The Levant News Exclusive – By Emad El-Din Aysha, PhD

Dear Mrs Zoha Kazemi,

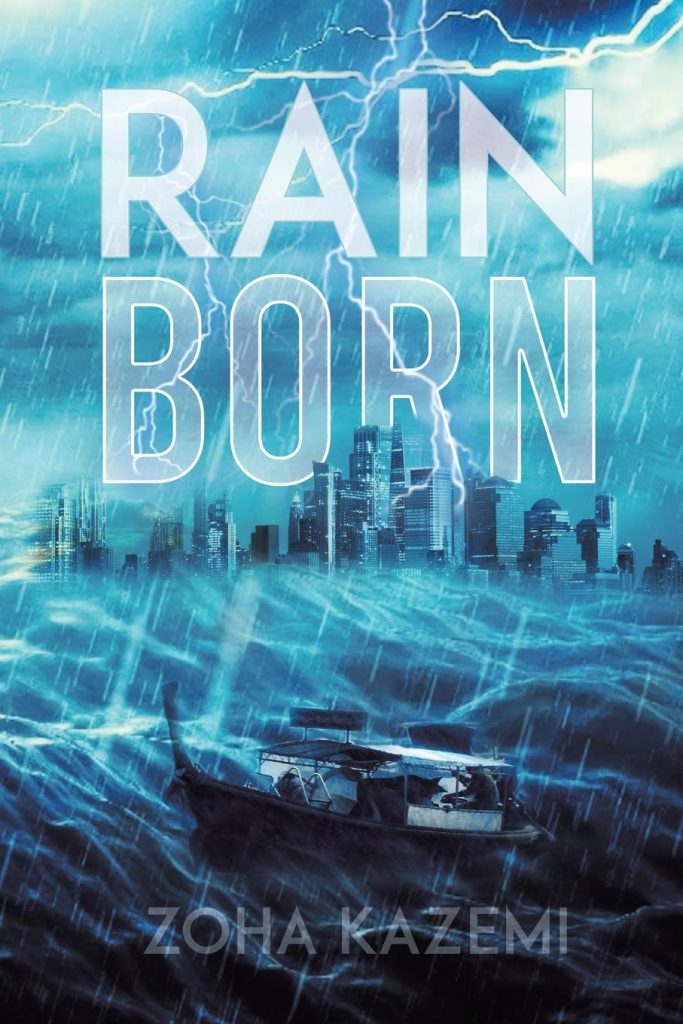

Please let me express my gratitude for this opportunity. It’s not every day that you speak to Iran’s most widely published sci-fi novelist, and one who has been published in English no less. (Best of luck for your two novels Rain Born and Year of the Tree: A Novel). And thank you for providing me with samples of your short fiction (“Isolation” and “Superstar” from your anthology Time Riders) and details of your novels and career.

Thank you Mr. Aysha for this great opportunity. It is an honor talking to a sci-fi writer from Egypt.

First off, please give us your ABCs. Your education and upbringing? Where you were born and who your favourite authors are (from Iran and abroad)? What drew you to writing and to science fiction specifically?

I have a BS in Material Engineering and an MA in English literature, both from Iranian universities. I lived in London in my teenage years but moved back to Tehran when I was 17, and I’m currently living in Tehran with my husband, my daughter and two cats! Since I lived a few years in the UK, I had the opportunity to learn English and become familiar with English literature. I started reading Arthur C. Clark and Isaac Asimov back then, who are two of my most favorite authors. I also love the stories of Philip K Dick whom I believe has had the most influence on my writing. But my favorite author is Jorge Louis Borges! I do love Iranian poetry and the stories of Sadegh Hedayat. My favorite contemporary Iranian author has to be Behzad Ghadimy with his horror and dark fantasy stories.

I was always a sci-fi fan from an early childhood. Nothing could overcome the pleasure of watching Star Wars for me! But in Iran’s fiction, we never had an outstanding sci-fi novel and I didn’t know who to look up to or how to write Iranian sci-fi. It took a great courage and a leap of faith for me to change my fiction genre to sci-fi and start writing speculative fiction. I had published four books (three novels and a flash fiction collection) before I realized I wanted to write sci-fi. Everyone thought it was a high risk since it was a vague path. No one knew whether publishers would accept my book and if there were any readers for it. I published “Pine Dead” around six years ago. It’s a story about a virus pandemic that kills many people all around the world, a bit like what we later on experienced with Covid-19. The book was well received and I got the courage to continue writing in science fiction.

What other genres do you write in? And how does writing science fiction differ from fantasy or realistic fiction or period drama?

I started my writing career with realistic fiction, tackling social and feminist themes and cultural and religious trauma in my first five books, Beginning of the Cold Season, Sin Shin, Year of the Tree, Has Someone died Here? and my flash fictions. Year of the Tree and has a magic realism touch to it and Has Someone Died Here? is more surreal than realistic fiction. The first main difference between a realistic fiction and speculative fiction is the worldbuilding. In my dystopias I create new and self-sufficient worlds and in the defamiliarized setting, I write about more fundamental and global themes like love, death, hope, etc. If you want to write about these ideas and themes in a realistic setting, they may side with clichés more often than expected. I try to combine my worldbuilding with Iranian settings. For example, The Juliet Syndrome takes place in a future Tehran and it’s about a dystopian society where people can’t fall in love anymore and they have to “buy love” from big companies that are ruling them.

Where do you get the inspiration for your stories? Please give an example.

Inspirations are everywhere! There are so many complexities and problems all around me that I get inspirations from. Living in the Middle East, with the never-ending struggle between modernism and tradition and the weight of its historical background combined with religious ideologies, provide so many ideas to write about. I find most of my themes in my everyday life in Iran. The hard part is translating these themes and reflecting them into an exciting speculative story.

For example while Rain Born takes place in a post-apocalyptic future it is similar to the turbulent political atmosphere of today’s Middle East where war is always at the door. I wanted to explore the extent that religious beliefs and myths penetrate the everyday life of people and how political and economic decisions based on them, enslave men and women, sometimes making them suffer. One of my main reasons for writing Rain Born was to challenge the concept of faith and nature and their relevance to humankind. I have seen many religious people change as they get older. As time passes and they gain a more realistic view of life and human nature, they usually become softer in their views. But it all depends on how deep their beliefs were rooted and how hard they were challenged in their lives. Sometimes as in the case of my main character Tirad, the beliefs are very strongly rooted and the life challenges are great. He has to make difficult choices, weighing his socially constructed beliefs and what he feels to be right in his heart as a human being.

I’ll have you know you’ve been officially classed a cyberpunk author. I incorporated you along with some of your fellow Iranian authors – Mehdi Bonvari and Muhammad Faezifard – during a presentation I made as a moderator at Chicago Con 8 with my two esteemed colleagues Dr. Valentin Ivanov (Staff Astronomer, European Southern Observatory, from Bulgaria) and Hirotaka OSAWA (AI expert from Japan) – “Cyberpunk Traditions Outside the United States” (1 September 2022). One of the works cited by Dr. Valentin was the novel Our Markov’s Processes by the late Ivan Popov, where the mafia takes over a maths faculty at a university because they are the only people who understand the value and profitability of knowledge.

That reminded me of your story “Superstar” where the young struggling writer is used as a prop for the villain who became a celebrity author by stealing other people’s dreams (ideas for stories) quite literally robbing them from their subconscious minds, electronically.

Is copyright fraud a problem in Iran? It certainly is in the Arab world. I have a friend who was planning to be an SF author who gave up because he found somebody else getting prizes for his ideas!

Iran has not joined the international copyright acts. But we do have internal copyright, although it is very hard to prove if someone has stolen our idea. At the end, the problem your friend had doesn’t apply either. Since there are no prizes or commercial advantages, no one bothers to steal someone else’s ideas.

Copyright comes to light when Iran publishers translate and publish foreign works without permission or payment. This puts us as Iranian authors in a bad situation. We have to compete with the best books in the world that are cheaply published here and sell well. On the other hand, foreign publishers tend to step back when it comes to buying the copyright of an Iranian book since they believe we are only there to sell our books while we publish their books in Iran without paying and permission.

As for my story “Superstar”, first I have to say this story is my readers’ favorite. I didn’t expect readers to like this story so much but I have been getting very good responses from them since it was published. “Superstar” tackles the problem of fake celebrities and the Literary mafia in Iran that doesn’t allow novice writers to get published. The literary circle in Iran is closed and it is very hard to get into. They tend to discourage many new writers and have the works of their friends and affiliates get published and promoted. Fortunately, this doesn’t apply to speculative fiction.

What is your relationship to computers, in fact? Do you write everything on a PC/laptop or do you use pen and paper or an old-fashioned typewriter?

I’m also an engineer and although I’m skeptic of AIs, I’m good with computers and other electronic devices.

I write my stories on my laptop. Since I type fast, it’s easier and more efficient for me to type rather than to write on paper.

Let me commend you now for your story “Isolation”, about a future world where people live in cells and interact via VR because of a genetic allergy. It’s not just that you envision such a harrowing and detailed future world but you immerse us in the world so nicely and pull us along with the unfolding plotline so effectively. I’ve always suspected Iranians are great storytellers from watching Asghar Farhadi movies. Likewise there is a lovely beat to your story. You can literally feel the city beneath your feet, as if you had to walk everywhere in the pre-internet world, and that’s despite all the technology on display. I actually found it easier to picture the scene at the Tehran café than the laboratory. It was more lively and colourful and ‘real’.

Is this generational on your part, that you grew up before computers became ubiquitous? Not to mention mobile phones, email and even fax machines. I grew up in that pre-high tech world myself!

I was born in 1982 and I remember the pre-high-tech world, not to mention that Iran was a decade behind western countries in digital technology. I do have a nostalgia towards those times and would like to bring such nostalgia into futuristic settings to create further defamiliarization. Even in real life, I do like spending some time away from my computer and specially from social media and take shelter in what I believe is a beautiful reality that we seem to be losing our touch with. I still prefer paper books to electronic or audio books which I think is rooted in my childhood. Also, in my story Isolation I wanted the setting to have some sort of Iranian taste to it, not a far ancient or Islamic taste, but a more recent one. That’s why I chose a café which is similar to the cafes we go to in Tehran.

Isolation is also a very romantic story. The ending is tragic, with the lady scientist Sayeh dying from the genetic allergy she herself cured, but her boyfriend Kamran living on nonetheless. What do the names of the heroine and hero mean in Persian? Also, would you say that romance – stories of true love and sacrifice – are a bit lacking in SF, or is SF in Iran different than in the West?

Sayeh is an Iranian name that means shadow. In the Persian version I play with Sayeh’s name in a literal way. I chose this name because I felt that if man becomes deprived of human touch and connection, he loses his reality and perhaps only a shadow seems to remain.

Kamran is also a popular Iranian name meaning lucky. In the story we see at the end that he was lucky indeed!

I believe that a story without romance is like food without spice and you know how much middle-eastern people love spices! In my opinion, characters should be life-like and believable even in sci-fi stories. Real people experience love and human emotion in one way or another and this important aspect that makes us human should not be ignored when writing speculative fiction. Love is a strong emotion and shapes the way we are. One of the things that make characters special and exciting is the complex emotional relationships they have. The way a character reacts to love and the complexities surrounding it, makes for a good story.

That’s very interesting. There’s a famous Egyptian novel, a classic, called The Man Who Lost His Shadow. Also a friend of mine – Mahmoud Abdel Rahim – did a cyberpunk story where people have to live in isolation of each other, relying on advanced virtual technologies that allow you to ‘feel’ and ‘kiss’ and design your own clothes, because of nuclear war and plague. (People isolated in cities with an invisible barrier that keeps out the radiation, and then live and work at home because of plague). The hero is planning to get married but he’s never actually met his future bride, in person, and so can’t even be sure she exists. When he kisses his mother’s hand, he runs out of credits and his virtual link is cut. Even if he marries and has children the state takes your kids away at age 10 for isolation. He decides to brave the wilderness outside the city barrier and he finds his bride by his side at the last minute. They hold hands and go out together!

Seems great minds, and similar cultures, think alike. On that note, are you drawn to tragedy in your stories or do you prefer happy endings?

Unfortunately, I haven’t read Mr. Mahmoud Abdel Rahim’s novel but the idea is certainly similar to my story! It’s very interesting when two people who don’t know each other right about similar subjects and themes. And I agree with you that this calls for a closer critical and comparative analysis. It will be interesting to know why and how such similarities occur. For example, is it because of a shared culture, similar life experiences or just coincidence?

I prefer more ironic endings, an ending where the hero loses something to gain his/her victory. But it seems that my heroes lose more than they achieve! If this is tragedy, my answer is yes. Although I believe my endings are not always tragic and I do have happy or at least bitter-sweet endings but my readers think I’m drawn to tragedy.

Genetic ailments are quite frequently used in your work, such as your novel Juliet Syndrome, with inherited infertility resulting from genetically modified foods. Egyptians are pensive about hybridized fruits and genetic engineering themselves. Is this a problem in Iran, hereditary diseases, and does it emerge frequently in literature and cinema?

I don’t see many people talking about this in Iran since we have so many other problems. But it’s a theme that I personally think about. I haven’t seen other writers or artists tend to this matter much. Although if we just stop and look around us, people are constantly struggling with disease and illnesses. We do have so many advancements in digital technology but we still haven’t found a way to cure cancer! I believe that future technological advancements will focus more on biological development to make the human race more immune to diseases, if not try to make superhumans. But these developments may come with a downside and I like to speculate about these unwanted side effects, create dystopias based on them and give a slight warning.

Your story “The Hatching”, about a post-flood world, is very intriguing. Was your story inspired by global warming and environmental SF?

Yes, it was indeed. I have written about global warming in my novel Rain Born in more depth. In Rain Born, the earth drowns after a series of continuous rains caused by environmental change. People live on ships and small islands and they develop a special political and religious belief system. I have a few more stories about global warming like “The Annual Breathing” and my YA novels like The World of Lollipop People. I think global warming and the disasters that follow are closer than we imagine. As a writer, I find that it is my mission to write about it and give warnings in my stories.

The story ends on an ambiguous note, with the hatched bird attacking the hero’s child and abruptly ending. Is this deliberate on your part, leaving us in the dark?

The new born is actually a snake or some form of a reptile. I tried to show this through this hissing sound that the baby snake makes and its description.

It’s interesting that you have birds evolving faster than humans in this post-apocalyptic future world. Why birds specifically? Do you have ‘dragons’ in Persian legend and are they connected to birds? The hatched egg has no arms and legs and slithers like a snake.

Birds don’t have a legendary status in Arabic folklore. We love hunting birds for sure, hawks and kestrels and eagles, but no more. And owls are actually seen in a bad way, associated with graveyards and desolate areas presumed to be haunted by evil spirits. How are owls seen in Persian culture?

We have many mythical birds in Persian literature like Simorgh and Chamrosh that are considered holy birds in Zarathustrian texts. We do also have a myth about dragons or Zahhak which is considered evil. According to Bondahesh, Dragons are snakes at first but they eventually grow wings and become dragons. Perhaps I wanted to show a reborn-world (after the flood) that becomes an environment for giant birds like Simorgh and then show that it can become threatened by other creatures like a snake that has the capacity to turn into a dragon.

In popular view carcasses and owls are seen as bad omen. We have a famous book by Sadegh Hedayat titled The Blind Owl. But Simorgh is the most recurring bird in Persian literature from our ancient poetry (Ferdowsi) to recent fantasy texts.

Is ‘evolution’ a common theme in your stories, and in Iranian literature in general?

Evolution is a scientific subject and is mostly used in sci-fi books. Since we don’t have many sci-fi books I have to talk about my own stories. I have used evolution in some of my post-apocalyptic stories. For example, in Rain Born, there is a mystery plot about new babies that are evolutionized to adapt to their new water environment.

In your novel Death Industry or Death Renaissance you have the Fani Temple containing the quantum supercomputer that can predict how long people have to live, presiding over everything and determining people’s jobs and marriages and where they can and cannot live. The word ‘Fani’ in Arabic means the opposite of everlasting, how life is fleeting. Is this true in Farsi as well?

Yes, it is. It has the same meaning in Farsi and I used it in an ironic way. Since in this story the country is divided into different class divisions based on people’s life spans, I used the name Fani to elaborate on the meaning of “death”. Life is short whether we live a full life or die young and death is inevitable and it is better to appreciate it in any way we can. The predicted death dates in my novel are fixed and considered true in the story, but I wanted to show that even if based on true facts, such discriminations will not be fair. In fact I wanted to say there are no justifiable discriminating systems, even if based on something that all people agree upon.

The world you create in the novel even has a caste-system. Were there ‘untouchables’ in Iranian history?

Iran has a long history of various monarchies and feudalism which automatically creates caste-systems. I don’t have enough information on how exactly this caste-system worked before the Islamic Republic but from what I’ve heard there were always better opportunities for those who were connected to the monarchy. This is still true in some ways. For example, if as a writer you are ideologically aligned with the government, you will receive support and financial aid. But we do have many independent writers and artists (like me) who worked their way through without help and support. Right now, birthright of rich and connected people may be a big stepping stone due to financial advantages and having the right connections, but it is possible for people from various backgrounds to rise.

In my novels I do create class divisions and perhaps this view is rooted on the other discriminations I have felt as a woman living in a religious and male dominant country. Also, I have chosen a career as an independent writer which brings about many difficulties.

Is the evil inventor of the quantum computer based on the ‘mad scientist’ in Western SF?

Mad scientist is another common theme in sci-fi stories. Science fiction is about novum technologies and inventions that change the world and such inventions are usually the works of genius scientist that may have a mad side to them. My novel, Death Industry, happens many years after the death of Professor Fani. I do have a whole plot ready for the life and the breakthrough invention by Prof. Fani but I didn’t bring it in this novel. I was hoping to write a spin off for the book or a few short stories but I haven’t got the chance to do it yet.

The heroine of your novel Humanoid is named Atwood. Is this in reference to Margret Atwood of the Handmaiden’s Tale?

When I first started writing sci-fi, I had a very difficult task of persuading readers to accept Iranian science fiction. Our readers were not used to reading Persian names in a sci-fi, cyberpunk or futuristic setting. They were used to reading translations with Western names. I didn’t want this to push back the readers. I thought of many name systems that could be part of the worldbuilding of the dystopia. In “Humanoid” people have become immortal through the advancements of stem-cell technology. They live long, and every forty years, they choose their own professions. They can also choose their own gender identity and names according to what they want. My protagonist in “Humanoid” is a writer and she has chosen her name to be “Atwood” for the forty years that she remains a writer. The character name “Atwood” is based on Margaret Atwood, one of my favorite writers.

Tell me something about your bookshop, Rama? What do you do to promote authors in Iran? Can an author make a decent living just from writing? From experience in Egypt the only way to promote yourself is through the Cairo international book fair. Is this the same in Iran?

Rama bookshop is specialized in speculative fiction. We only sell speculative fiction books and accessories and comics and manga. We hold so many exciting events in Rama bookshop like book signings, creative writing workshops and we even have a speculative writing contest in winters. We invite authors and translators for Instagram live events and in-person interviews. We have had more than 30 events since the bookshop opened around two and a half years ago. Mostly we prefer to introduce new writers and promote their books. Rama is now a unique community center for speculative fiction writers, translators, artists and fans.

The Tehran book fair is a huge event in Iran. As writers, we are invited to meet with fans and take part in book signings in our publishers' booths. I can't say it is always successful in book promotions. Maybe it is the other way around. If a writer is already famous, his/her books will sell better in the book fair and will have more fans attending their events. In overall it does provide grounds for book promotion since the media focuses on the book fair for two weeks and covers the book fair news, publishers and writers have an opportunity to talk about their new books.

As far as I know, most of the writers in Iran have alternative day jobs. It is very unlikely for an author to make a living from their books. I know some children book writers that earn well or those writers that work closely with the government. But for independent writers, even if their books become best sellers, it will be very hard to rely on the earnings for their life expenses.

On the international front, how lucky have you been with Western publishers? Are they interested in translating and popularizing SF and fantasy from the Middle East? Have your translated novels sold well?

Not so lucky so far. It is very hard to find an agent from Iran that could connect me to western publishers. I have published two books in English. Year of the Tree was translated and published by Candle and Fog publishers which is an Iranian publisher working in other countries. They present the book in international book fairs but I haven’t received much feedback on the book. As for Rain Born I translated the book to English myself and since I didn’t have an agent at the time, I gave it to a publisher that didn’t require agented work. Rain Born was published on January 2020, right on the break of Covid-19 and we weren’t able to promote the book properly. Although the sales on the Persian copy is good, according to the British publisher, the sales outside Iran are low (so far). I don’t know what seems to be the problem. Maybe it is because of the huge competition and the countless western authors that they have, there seems to be no room left for us. There are so many books out there. We must find a way for our sci-fi to stand out and get noticed. We need to find suitable representation for middle-eastern sci-fi and if I knew how, I would have already taken the step!

We need representation but we also need translators that can translate from Farsi or Arabic to English. The western publishers sometimes step back because they don’t have a suitable translator. Sometimes they are worried because of copyright and in the case of Iran, because of the sanctions and the difficulty of financial transactions, they are not encouraged to come forward. But before all this I believe that our books must prove successful inside our own country and in the neighboring countries. For example, if an Arabic or a Persian book becomes a best seller, there is a better chance for western publishers to notice the book and become interested. Right now, in Iran we are just trying to expand readers and I think we have a very long way to go.

Have you published in any other foreign languages, like Arabic or Urdu or German? Have you published any audiobooks?

I only have two of my books in English. I translated my novel Rain Born into English and Year of the Tree was translated by Caroline Croskery. I would love for my novels to be translated to other languages especially Arabic, Turkish and Urdu and I have been trying hard to get to publishers outside of Iran. But it’s a rough path. I hope that one day I could have readers from different countries all around the world and specially from the Middle East.

Many of my books are turned into audio books in Iran. Audio books and podcasts have become popular in the last few years and readers even sometimes prefer them. I work long hours everyday and if I get a chance to listen to something, I prefer music!

Have you read any Arabic literature, SF or otherwise? Is Naguib Mahfouz a household name in Iran? Has anyone in Iran heard of Ahmed Khaled Tawfik, an SF and fantasy writer from Egypt who wrote Utopia, a novel that was translated to English and very successful?

Naguib Mahfouz is indeed a household name in Iran. But we are still unfamiliar with Arabic modern fiction. Unfortunately, the work of Ahmed Khaled Tawfik is not yet translated to Farsi.

From going to bookshops here in Cairo, Egypt I’ve come across a goodly number of Iranian and Turkish authors in translation, but sadly no science fiction from either country. (Turkish soap operas and Iranian movies are also quite popular). Would you encourage Iranian authors to try and get their work translated into Arabic?

The first problem is that we only have a few Iranian sci-fi books. The second problem is to be able to encourage Arab publishers to translate and publish them. I have talked to an agent (Literary Sapiens Agency) and they have presented my books to a publisher in Egypt and some publishers in Turkey. But we haven’t been successful in this matter yet. But I believe Persian books if translated into Arabic, Turkish, Urdu and other neighboring country languages, can become successful. The same goes for Arab, Turkish and Urdu books when translated to Farsi. For example, “The Forty Rules of Love” by Elif Shafak is the bestselling fiction book here. We all share some cultural backgrounds and I believe literature and specially fiction, can form a bridge between cultures and bring people together. There’s so much that I as a reader can learn about how people live in another country by reading an exciting story.

Do you think an audiobook would be more popular with Arab readers compared to a translated text?

I don’t know anything about the Arab market but in Iran, audiobooks are the new trend and the growing part of the publishing industry.

Early modern Arabic fiction, detective fiction if I remember correctly, also had foreign names for characters. And the same holds true of the Polish SF novel Solaris with the hero Chris Kelvin!

On that note, one last question. What do you think we should do to promote our science fictions, at home and abroad? Arabs and Iranians?

First step is obviously translation and publication of our books outside of our home countries and presenting them to the audience when and where ever we can. For example, holding public talks or virtual and online sessions, to talk about the books and ideas and to introduce our literature can be helpful. What you are doing with this interview for example is a great step! I believe the best way to attract attention to our works would be through a successful adaptation! If for example an Arab or Iranian sci-fi is made into a movie or a TV series, more people from all around the world would watch it and if they like it (which I’m sure they will), they will become curious about the author and his/her other works. This will draw so many readers to the books and to the rest of the Arab/Iranian speculative fiction.

For a comprehensive list of Zoha Kazemi’s works and her CV please visit her linkedin page.

This interview was conducted by Emad El-Din Aysha, a member of the Egyptian Society for Science Fiction (ESSF) and Egyptian Writers’ Union and an avid researcher and writer about science fiction. His most recent publication is ‘Arab and Muslim Science Fiction: Critical Essays’ (McFarland, 2022).