I just finished what I presume is an SF novel, Morphius City (2018), by Muhammad Shabaan Mustafa. Immediately I was reminded of the “Cities in Context(s)” AUC Annual History Seminar I’d attended, specifically the science fiction lecture by Teresa Pepe, University of Oslo – “Desert Cities: Environmental and Urban Imaginaries in Two Egyptian Future Histories”.

By Emad Aysha

I wasn’t impressed by the novel. Stylistically it’s good with flashbacks and quite eloquent prose; I finished it in just two days, and its 189 pages long. The author is clearly a cultured guy, with many philosophical quotes and literary references. Still, he’s too smitten with gritty realism and the problems of the here and now to do anything original regarding world-building and plotting.

So much for the misleading title; I thought it would be a dream city with parallel dimensions, cyberpunk technologies, or a steampunk nightmare zone.

At first, you think this is a fictitious world with references to the place being an island surrounded by ocean and a live volcano that could burst at any time – shades of Atlantis or Pompeii. There’s also mention of the virtuous city and overthrowing a foreign occupation.

It’s a pill-popping, half-comatose nation and the poor feed off the guts of cats to the point that the cats have gone instinct. And you can imagine what happens next when they can’t find any more cats and bump into a wealthy person who strolled into the wrong neighbourhood at the wrong time of night. References to zombies, werewolves and vampires are made too.

Then you are bombarded with references to Egypt and its people’s legendary suffering and exploitation, and not long before the end, you discover this is all happening in Cairo. There’s no resolution or proper explanation as to why it’s called Morphius in the closing chapter, which is called Morphius City.

It’s just a cliché and one among many ‘borrowed’ sayings. You have tramadol and heroine and morphine (hint, hint) and a deliberate usage of these drugs to keep people passive, and then references to American Marines policing the posh districts of the rich and taking on the poor to evict them because people in the rich desert cities feel threatened by the expanding population of the poor inner city environs.

Again we’ve seen all this before in some shape or form, with clear borrowings from Ahmed Khaled Tawfik’s Utopia (2008) and maybe also Muhammad Rabei’s Otared (2016), but without the punchline or anything new or alternate to offer.

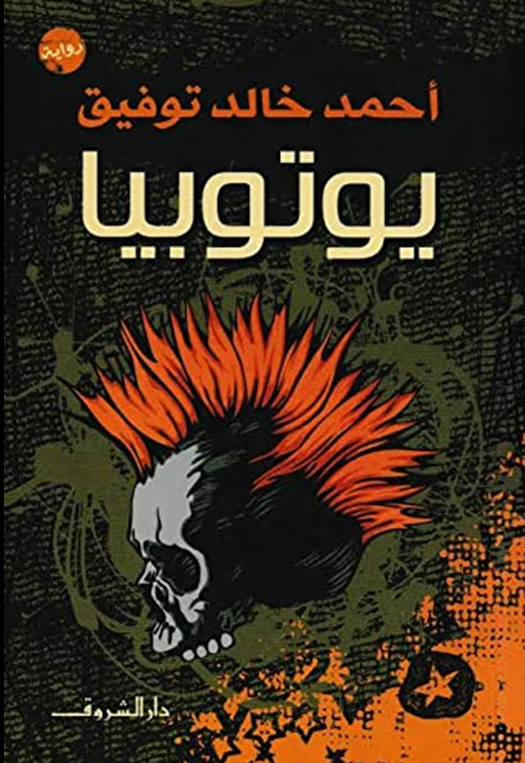

DOWN WITH THE CAPITOL: Check out the not so subtle jibe at excessive Westernisation in Ahmed Khaled Tawfik's modern dystopian classic. [Image from Amazon link]

Even the drugs are mundane and commonplace and don’t seem to lead to anything plotwise since a rebellion does happen without anything changing, so what was the point of the drugs or belated revolution? But, upon finishing it, I remembered the annual history seminar and the ‘repeated’ problems you found with Egyptian urban history beginning in the 19th century, with Khedive Ismail, who ruled from 1863 to 1879. All the cities built looked very nice but were dysfunctional regarding waste disposal, not to mention not being integrated between the foreign residents and the locals, even administratively. (Please see “The Stenches Make You Feel Bad: Bringing Order to the Ordure of Turn-Of-the Century Port Said”, Lucia Carminati, University of Oslo).

That’s the key to understanding the novel at hand and much of modern Egyptian literature, to be honest. The city is not the urban motif for Egyptian writers but the hara (الحارة), neighbourhood or quarter. The hara is a big deal in Arabic culture in general, evidenced by the endless TV series in Syria, for instance, but there’s more to it in Egypt.

Egypt was ruled by foreigners in one way or another from Alexander the Great onwards. Cities were built for these foreigners, leaving the poor to fend for themselves and manage their affairs in their tightly packed, overpopulated neighbourhoods.

Streets in Syrian neighbourhoods are nice and clean, and orderly. Moreover, old traditions live on without being seen as retrogressive or associated with poverty and illiteracy. Not so in Egypt.

Ahmed Khaled Tawfik’s novel begins in a compound, a gated community on the north coastline where all the posh in the here and now live. It’s a ‘hara’ in its own right. The narrator's passage from the gated community to the big evil world outside is a transition from one neighbourhood to another, like the outskirts of town to the inner city.

Note also that foreign security forces protect the residents – the infamous US Marines – while the narrator doesn’t respect tradition. Next to the trashy metal he listens to, he has a Mohawk hairstyle and refers to his father by the man’s first name, not dad or father.

Imperialism ‘is’ responsible for many of our problems, as Abdu Badawi argues in The Meeting of Arabic Architecture with Poetry (1997), with mismatching neighbourhoods and architectural styles developing in the city because of the colonial presence.

The countryside was also marginalised in the face of the city, with a clear emphasis on coastal cities and the capital. Even so, you feel there’s more of a homegrown problem, specifically with the Egyptian experience, with the new administrative and economic elites that replaced the coloniser becoming colonisers themselves.

That’s the backdrop to all these sci-fi works and something to bear in mind if we ever want to put those problems behind us. How ironic that in Teresa Pepe’s paper you had Georgy Zidan’s optimistic vision of Egypt in 2000 with plush open-air villas with Pharaohonic design. Then again, he was Lebanese, people accustomed to clean air up in the mountains.

And Egyptomania was a European fad Egyptians were all too eager to pander to even, in their hearts, so maybe we need our architectural way out of the cultural cul-de-sac we’ve been happy to find ourselves in for way too long!!