You can’t talk about cinema without talking about show-do-not-tell. It’s a truism, but it can also be taken too far. We saw that, tragically, in Furiosa (2024), where Anya-Taylor Joy was consigned to the inexplicable silent treatment. We’re not told why she keeps quiet, and she’s got no reason to keep quiet. That being said, the concept of show-to-tell is still valid… as hell!

By Emad Aysha

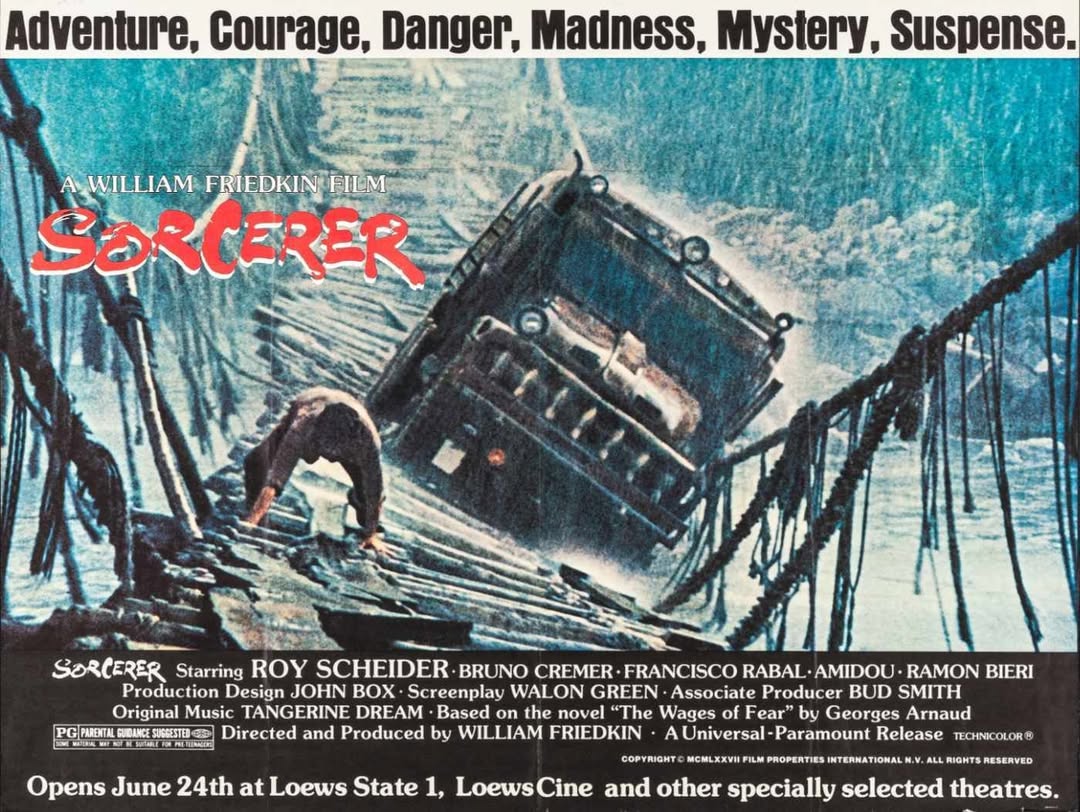

I realized this after watching an overlooked masterpiece by William Friedkin, eponymously named Sorcerer (1977). It's over two hours long and inexplicable as can be, with a diverse set of characters from all over the world thrown together in some destitute, made-up Latin American dictatorship. Different professions, different people, different problems. And with all of that it works, wonderfully.

Terrorists blow up an oil rig and with the shitty resources the US oil company has its disposal, they are forced to rely on sticks of dynamite that have long passed their sell-by date. But how can they get the explosives to the oil fire to put it out? It’s a suicide run.

The characters enter the fray. An American getaway driver hiding after a failed heist with a price on his head, a French fisherman turned bigwig who leaves his upper crust wife after his bank goes bust, a youthful Palestinian bomber, and an even more inexplicably a Latin American hitman. (You thought at first that the mafia hired this guy to go after the getaway guy, but instead he murders one of the truck drivers to join the group).

SCARE FACTOR: William Friedkin of the set of the 'The Exorcist' (1973), still one of the best horror movies ever made. (Makes you wonder who the actors were really terrified of).

Again, the genius of the movie, almost in every single scene, is to not tell you anything. The pictures are allowed to fill in the blanks, and my God, are the pictures brilliant. They are almost silent images with excruciatingly detailed panoramic shots of places and the people inhabiting them.

This includes fancy restaurants, behind-the-scenes boardroom meetings, markets, slums, and landscapes the heroes must traverse to get the decayed dynamite. The weight overwhelms your senses, and you 'feel' the movie more than you think it.

The Frenchman, for instance, tries to get an illicit ticket to leave this hellhole of a country, pawning off a gold watch (an anniversary gift from his wife). When he gets the dynamite mission, he doesn’t need this anymore, and an old lady gives him back the watch. The American getaway driver likewise buys a drink for the Frenchman, having heard that he once ran a bank (into the ground).

The American even befriends the hitman at a key juncture in the story, when the guy saves his life from would-be rebels (who are really just thieves in disguise). The closing scene shows the American, with the prize money and ready to leave, insisting on having a dance with that old lady, also with a letter left by the now-dead Frenchman.

This is not so much honour among thieves but the camaraderie of the miserable. There’s a dignity to being beaten down and having no lower to go. Even the Palestinian terrorist uses his skills at one point to clear a path for the trucks, risking his neck in the process.

I wish I could say the story ends happily because it doesn’t, but it’s still a brilliant movie, in part because of how inexplicable it is. We still don’t know why it’s called Sorcerer when there is no magic or witchcraft here.

The visuals that are painted out of goo, the tense and existential music, and the incredible odds these hapless individuals have to traverse, wins you over to their side and engrosses you in the movie to the point that you think you’re there with them in the middle of all the mud and shit and bullets. (Some scenes are so stressful you almost have a heart attack!)

There’s also a fair amount of world-building here since what sustains a world isn’t the big picture, the broad brushstrokes, but the side details, yet another part of show don’t tell. And that’s precisely ‘not’ what you get in Dune part one (2021), as you may have already guessed.

There you have clichéd music filling in for emotions and spaced out imagery (and facial expression) that are so damn far away you need to squint your eyes to pick on any of the details.

A movie can and often should be like an art gallery, but galleries work best when there is a hubbub in the background, people chatting about themselves or the works of art, and a sense of smooth and logical transition from one painting to the next. Not an eternity between one sentence and the next.

Moviemaking evolves and conventions come in the form of waves or cycles. It seems Hollywood has got itself into one of those cycles where you either have too much exposition or not enough – or both, in the case of Dune 2021.

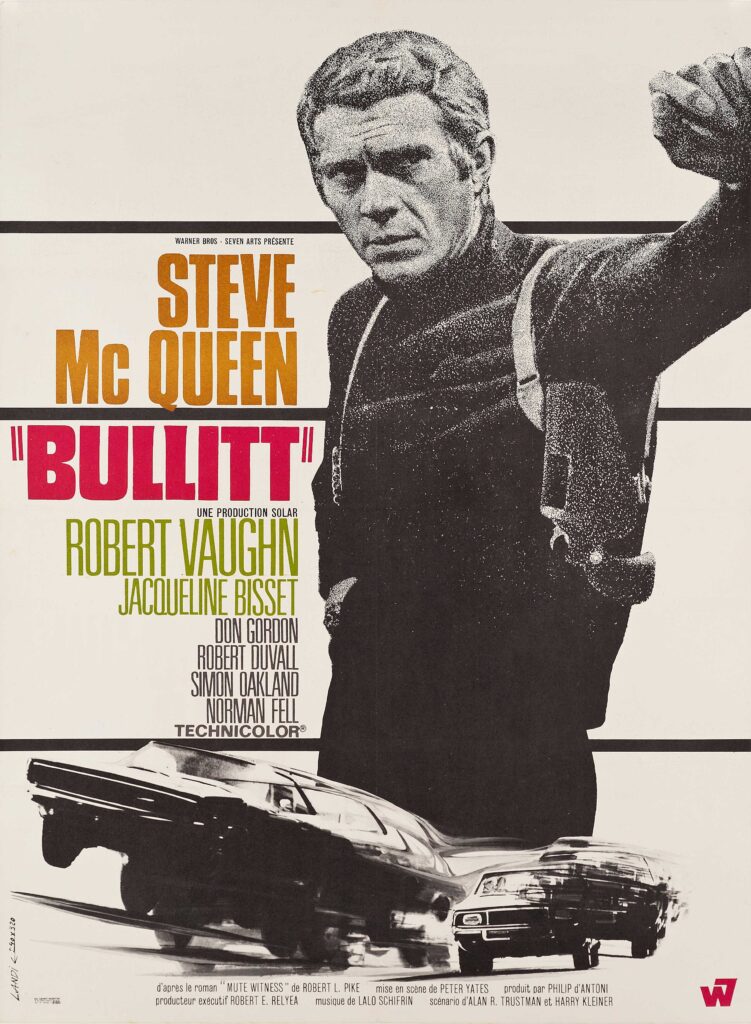

If you watch Steve McQueen’s Bullitt (1968), you also have this docudrama mode of filmmaking where you hear murmuring in the background with lots of panoramic shots and unanswered questions along the way. Essentially, you see Sorcerer, but in a more glitzy and action-packed fashion. However, the common thread between both movies is that they are thrillers, so you must intrigue the audience by not revealing too much and filling in blanks implicitly.

KINGS OF COOL: The 1970s is an increasingly lost era when it comes to docudrama cinema that is real but entertaining. Today's livestream just doesn't hit the spot.

That’s the difference between a good director and a great director, adapting his style and expectations to the demands of the genre in question. It's also testament to the freedom directors had back then compared to now where insecure studio execs simply don’t trust the audience to ‘get it’ unless they’re clobbered over the head with too much, or too little exposition.

We need a sorcerer to resurrect you-know-who, to replace you-know-who!!