by Emad El-Din Aysha, PhD

The shower of His merciful bounty gratifies all, and His

banquet of limitless generosity recognizes no fall. The inner secrets

of His subjects, He does not divulge, nor does He, for a rogue’s

slight frailty, in injustice indulge.

O generosity personified!

To the Christian and the Magi,

You bestow with pleasure,

From Your invisible treasure.

O ardent benefactor!

You will lift Your friends high,

There is solid proof of that,

Not abandoning enemies to die!

--- Saadi

“What is it, son?” the wandering nomad asked. The metal hulk of the… thing glistened in the flaming sunlight of the desert plains.

“It looks like a jet engine, father,” the boy answered.

“A jet fighter,” the man said hopefully.

“Of course not, father. It is just the engine that drives it.” The boy pointed to the sky. They’d seen formations of fighters in the vicinity, heading to God knows where. The last wave, it was said.

“Then we can sell it for scrap,” the Bedouin said triumphantly.

“No, father. I want to keep it,” the boy said defiantly. He passed his hand over the metal casing. It tickled the roughness of his skin.

“To do what? You wish to make a tree house out of it?” They had no trees for a tree house at the camp.

“Experiments!” the boy blurted out without thinking.

He was a bright lad, his father knew that for sure. There was no harm. Another one of those, what did they call them… hobbies. Fads were so hard to shake off nowadays, especially among the young. And if it would keep his son quiet at dinner time, so be it.

His tribe had enough camels to drag this obscenity back with them without exhausting any of the animals. There was no harm.

I mean, what could possibly go wrong?

***

The ‘thing’ was lighter than he thought, like it was made of something other than metal or even hollow from the inside.

His son, Mustafa, insisted on riding it all the way back to their camp. The boy was lighter than a feather so it was no burden. And he made sure the ropes snaring the oblong object were always in place throughout the trip – like a fishnet dragging back a beached whale, and his son a smaller version of the Prophet Jonah, Peace Be Upon Him (PBUH).

“Can I go inside it, father,” Mustafa said. The boy wanted to open it. He had the tools, and the knowhow.

“Wait till the morrow,” his father, Ra’id, said as he dusted himself off. He had other priorities. It was sunset already and they hadn’t had a bite to eat all day long. Lunch was a luxury nowadays. They would have to bunch meals together like they bunched prayers together while on the move. And abbreviated prayers at that, as was the religious custom.

Lunch was fast becoming a luxury for the city dwellers also. The former city dwellers.

Never had the ranks of the tribesmen been so swollen in recorded history. Townspeople were taking to the desert like never before. Well, not since the days of their great father, the patriarch Abraham (PBUH). History was repeating itself in the accursed 21st century, Ra’id was sad to say.

That was why his one and only son was so smart. University professors were rubbing shoulders with the meek of the earth, the very people they disdained and wanted to forget. God only knew what would come of it in the end.

Time to talk to his sister and see what she had prepared for them, in the solar-powered stove.

***

Mustafa awoke in the middle of the night.

He couldn’t wait for the dawning of a new day. He would have his way with the machine before anyone was the wiser.

He snuck out, solar-powered lamp in hand, armed with his toolbelt and his holographic tablet.

He looked around to make sure there were no marauders in the vicinity. They were close enough to the Persian border as it was. This piece of debris was probably all that remained of the Iraqi air force.

Strange, though. The markings on the jet engine, if that’s what it was. They were in ‘English’. Not Arabic or Persian.

Was it a foreign sortie that had been doing all the fighting? It would not surprise him. Their leaders had sold out their land so many times to get others to do their fighting for them. But that did not concern him right this minute. Time to take this thing apart, piece by piece.

Perhaps he could make a solar panel from it. Or a mobile satellite dish. Or a car for the rally races. Or a rocket to the stars. Or a coat of shining armour… Or… or…

The possibilities were endless.

He began to unscrew the bolts that held the thing together.

***

“Boy, what are doing there. Get back here, right this minute!” His father knew where to look. Mustafa’s aunt had woken in the night and found his sleeping place empty. She feared the worst.

His father knew better.

“Father, I am almost fini…” He pried the last bolt loose, only to have that tickling sensation spread all over his body, and beyond.

A halo seeped out of the cracks in the metallic flesh of the thing. The swirling rainbow engulfed them and turned into a whirlwind of blinding light.

***

“Where are we?” Ra’id said, thirsty and terrified.

Fear was the only thing that kept his anger in check, against Mustafa.

They’d woken up, in the day time, their heads rattling like rusty cans – and the camp was gone. As if it had never been there. No traces. No footprints, remains of camp fires, scratches in the sand, refuse, anything at all.

What magic was this? Even a raiding party would leave traces. Tank treads, boot prints. A flag post, shell casings from energy gunfire. The smell of burning flesh. But there was nothing.

They could navigate by night, looking to the immortal stars for guidance. In the day, they were lost. And the desert, it looked different. It was not nearly as ‘desolate’.

There were little grass embankments here and there. And… there were tracks. In the distance. He could see them now. Claw marks.

How could this be? There were only wolves in his day and age, Ra’id thought. Lions, he had only heard of them in stories by the campfire.

And where was that infernal machine?

First things first. They had to get out of the sun and find some fresh water, and fast.

***

“If only I had brought my satchel with me,” Mustafa said as he gulped down another mouthful of water. It was as tasty as honey to his parched lips. And ‘cleaner’ than it should be.

“If only you had not gotten us into this mess,” Ra’id said without acidity. He was too in wonderment to feel any lasting recrimination. There was so much vegetation. This wasn’t an isolated oasis. This was a proper watering hole. There were gazelles in the vicinity. Whole families of them. And that worried him.

Where there was prey, there were predators. And he didn’t have so much as a dagger with him.

***

“Look, father. Tracks!” Mustafa yelled louder than he should have.

They were walking in the wind, meaning they could smell anything ahead of them, while anything ahead of them would not catch their scent.

Ra’id looked to where his son was pointing. Two streaks in the sand. Wheels, and hoof prints. A horse-drawn cart, this far into the century? A fruit vendor, perhaps, one who had lost his way and this far out in the desert?

Every minute here tested his patience. They had to keep moving.

Ra’id sniffed at something.

“What is it father?”

Bad news.

***

The Elders had sent him. Reports had come in of something on the prowl, a beast terrorising their flocks and the camel caravans that fed the city.

This would not do. If the thing tasted human flesh, there would be no end to it. The animal, whatever it was, would never abide deer or goat or even horse meat ever again. A beast worse than itself would crawl under its skin, turn it mad with blood lust. Only man would be suitable prey from then on.

The gods would surely bless whosoever slayed the animal, journeying out into the wilderness where the damned dare to live.

There was only one man for the job. The council beseeched him to at least put on a suit of armour, but they knew beforehand that he wouldn’t listen.

That was why he was the man for the job.

***

Such precision, though Ra’id, looking on in awe at the lion, a wooden point jutted straight out of the animal’s eye.

Beginners luck, thought Mustafa.

The muscular, bearded man with long curly hair, ignored them. He had eyes only for his prize, his short sword by his side, hand hovering over it. He paced slowly towards the animal, bow slung behind his back.

“You should not eat the flesh of carnivores. It is forbidden.” And it messes up the ecological balance, Mustafa wanted to add. “Do you not know the religious edict,” he said, chest pushed out.

Mustafa wasn’t nearly so confident when the lion had come after him. Leaping at them from behind a dune, the boy sheltered underneath his father’s body, only for a whisk that came out of nowhere to save them both.

Who used arrows these days? They went out of fashion with the Apache. Even Bedouins used energy rifles.

“I am talking to you!” the boy said.

“Silence,” Ra’id scolded. The young had no manners, and even less sense.

Mustafa walked up to the man, to his… cart. The man was now bundling the lion into the wooden casket, a pair of stocky horses drawing it. Not Arabians at all. They looked like farm animals.

No wonder the man, a hunter he presumed, needed a bow and arrow. Those poor beasts of burden couldn’t outrun a mule.

A bow and arrow, and a spear – several spears – and an axe, and a mace, and swords, and… they weren’t made of steel. They looked, yellowish, like, bronze. And the man’s attire. His chest bare. The only article of clothing, save his sandals, was a… skirt. Was he from Scotland?! Did the Celts have dark skin and dark eyes and, teeny, tiny curls? And beards with no moustaches?

Surely he must be an Arab, even with his reddened skin? And a Prince among his people, from the way he walked.

“Can you a least take us into town?” Mustafa asked, without pleading.

The man hadn’t spoken a word since he’d made his entrance. Could he not understand what they were saying?

Ignoring them, the hunter got into the cart and prepared to leave, glancing behind him only for an instant.

Mustafa and his father seemed to shrink into the distance before the rickety vegetable cart even got going. That’s how the desert made you fell. Small and alone, if you were unarmed, unlike this fellow with his own offensive toolkit.

As if he could read their recriminations, a curious glint entered the hunter’s eyes. He invited them in with a smile.

***

The man hadn’t been impertinent. He hadn’t been impolite. He just didn’t trust desert dwellers, let alone oddly dressed ones that didn’t have an entire tribe trailing behind them. And he couldn’t comprehend what they had been saying.

He couldn’t comprehend that they were saying anything at all. The words sounded like sneezes.

On the bumpy ride back home, he was able to discern that there were words falling out of their mouths, especially of the young one who never seemed to shut up. Truly, the children were always the most eager to know. Now he knew what his father had felt like when he was that infernal age.

It was strange, though. He didn’t speak their tongue, and they didn’t speak his, but some of the words sounded strangely familiar. Garbled, like the talk of an imbecile.

The dust kicked up by the wheeled contraption they rode hid the city in the distance. When it finally came into view, Mustafa felt sure it was no more than a mirage. He changed his mind when he saw the powerful wooden gates open, like a gaping mouth waiting to swallow then whole.

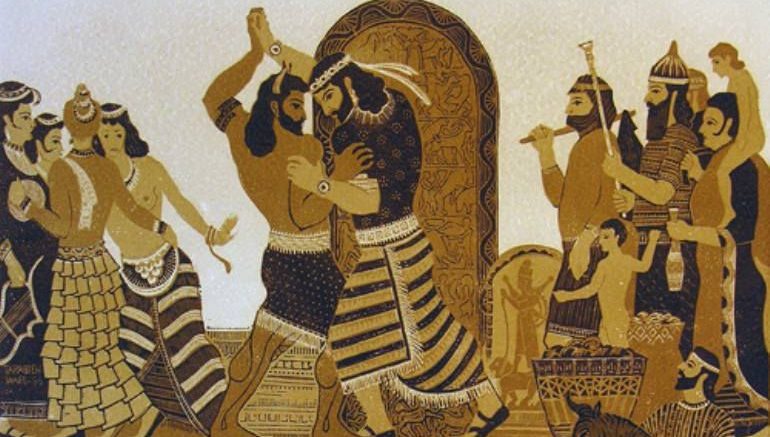

Maidens seemed to emerged out of the alleyways, showering them in flower petals as others girls waved palm leaves or beat away senselessly on rickety tambourines, many of them no older than the boy.

What was his name? Musst-aw-faa, or something or other, the king thought. The boy would like it here. All were welcome within the city walls that he had built, provided they proved that they bore no ill will.

Otherwise they would be skewered on those same walls, an example to all.

“Where are we father?” Mustafa asked in hushed tones.

“How should I know? And what are these mud huts they call houses? Have they not heard of concrete and iron scaffolding?” Ra’id replied.

“I don’t think they have heard of iron, father. Let alone concrete.”

The girls doing all the cheering had tattoos on their cheeks. That was familiar enough. Mustafa could not help but smile back at one of them.

The men all seemed to have beards, whatever their age. Segmented beards made up of those tiny, tiny curls, leaving them looking like accordions at music practice. And the men were all so short and stocky, with pasty white skin and puffy, filled faces like they saw on the American movies.

The man, the hunter, took them to a public square. He dispatched of the lion to what Mustafa presumed were his servants, no doubt to be made into a trophy. Then he made a speech to the gathered folks – there weren’t that many of them, actually, Mustafa had seen bigger towns in his day – and gestured to his guests.

Such an odd tongue. Mustafa was able to catch a word or two that may have been Arabic, but the rest was gobbledygook to him and his father.

Next stop was the man’s house, a mansion by the mud hut standard, serviced by boys and girls.

Going into the place, what impressed them the most weren’t the bronze caskets or shields and swords – more like knives – on the walls and the ceramic tiles on the floor. It was the potted plants. The plant life was always what caught the eye of a Bedouin. Palm trees decorated the city like minarets in their own world, and green fields greeted their eyes in the distance. Life was good here. No doubt the banquet they would be invited to would be saturated with exotic fruits.

***

Nothing but vegetables, unsliced, and the odd pear.

The meats were good though. Roast lamb, goat meat, gazelle and poultry of several kinds that they had never seen or tasted before, and lion meat which the two of them avoided. The man was generous, inviting almost all the menfolk of the town. Not just merchants and holy men and nobles but artisans and farmers and what appeared to be beggars as well. All were welcome in his very humble abode.

The man sat on a pillow on the ground like everyone else. No chairs, let alone a throne. They were no guards posted anywhere, and Mustafa spied a beggar pocketing a small brass plate.

The breads were… strange. They didn’t taste like anything they recognised, and they were too fluffy. And why was there no rice? And no spices. No cumin or curcumin, salt and pepper. How could such a wealthy people be so bland?

The dates were good, as was to be expected, coming in different shapes and sizes and textures, in line with how mature they were. The drinks, in odd shaped goblets like rams’ heads, tasted suspicious. Mustafa’s father sampled them first, then warned his son off. They drank goat’s milk and water instead. Why was there no cheese? Who in his right mind had access to milk and didn’t turn it to cheese? How primitive can you get!

The entertainment was ‘good’ although nothing like what they had in their camp. Dancing girls and singing and chanting, and then those noisy tambourines and strange stringed instruments that plucked your nerves. (Mustafa’s father kept covering the boy’s eyes. He would rather have him cover his ears).

Time passed and more and more eating and conversation and merriment went on, till the day finally came to a close.

Everything that was not eaten was taken outside and fed to the poor – the meats especially – and the livestock (the breads and vegetables) when there was no longer any poor left to feed. Mustafa knew the drill. They had no freezers in this neck of the woods so all would go to waste if not consumed and promptly, and this man was clearly more than a hunter. He was the sheikh of this town, and he could not stand to see his kinsmen go hungry.

He was of noble blood and would rather go hungry himself than watch his people suffer.

Some things never change, nor should they, Mustafa thought gleefully to himself as he went to bed in his father’s arms.

He was going to like it here. Wherever here was!

***

They were surrounded by holy men, and magicians. Surrounding them in a circle, like a human noose. The musky odour of incense filled the air, clinging to their clothes like early morning dew.

Mustafa’s (solar-powered) tablet had given him a wakeup call early in the morning. The buzzing sound hadn’t stirred the boy from his slumber but it had drawn the servants and they couldn’t fathom the three-dimensional images oozing from what they presumed, at first, was a clay tablet.

Now their host was not nearly so welcoming.

He lay at the centre of the circle, in front of Mustafa and Ra’id, sitting atop yesterday’s prize, the lion pelt. The beast’s head pointed toward them, fangs as sharp as daggers, like the first time they’d seen the animal. Leaping towards them with all its fury and skill, only to be felled by… The cross expression on the hunter’s face cut through all the mists of language men could muster. He felt betrayed, that these guests were spies sent here to deceive him into exposing the city’s defences. They had caused him great embarrassment. Mustafa could tell all that in an instant.

If only he could communicate with them. They would see it was all a misunderstanding. How do you say ‘tablet’ in their tongue?

The tablet, that was it.

Mustafa needed a written sample of their language so he could look it up on the machine and find a basic vocabulary to bring them together. He knew in his heart of hearts that they spoke a common language, but that time and distance had driven their vernaculars apart.

He walked up to the sheikh of this town, their generous host, and showed him the machine. He scrawled some words on it, from right to left in Arabic. A sparkle in the man’s eyes eased the set of his features. He understood. His people also wrote from right to left, although he couldn’t recognise the connecting letters of the Arabic alphabet.

He called out to one of his servants. Not long after he was presented with a clay tablet and a wooden stylus, a writing instrument, and he scrawled some letters down on the still wet clay.

“Father, it is cuneiform!” Mustafa yelled out.

Cuneiform? Ra’id couldn’t believe his ears. No one used that anymore in modern-day Iraq. Assyrian and Chaldean Christians still spoke their ancient tongues in some isolated quarters of the country, but even they used a script that was close to Arabic. Nothing like this, the oldest non-pictorial written language in the world.

The boy looked up cuneiform on his tablet on the phonetic library and drew up a pronunciation set for equivalent terms and sounds in Arabic. But he would need his father’s help. Maths and engineering was Mustafa’s strongpoint, not poetry and oration like his father.

“Come, father, there is nothing to fear. We are here among friends. Our own people.”

Ra’id took a tentative step forwards towards their host, a man who now looked more like a learned scribe dutifully taking down his master’s lessons than a slayer of beasts, or ruler of men.

***

The holy men had cleansed them with herbs and holy water, mumbling their prayers, while the magicians read spells and threw carved objects around them to ward off evil spirits.

They tried to persuade their king to leave this house and take residence elsewhere, till they could be sure these two were ‘safe’, but the man would have none of it. He faced his enemies head on. And he refused to believe this man and his tempestuous boy were enemies. They may be blessed by the gods, or cursed, but they were not enemies in his book.

Mustafa magnified the holographic projections of Arabic letters juxtaposed with their equivalents in the man’s language – it turned out to be Akkadian – and got his father to pronounce the letters, and combinations of letters. When all else failed, the boy would use the visual database of his tablet and show the king images of things and get his father to say the Arabic name, while the king spoke the Akkadian.

Their languages weren’t too different after all, as both sides had suspected. They had common root words and a similar vocabulary and grammar and even similar expressions. Arabic was more sophisticated and refined, Akkadian more guttural and straight to the point (much like they’re annoying music) but had enough meeting points for the average Akkadian and average Arab to get along without finding themselves at each other’s throats.

Writing was another matter completely. The words Akkadians used were as segmented as their beards. And their mathematics was exhausting.

The sun was on the verge of dropping out of the sky. So much the better. Mustafa had requested astrologers so they could compare notes. His father knew the constellations by heart and his son had an astronomical database uploaded onto the machine that would help them figure where and, more importantly, when they were.

***

“We are that far back,” Ra’id said, gobsmacked.

He had no idea jet engines could go backwards in time. No wonder so many planes had disappeared over the Bermuda Triangle, he thought to himself.

Mustafa knew better. That was no jet engine. It was some insidious weapon the Americans had devised, in a half-hearted effort to help out their allies, the Iraqis, in their latest great war with the Persians.

The only thing that left him dumbfounded was how the hand of fate had taken them back here of all places, in the presence of a man and a place of legend. Kilkaamesh – as they called him in classical Arabic – of the city of Uruk. This was no coincidence, in Mustafa’s reckoning.

He was the man of their dreams. The man who would turn things around. If only he could get a Youtube linkup and show him what was happening to his beloved land, in their time. They could change everything.

***

“What you speak of cannot be,” Kilkaamesh said in his heavy Arabic.

“But it is. Look at us. Look at this.” The boy gestured to the tablet. It was the following day and Mustafa had recharged the device in the sun, when the clouds allowed for it.

“Magic,” the great man said in defiance.

“Science,” Mustafa said in equal defiance.

“They are one and the same. We look at the stars to see the future, and you are from the future. Or so you say. And from a time... I cannot imagine that the world will last so long.” Would there still be air to breathe that far in the future? Would it not be all used up by then? And surely the land would turn barren and the water evaporate into the air, the soil turn salty, the crust of the earth turn flaky, and the animals and plants and… people, degenerate into pigmies. How could these people, from the future, be so tall and sinewy compared to the prime stock of men that existed now?

In truth, Ra’id was thinking the same thing as the great king. He had been brought up on legends that once giants walked the earth, that Adam himself was a giant, and that the people of the past lived in gold palaces and drank from rivers of lime and were surrounded by sands made of rubies and pearls. Things that clearly weren’t true in this time and age, as plush as their lives were. Even their gold rings and bracelets looked like copper wires and their clothes were not nearly as comfy as they looked.

He’d tried their clothes on and all he could do was ‘itch’. They, on the other hand, had investigated their garments with wonderment, simple Bedouin clothes – Made in China – were so smooth to their touch and knitted in intricate ways they could not fathom. It convinced the priests and fortune-tellers, again, that they were phantasms from the other world, where owls swooped down on you and snatched away your soul, dragging it down to the land of shadows.

The King was still thinking it over. And of what they had told him, of their world.

Their country was a diseased carcass lying in the desert, being pecked apart by vultures, the land’s own neighbours. And not just those who spoke with different tongues to them. He could not imagine such a fate. What accursed species of people would put up with such dishonour? Were there no men in this other age? He would lay down his life for his people, and they for him, and together they would ward off anyone who dared dream of threatening the city.

What they spoke of stretched credulity. But where else could they come from? And it wasn’t just the clay tablet that the boy wrote on. He had an orb with him that glowed in the dark but that immitted no heat, and was made of a silvery metal they could not recognise. And tools of the same metal that could take apart anything metallic.

What phantasms were armed with metal? What phantasms needed to eat and sleep, and needed the power of the sun to power their magical devices?

Phantasms drew sustenance from the dark. Everyone knew this.

What to do? What could anyone do?

***

“I will not attack my neighbours for something they may or may not do, in the future,” the king said hoarsely. That was a coward’s act.

“But they will attack us. I have told you th…,” Mustafa protested.

“There is no set fate. You said this yourself,” he chided.

The boy, to his credit, had convinced him of that. At the very least. What had the boy said?

There is only one God and He left fate an open book for us. If He had ordained it that the future could not be changed, we could not have made this trip. Your future is our past, just as our future will be the past for those who come after us. The Lord above guides; shows us the right path, but no more. ‘We’ are the ones who have to walk it.

The boy was wise beyond his years, if a bit too driven.

***

“Can we at least convene a council of war?” Mustafa was at it again.

A look of understanding moved between the Bedouin and the King. They were ages apart but fathers had to endure the same in all ages. Wars were invariably fought by the young, in service of the old.

Time to educate the boy into the never changing ways of the world.

“Young Mustafa, come here.” He patted his knee.

The young boy looked at his father. Ra’id nodded his permission.

Mustafa climbed onto the man’s knee. He felt so unworthy.

“Ask me a question,” the great king said.

“About what?”

“Why did I build the great wall surrounding us, my beloved city?”

“To keep the lions out,” was all Mustafa could think to say.

At that Kilkaamesh laughed. It was refreshing to see that laughter, along with sounds of anguish, had not changed, however far back you went. “In a manner of speaking,” he said at long last, after regaining his bearings. “I built the wall,” the emphasis on the word ‘I,’ “to keep the lions in.”

“I… do not understand, great king.”

Another glance between Kilkaamesh and the boy’s father. Ra’id, as a Bedouin, understood all too readily.

“I am king, that is true... a sheikh, as you say. But even the king only has so much leeway in his job. I was anointed by the Elders to keep the peace, and fight all our enemies. But I can tell you this. Not all our enemies lie beyond the city’s gates. There are those who imagine enemies where they are not, and expand and consume more than they can, till their bellies burst. And they would expend all our resources, and the youth of our city, to no avail, chasing ghosts that exist nowhere save in the darkness of their own hearts. A wall is there is to keep a man’s ambitions within a man’s reach.” He paused, recollecting the boy’s own words, then added. “The fate of the world may not be set, but that does not mean we can decide any fate that we like. The test of a real man is to know his own limitations.”

Mustafa almost burst into tears. He schooled himself into submission then spoke. “Then can we build a great wall, round my country?”

“From what you have told me, it would do you no good in your time. You have metallic chariots that can fly through the air. And slingshots trailing fire behind them that can carry over any wall no matter how high.”

“Then, what can we do?”

“The first rule of combat, is to never take on an enemy you know you cannot win. There is no dishonour in withdrawing from the field of battle.”

“That is the Bedouin’s way, my lord,” Ra’id said.

“Then what are we supposed to do, tunnel our way under the ground?” Mustafa said stupidly.

“Nothing so dramatic. You know of my other building project?” The man, the king that he was, winked at him.

Mustafa knew precisely what he was talking about it.

***

Ra’id was terrified by what he saw. How could something be so big?

He felt like it was swallowing him whole, the ground beneath his feet turning to putty. He’d read about it in books, seen picture of it on the holovision, but nothing prepared you for the enormity of it.

His son knew better. They were only in a frog pond compared to what lay ahead.

They were going to become a whole new kind of Arab.

***

“Are you sure this will work, great king?” the Bedouin asked, for the umpteenth time.

“We have no choice but to try. And do you think it is a coincidence that the device that brought you back here did not come with you? Denying us the only way of knowing? What can journey with you backwards surely can take you forwards.”

Ra’id didn’t know what to say.

“You are a nomad. Look at it this way. Is the camel not the sailboat of the desert?”

Ra’id nodded.

“My ancestors came from the desert, because their ancestors took refuge there from their own arrogance. Squeezing the life out of the land as they did till they turned it into the very desert they were trying to escape from, like their own ancestors.” The follies of man were a bottomless pit.

“Then why not head into the desert again, my lord?” Ra’id said. “It is a safer bet.”

“No, we need to surprise the enemy, once and for all.” And if you stay in the desert for too long, with no clay to write down what you have learned and where you came from, you forget who you are – becoming a beast. Kilkaamesh kept this all to himself. He did not want to offend his Bedouin friend.

“Then why are we going behind the backs of the council of elders,” Ra’id asked.

“Because they would not understand, fight the decision by tooth and claw, or rat us out to our enemies.” Kilkaamesh shrugged his shoulders. They had that gesture, even back then. “It is no bother. I am not breaking any law set in stone.” Thank heavens we use clay, he added silently to himself. Any man-made rule can be re-written if the clay still hadn’t met the kiln.

“But your legend, great king?”

“That is the road to any man’s downfall. Let them spread lies about me, my arrogance, my challenge… affront to the gods. I have done my part. No city is forever, though it pains me to say. I will search for greener pastures abroad, and carry with me the people who are willing, of their own free will, to join me in the unknown.”

“Where is our first stop, great king?”

“You are the pioneer, Ra’id.” Kilkaamesh’s Arabic was getting better every day. He was using the proper meaning of Ra’id. “I trust your judgement.”

“I trust my son’s judgements,” Ra’id replied humbly. “He was the one chosen by the hand of fate, as his name portends. My wife died in childbirth, and it was always her wish that her son – she was certain it was a boy – be named after the… er, our Prophet.” Mustafa, from safwa or ‘the selected’, was another name for the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). “The young will always lead the old, in the end. They are the future. We can only help guide them, with the help of the stars,” he added for measure.

“And your son’s tableted maps,” the King finished for him.

***

“A Bedouin is a scavenger,” said Mustafa proudly. He adapted to the wooden monstrosity they were now riding faster than any of them, even the King. Seasickness did not differentiate between ruler and ruled, any more than a lion did. “I say we save what can be saved before the ravages of time destroy all records of like-minded great peoples.”

“And so, where exactly is our first stop,” Ra’id spat out. His stomach couldn’t handle any more riddles. His preference was for India, to get some much needed spices for their stocks of boring foods.

The boy tapped away on his tablet till he found the map he was looking for, blowing it up out of all proportion.

“Persia,” Kilkaamesh said in wonderment. It was the last thing he expected from such an energetic boy.

“Elam, to be precise,” Mustafa said triumphantly. “And ahead of schedule, long before the Assyrians have a chance to destroy it!”

Epilogue

A young man in the war college in the 22nd century sat at a table by himself, leafing through the parchment pages of the Kilkaamesh annals. They chronicled the exploits of the diaspora of the city of Uruk, dispersed across the world in a feat of migration the likes of which the world had never seen before or since.

Boats as great, or greater, than those built by the Phoenicians with deep hulls to store food and water, making their way to the four corners of the world, building a maritime empire connected by trade and language. They didn’t do anything, however. They didn’t disturb the peace anywhere. They’d didn’t play along with the game of nations. They just kept to themselves, no different than Chinese merchant communities round the world, working away in silence.

It was like they were biding their time.

They’d only come back to rescue their homeland – they’d ignored them all those centuries, millennia, as if fearing to change the course of history too soon – and saved the whole of the old, old world.

Not through violence, mind you. Through a balance of violence, and creativity. They were merchants alright, but merchants with a mission. To buy what other nations had to offer, in terms of knowledge and traditions, devising inventions on board their longboats, all carefully concealed from the scientists of the world who would pervert that knowledge to military gain.

Without a shot being fired, they liberated their homeland from foreign interference, and reenergised its population and its civilisation, challenging their neighbours in a game of wits and invention. And just in the nick of time too.

Another American bomber had been dispatched, a stealth bomber this time, with a second deadly payload. (The files had only just been declassified). A time-displacement device. Meant to undo whatever… whoever got in the path of the powers that be. Disappear them from history, and all their achievements, wrecking the whole of history in such an old and fateful part of the world as the Near East, the beating heart of the world.

Only Americans would be arrogant enough to do such a thing, thinking that history had happened before them and therefore was no concern of theirs, would not affect them. He knew better.

If the bomb had been detonated in Iran, as was intended, there would have been no Cyrus the Great and his universal declaration of human rights and religious tolerance and equality. If the plane had crashed, as the previous one had within the (wobbly) Iraqi border, then Gilgamesh and Hammurabi and aqueducts and the 24-hour system and astronomy and the harp and atomism and all that would have been swallowed up.

With the Iranians being held at bay, the stealth fighter was recalled and the time-displacement project discontinued, and the treasure house of historical memories that was the land between the rivers was preserved forever more.

That’s when history began to change for the better, everywhere. The diaspora of Kilkaamesh (or Gilgamesh as he was originally known in the West, till his descents set the record straight) worked their way from the Middle East outwards, using their detailed knowledge of what actually happened at the time of David and Solomon (PBUH) to put an end to the claims of the Zionist colonisers once and for all. They went from peace brokers to liberators to custodians of the public trust, with historians far and wide flocking to their shores to drink from the wellspring of ancient wisdom that had risen once again. There were paper manuscripts from the House of Wisdom (including Mani’s once banned picturebook) and from the bookshops of Samarkand and Bukhara. There were papyrus scrolls from the Library of Alexandria – which hadn’t been destroyed by either the Muslims or the Copts – from the chronicles of the priest Berossus (the world was much older than we thought) to the secrets of mummification and ancient Egyptian medicine to the full texts of Democritus and Thales and Aristarchus. There were the lost works of the scribes of Machu Picchu and Nalanda… all were destined to be dusted off and rehabilitated for all to see. The world had finally risen from its long forgetfulness, never again to return.

That’s why he’d enrolled in the war college. The Texas war college. To learn from the past, on how to avoid wars, and prevent another temporal confrontation, this time between the ailing US-Canadian caucus and the resurrected Aztec-Inca federation to the South.

Texas was the frontline, another wobbly desert frontline, and he was going to save peoples on both sides of the border an awful lot of trouble. And he knew for a fact that he was the man to do it.

They’d done a DNA check when he’d first enlisted and identified his line of descent, finding trace elements of Akkadian and Arabic blood. A combination as original as the mix of Arabic and cuneiform in the great book he was reading, the new lingua franca of the civilised world.

The knowledge of this noble lineage, the weight of the responsibilities, had grown and grown in him. No different than the storehouse of knowledge the diaspora had accumulated from all the civilisations they’d encountered, before those civilisations fell to either conquest, pestilence, natural disaster or civil strife.

It was in his blood, to make his own fate.

The Arabic version of the story: http://arabiyaa.com/2019/03/03/%D8%B2%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%A8%D8%B7%D8%A7%D9%84-%D9%85%D9%84%D8%AD%D9%85%D8%A9-%D9%83%D9%84%D9%83%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%B4-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%AF%D8%A9/?fbclid=IwAR1k1smunbYXqxuA_LjjxxjDggntsvTHuMk2t9vYLbWUSlkdS9MQzNdplRc

[…] history, what’s been written about it in stories and how – and try to fix it. Hence, my story “Demigods in Time”, a time-travel epic where I go to great lengths to correct how Gilgamesh was presented in […]