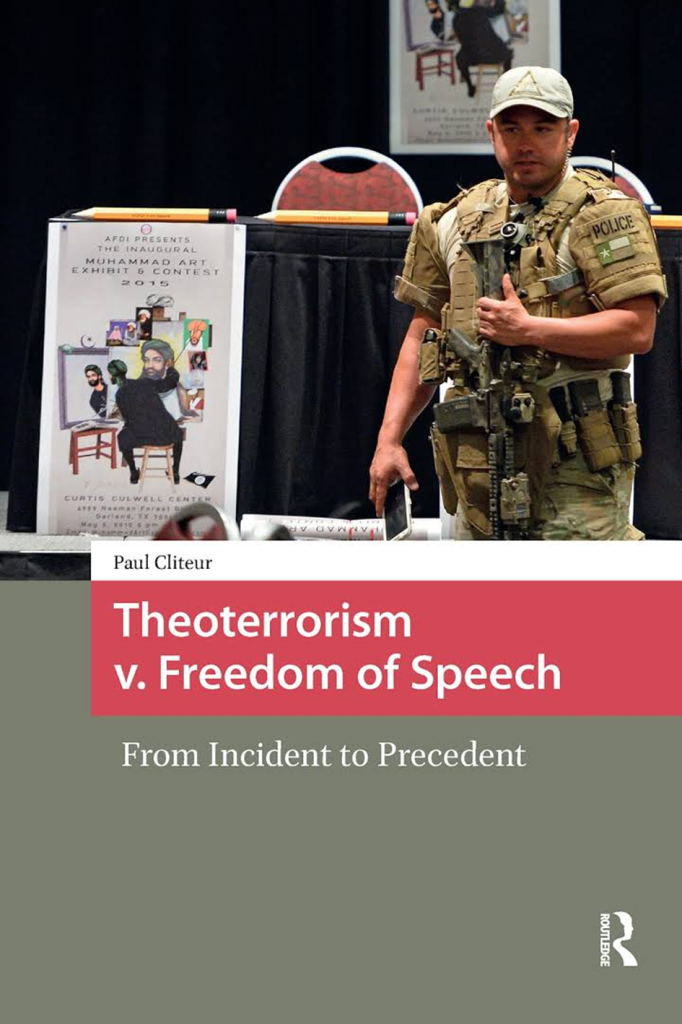

By Paul Cliteur

The first risk of violent retaliation is underscored by attacks on figures such as Salman Rushdie, Theo van Gogh, and the editors of Charlie Hebdo. At the same time, the social stigma attached to voicing such Islamic criticism is routinely dismissed by the (radical) left as xenophobic and even racist.

The Netherlands stands out in this landscape. Unlike most European countries, it has seen several high-profile political figures attempt to articulate a liberal critique of Islam. Their experiences — from Frits Bolkestein in the early 1990s to Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Geert Wilders and, more recently, Keyvan Shahbazi — reveal both the possibility and the fragility of such efforts.

A Pioneer Without Successors

The starting point is 1991, when the late Liberal Party (VVD) leader Frits Bolkestein argued that European civilisation was grounded in rationalism, humanism and Christianity, and that its core values — the separation of church and state, freedom of expression, tolerance and non-discrimination — could not be compromised. He warned that the cultural assumptions of liberal democracy were difficult to reconcile with religious and political traditions in much of the Islamic world.

His intervention triggered fierce political backlash. Critics accused him of cultural arrogance and inflammatory rhetoric. Rather than opening a sustained debate, the episode effectively closed one. Within the VVD, Bolkestein’s concerns found no lasting echo; his attempt to place Islamic criticism within a liberal framework stalled almost immediately.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali and the Post-9/11 Reckoning

The attacks of 11 September 2001 reconfigured the debate. Ayaan Hirsi Ali — a Somali refugee who had survived forced marriage and female genital mutilation — emerged as a compelling new voice. Fluent in Dutch and trained as a political scientist, she questioned the compatibility of certain Islamic norms with liberal democracy. Her 2001 article “Give Us a Voltaire” challenged Western intellectuals for celebrating religious critique in principle but avoiding it where Islam was concerned.

As a VVD MP, Hirsi Ali brought a perspective shaped by personal experience. Her collaboration with filmmaker Theo van Gogh on the short film Submission provoked international controversy. When Van Gogh was assassinated by an Islamist militant in 2004, the episode marked a turning point: the threat of violence against Dutch critics was no longer hypothetical.

Despite her prominence, Hirsi Ali’s position within Dutch politics was precarious. She received limited support from her own party and faced sustained security threats. In 2006, she left the Netherlands for the United States. Her departure signalled both the seriousness of the risks and the difficulty of maintaining such criticism within a mainstream political context.

Geert Wilders and the Politics of Isolation

After breaking with the VVD in 2004, Geert Wilders founded the Party for Freedom (PVV). Unlike Bolkestein or Hirsi Ali, Wilders placed Islam — not merely radical Islam — at the centre of his political project. This position has earned him serious security risks and a high degree of political isolation.

Wilders operates under constant protection and has been the target of multiple plots by Islamist militants. At the same time, his critics portray his approach as discriminatory and inflammatory, effectively excluding him from mainstream political alliances.

This combination — the physical threat on the one hand, and the moral stigma on the other — has shaped the broader climate. Many politicians, academics, and commentators avoid the subject, yet their silence is often framed not as fear, but as nuance or respect. The result is a debate marked by avoidance rather than engagement, and by rhetoric that obscures rather than illuminates the underlying tensions.

A New Voice With Familiar Arguments

In recent years, the Iranian-born psychologist and writer Keyvan Shahbazi has put forward a new critique in his book The Price of Freedom (2025). Drawing on his experience of the Iranian Revolution and the rise of Ayatollah Khomeini, he argues that contemporary Islamist violence cannot be separated from core doctrines of the faith. Shahbazi focuses less on extremism than on what he calls “pure Islam,” which he regards as inherently incompatible with liberal democracy.

While his analysis is couched in autobiographical narrative and moral urgency, it closely resembles the arguments Wilders makes. Yet Shahbazi publicly distances himself from the PVV, describing it as “aimless populism.” In my view, this distancing reflects the incentives of the Dutch mainstream: to maintain influence within policymaking circles, one must avoid any association with Wilders, regardless of substantive overlap.

This dynamic highlights a paradox. The most uncompromising critique today comes from figures who cannot afford to embrace one another publicly. The effect is fragmentation rather than consolidation, leaving Islamic criticism politically directionless despite the persistence of underlying concerns.

The Structure of a Taboo

What unites the experiences of Bolkestein, Hirsi Ali, Wilders, and Shahbazi is the pattern of initiation, backlash, and retreat. Political peers rebuked Bolkestein; Hirsi Ali was driven abroad by threats; Wilders continues under extraordinary protection; Shahbazi risks marginalisation should he acknowledge the full implications of his own arguments.

Meanwhile, the issues these figures raise show no sign of disappearing. Debates over religious symbols in public institutions, the boundaries of free expression and the role of religious doctrine in liberal societies remain urgent. They intersect not only with immigration and integration, but with constitutional questions surrounding the rule of law.

Yet the political space for addressing these issues has narrowed. The threat of violence discourages candid debate, while accusations of racism or xenophobia suppress dissent from within mainstream institutions. The combination makes Islamic criticism in liberal politics not simply controversial but, in many cases, untenable.

A Democratic Imperative

The Dutch experience offers a broader lesson for European democracies. Whether one agrees with these critics or not, a political culture that cannot accommodate a searching examination of any religion risks undermining its own liberal foundations. The values Bolkestein invoked — free expression, tolerance, non-discrimination, secular governance — depend on the ability to question powerful beliefs, including religious ones.

If such scrutiny becomes impossible, the realm of public debate contracts. And when self-censorship takes root, shaped by fear or stigma, democratic decision-making becomes increasingly fragile. For now, the Netherlands continues to grapple with these tensions — a country where the arguments for a liberal critique of Islam remain as relevant as ever, yet where those who make them often stand alone.