By happenstance, I got a chance to watch the Michael Caine classic Get Carter (1971), and then shortly after that David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997) and, funnily enough, you can’t make sense of the two movies except side-by-side.

By Emad Aysha

It sounds strange, but it isn’t, since both movies deal with a related topic, which is the self-porn industry. The opening scene of Get Carter has Michael Caine being shown slides of porn movies made up north, where he originally came from and where his brother was slain.

If you’ve watched the lacklustre remake with Sylvester Stallone, you know that his niece got mixed up in the porn industry and her father was going to the cops, which got him killed. More than that, what drove the girl to this sleazy fate was a lack of attention from her family, including Michael Caine.

As for the thinly veiled protagonist of Lost Highway, the impotent jazz player Fred (Bill Pullman), he is technically married to an ex-porn star whom he’s (quite logically) obsessed is cheating on him.

The voyeuristic videotapes he anonymously receives are also a hint at pornography. When Fred is replaced with the young Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty), you notice his parents are dressed, ridiculously, in identical sunglasses.

They encourage him to go out with his friends, useless misfits, while they busy themselves with watching some 1950s documentary about planting strawberries. The family breakdown is more severe in Get Carter, but there’s no need to go into that.

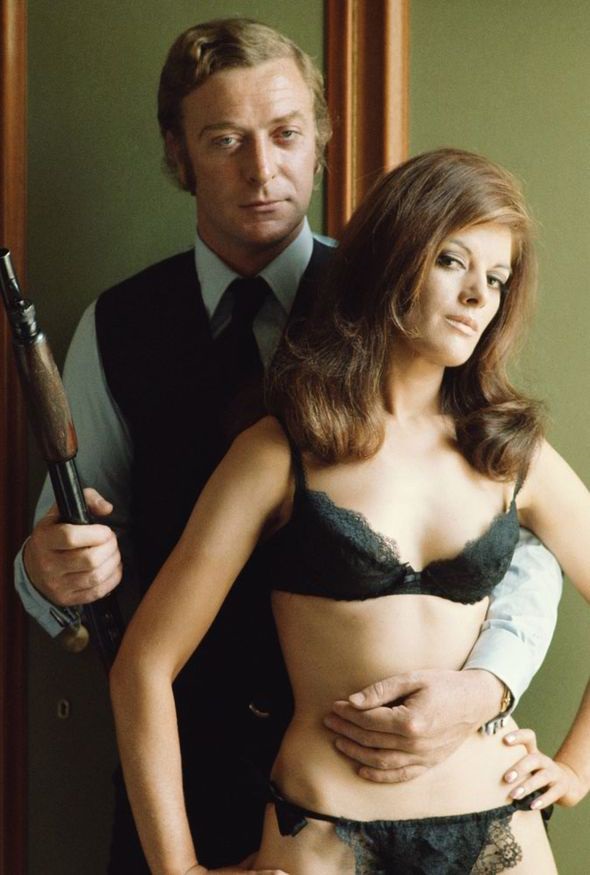

OFF THE RAILS: Michael Caine and Geraldine Moffat from 'Get Carter' (1971). Believe it or not this is one of the less 'loud' scenes in this family breakdown feature.

The Caine movie is also shot in a formidable docudrama-style fashion, showing you life in Newcastle and how people are dissatisfied with old industrial jobs (and family life) and moving into the ‘recreations’ industry if you get what I mean.

Lost Highway has a 1950s feel throughout, from suburban neighbourhoods to cars and furniture, not to mention the scenario with Pete doing it with a blonde version of Fred’s wife Renee (Patricia Arquette), now called Alice, who’s also hitched up with an older dude who treats women like cars.

The upshot is Renee/Alice likes being an object herself, probably not getting enough paternal attention as a kid, and certainly not getting enough attention from Fred and his overcommitment to music.

As a housewife she doesn’t even have a job, and you suspect no education either. Fred is a prisoner of his stereotypes of a happy married life, with a distinctly 1950s hairstyle and taste in stuffy clothes.

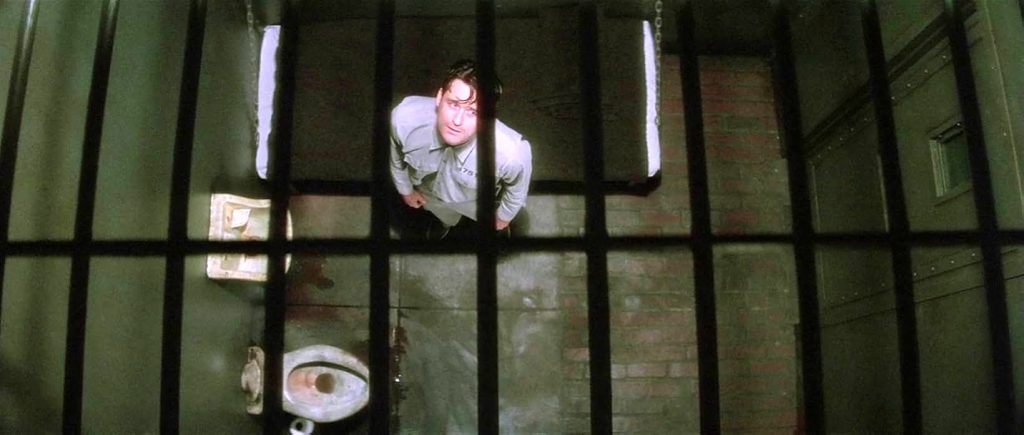

You’ll also notice the parallelism between his prison cell, with the bars on the roof, and the metal sky-view in his home.

Film noir was a 1950s obsession, and Pete is going through a noir scenario, where the girl is constantly ‘using’ him, only for Fred to show up as the so-called avenging husband.

AUDIENCE OF ONE: Bill Pullman as Fred, the jazz player who takes his job 'too' seriously. Well he got what he wanted.

Oh, there are lots of techniques here that overlap with the masterpiece that is Mulholland Drive (2001), such as the bright blue haze that accompanies inward withdrawals – lightning strikes in this movie. (It's a theatre glow).

While I like Mulholland Drive more, I nonetheless think there is something different going on here. This isn’t just self-serving subjectivity but actual mind-bending of reality à la Philip K. Dick.

The cops tell us that they found Pete’s fingerprints at the crime scene of the dead porno king (Michael Massee), and the prison authorities did find him in Fred’s prison cell. He does have Fred’s blurred memories, but he also keeps seeing something like a chrysalis or flower budding in his head, implying that he was violently born to give Fred a way out.

Note the moths? A metamorphosis motif. Fred half-deforms into someone else while in the car on the run from the cops in the closing scene. It’s like he’s in charge of his identity now, not needing a subservient wife or adoring crowds anymore.

David Lynch explained once that the inspiration for the whole came from the O.J. Simpson case, someone who successfully convinced the world he was innocent - maybe after convincing himself first.

There’s also the mystery man (Robert Blake), who wears Japanese mask-like makeup, resembling an Oriental assassin; and others do see him.

SCI-FI PARODY: Patricia Arquette stars in 'Alice Wars, A Rouge One Story'.

Dick often had scenarios where subjectivity didn’t just cut someone off from reality but changed the reality itself, as in A Scanner Darkly and Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said.

The same in David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983), where reality and perception of reality are the same thing. Lynch’s movie also overlaps with Videodrome since snuff movies and S&M are hinted at in the porn scene, the natural product of a saturation of the senses demanding more and more.

Alice to me is Alice in Wonderland, with ‘battling’ realities. (Dick also has replacement character duos as in Time Out of Joint; hence the fat and skinny cop teams, who are all equally envious).

A final note here on cinematography, which gives me yet another opportunity to trash Denis Villeneuve’s Dune. The colours are so potent you can almost feel the lipstick on your mouth, as if you’re kissing everything in the movie, down to the curtains and paint on the walls.

You don’t get that with bland beiges with a desaturation grey tint to everything. Even when you have beautiful images, they’re at a distance, taking you out of it instead of ‘into’ things.

Even with Get Carter, you can feel the griminess and breeze on your skin, the odours in your nose, let alone the physical weight of the violence and the contrasts of lush green and concrete grey.

Even Lynch’s ultrawholesome The Straight Story (1999), a ‘Disney’ movie, greets you with panoramic imagery of agriculture but again in an immersive way since the images move towards you, and are repeated to the point of wonder.

PSYCHEDELIC DREAMS: If it wasn't for 'Dune' (1984) derailing David Lynch's sci-fi career, he may have become the prime mover of Philip K. Dick adaptations.

Why is he showing me this, you ask yourself, using intrigue as a tool of immersion. (Remember William Friedkin’s The Sorcerer). This is all the more ironic given Villeneuve’s own warped noir movie Enemy (2013).

I said it once, and I’ll repeat it: Villeneuve is not a sci-fi person; he just doesn’t know it. By contrast, SF was second-nature to Lynch, but sadly, he didn’t know it. Or wasn’t allowed to!!