By Emad El-Din Aysha, PhD*

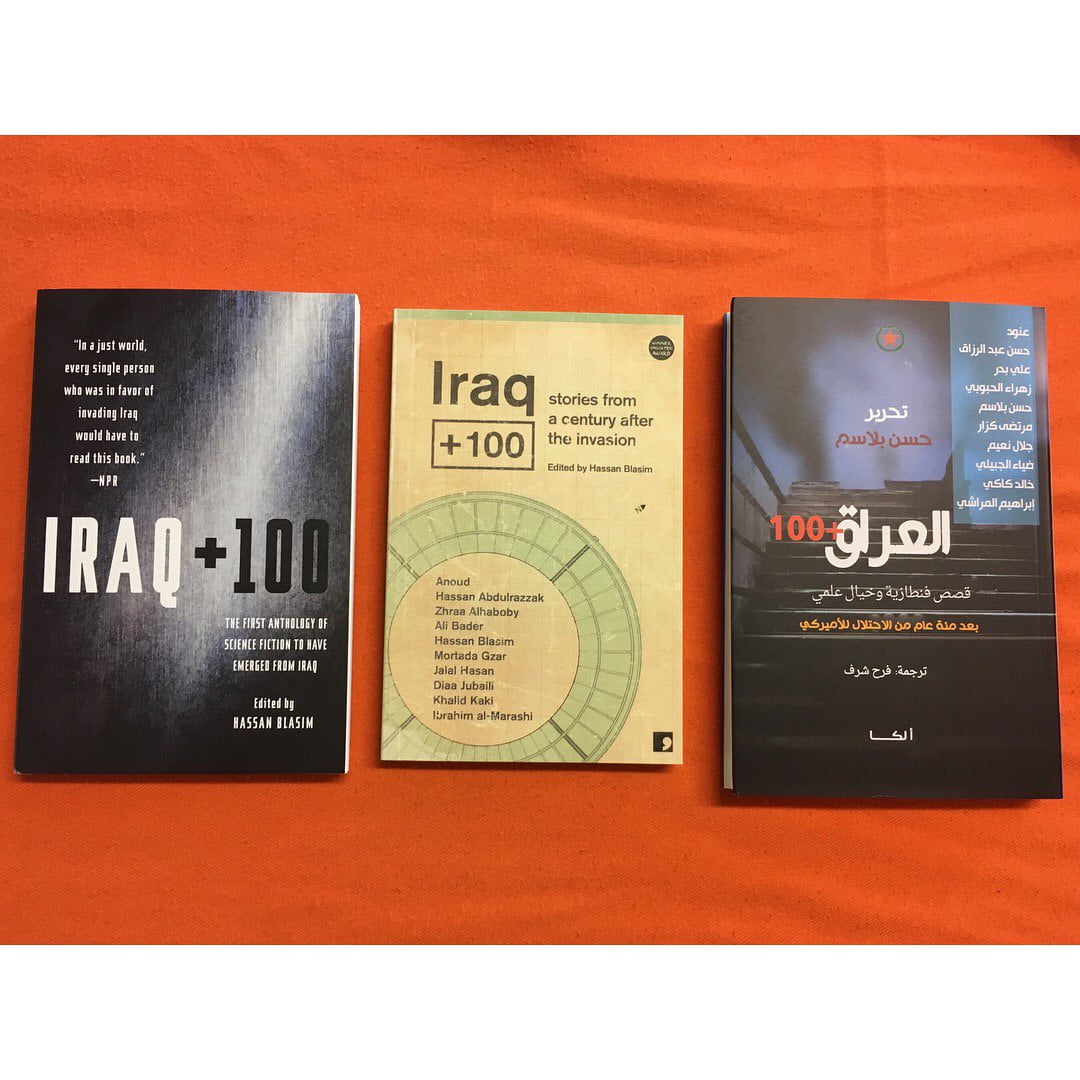

What can we say, off the bat, about Iraq + 100, published by independent UK-based publisher Comma Press in 2016?

Well, first of all, it’s a brave attempt by a small publisher to establish Iraq in the field of science fiction, a genre that has not always been amenable to Arabic literary tastes. The book was the dreamchild of distinguished Iraqi poet and author Hassan Blasim and Comma Press editor Ra Page and it was good for them to set down the agenda, as it were, to a group of Arab authors that may not automatically be inclined towards science fiction. The challenge laid down to them was to imagine what a future Iraq would look like a whole century after the American invasion-occupation of their homeland in 2003.

The second thing that can, and frankly should, be said from early on is the quality of the translations. Iraqis have their own dialect and Iraqi literature is tough, even for a native Arab speaker and amateur literary translator like me, let alone for Western translators schooled in classical Arabic. The vast majority of the stories were written originally in Arabic, even by those authors that are expatriate Iraqis and may have grown up abroad.

The third thing that can be said is that, while each contributor brings his own distinctive touch to the subject matter, there are some common threads that unite them all. Apart from violence – personal and political – and the perennial concern over keeping the country united, there is also the issue of history. Each one of the authors is trying, in his or her own way, to ‘maintain’ the past and often by reconstructing it. They are all aware of just how old and grand Iraq is in the annals of time and the contributions its’ made to human history – science, technology, religion, literature, language – but they are also aware of how the American invasion has threatened to wipe the slate clean of these memories of grandeur and national identity. This might not have been intentional on the part of the Americans, mind you, but with the destruction of archeological sites and the pilfering of antiquities, and separation of families and death of whole bloodlines, you can’t help but notice how the authors are trying to hold onto the past in their own lives, let alone in the worlds they create here.

It is one of the most endearing aspects of the anthology and may not be a theme immediately evident to the foreign reader. History means ‘intimacy’ to these authors, stories of families and lineages and journeys back to their ancestral lands, and comparisons between past, present and future.

Now for the gory details and all the critical stuff!

Footnotes in the Sand

“Kahramana”, by an anonymous author who goes by the nom de guerre Anoud, speaks the tale of an Iraqi beauty (Kahramana) with sea blue eyes escaping an arranged marriage with a petty despot in a fractured Iraq. She makes it into another zone of the divided country, still run by the Americans this far into the future, and despite all the pretenses of the Western world towards upholding the rights of oppressed Muslim and Third World women, she gets evicted on a legal technicality. She becomes so distraught that her eyes turn black and her hair turns grey, to no available. The border guard who let her through the first time has more important things to do – such as job security – to notice her plight, leaving her to die in the cold. (The Americans tried to sterilize the Islamic empire through a bioweapon and ended up causing a small ice age in the country instead).

“The Gardens of Babylon” by Hassan Blasim (and translated by Jonathan Wright) is about a prosperous and peaceful future Iraq in a corporate dominated world where ethnic conflict is a thing of the past. The country is without natural resources – the oil ran out – and the ecosystem has fallen apart, but Iraq is thriving nonetheless because it has become a high-tech haven, exporting software solutions and smart books to the rest of the world on the model of India and Hong Kong. It is in this cheery, and libidinal, context that a programmer/author tries to recollect the past of a long forgotten Iraqi author who committed suicide in his prime as feedstock for one of his smart books. In the process he relives the past, draws the best out of it and reconnects with his own past as an Iraqi, without losing track of all of the benefits of the modern world he now resides in.

“The Corporal” by Ali Bader (translated by Elisabeth Jaquette) is a satirical and quite blasphemous piece about a corporal who was killed just after the American invasion – he got shot through the head by an American sniper while surrendering, going for his pocket to give him some nice flowers. The man makes it back to Iraq a hundred years in the future by divine caprice. While at the gates of heaven he spies Socrates arguing with the Almighty about a better way to covert people to the word of the lord, which is by resurrecting a dead person to tell people about the afterlife. The said resurrectee finds a God-loving future Iraq where people don’t need religion anymore because they’ve learned to put their differences behind them and appreciate God directly, each in their own personal (and sexually liberated) way.

“The Worker” by Diaa Jubaili (translated by Andrew Leber) paints a harrowing portrait of a future Iraq, divided and sapped of all its natural wealth, where armed gangs resort to the slave trade and cannibalism to survive and prosper. Meanwhile, the Mullah in charge of the town in question uses (or abuses) history to keep himself in power, using personalized accounts by people long dead and gone talking about how things were worse in their day. To balance the budget, the Mullah has all the bronze statues sold off, condemning them as pagan-worship, when in fact they are statues of great and good people in Iraqi history. One of them, it turns out, is the said worker, who ends up smuggled and sold to a museum in the West, one of the few places where they appreciate the archeological past, evidence of what happened to Iraq as a consequence of the American invasion. The story is told from the point of view of this man who is also a statue, the indestructible Iraqi everyman who has seen it all and still perseveres – an example to all.

“The Day by Day Mosque” by Mortada Gzar (translated by Katharine Halls) is a garrulous tale of a future Basra facing shortages of everything except snot. They have a National Snot Bank and no shortage of people who empty their nasal cavities whenever they watch TV, seeing the Day by Day mosque in the background, built by an expatriate Iraqi from England. I presume the title mans that, in this terrible world all you can hope for is to live everyday as if it was your last. Most of the story focuses on a member of the Day by Day clan, named Salman, who has a nervous tick and deformed neck – a stand-in for the crippled country that Iraq now is.

“Baghdad Syndrome” by Zhraa Alhaboby (translated by Emre Bennett) is about an architect in a fairly well off future Iraq who is slowly going blind. He’s haunted by recurring dreams of a women calling out to him in pure verses of poetry, an all too common affliction suffered by many residents of the capital city who have a rogue mutant gene in their DNA that robs them of their sight, so-called Baghdad Syndrome. Through a trick of fate, however, the architect discovers that the dreams are actually memories of two lovers who had their own dreams dashed by war – the destroyed past calling out to those in the present who can help reclaim it. The women, not coincidentally, is named Shahrazad, of 1001 Nights fame, a story that the residents of the future Iraq have also forgotten about. (Kahramana is also a name that has a mystical and exotic quality in Arab ears).

“Operation Daniel” by Khalid Kaki (translated by Adam Talib Kuszib) is about an Iraq that has become a province of a Chinese empire. The city in question, Kirkuk, even welcomed this Chinese invasion and its decision to wipe out the past, continuously. All the ancient tongues, including Arabic, are illegal. Only Chinese is allowed. Songs from the past are particularly worrisome and old CDs and tape recordings. Anyone caught singing or speaking in the olden tongues is incinerated and the ash stored-turned into synthetic gems that adorn the boots of officials.

“Kuszib”, probably the goriest and most offensive of the stories, is by Hassan Abdulrazzak. Here we have a future world where most of the human race has been wiped out, hunted down and consumed by an alien invasion. The story tells the tale of a young couple, tentacle wielding aliens, living in what was once Iraq – the soft spot of the globe that the aliens used to conquer the rest of the world. They are having romantic problems and, in the meantime, feast on human flesh turned into delicacies, with blood turned into wine. The Kuszib in question is a hermaphrodite alien who helps the young couple out by feeding them wine and sausages made from a slain human young couple – the sex hormones in the flesh contain passionate memories. (Kus, apparently in Iraqi, means the female gentles while Zib is the male organ. Funny, I thought kus was the f-word in Arabic and the male organ was called a zubr?!)

“The Here and Now Prison” by Jalal Hassan (translated by Max Weiss) is a confusing tale about an Iraqi college boy suffering from some infectious disease that only Iraqis seem to get. He heads off to an Iraqi ghost town with his American sweetheart and they relive the not too glorious past while getting it on for the first time. (What is it with sex and Iraqi authors?)

“Najufa” by Ibrahim Al-Marashi, a university professor in California no less, is one of the more complex of the stories, giving us an upside down world where North American has become a giant desert and home to religious extremism, while the future Iraq has become a haven for tolerance and religious tourism, so to speak. (There’s no oil and morally responsible droids maintain the peace). It tells the tale of a family of Shiite pilgrims heading off to the holy city of Najaf (called Najufa now having merged with Kufa) with the youngest in the brood, Muhammad, trying to relive the memories and experiences of his grandfather Isa. It’s the first time he’s been to Iraq and many of his older relatives haven’t been their themselves. Everyone in this future world speaks a hybrid language and America in particular suffers from an Islamic State-like entity called CAKA (the Christian Assembly of Kansas and Arkansas). For those of you who don’t know, cacka or kakaa is faeces in Arabic, a word even Westerners can relate to, and rightfully so given the resurgence of rightwing racism and xenophobia in the US.

Then again, it could just be the desert environment and the mad scramble for resources. In this future word glucose is controlled by a cartel, not unlike the Seven Sister that dominated the oil industry for so long. It’s always refreshing to see yourself in the mirror of other people’s trials and tribulations, a mirror that science fiction is all about.

Between Satire, Sacrilege and Surrealism

We talked about the ubiquity of history above but another all too common trait in most – thankfully not all – of these stories is profanity and gore. Kaharama gauged out the eye of her soon-to-be husband and specifically after seeing him buggering a young man. There’s a flashback scene in Hassan Blasim’s story where an Islamist militant is naked – he’s covered in hair, making him look like an ape – and has a women shove her finger up his you-know-what. In Mortada Gzar’s story you have a whole snort industry that has taken the place of oil ‘reserves’, and “Kuszib” pretty much speaks for itself.

This is a characteristic of Iraqi literature, I’m sad to say. I was reading an Iraqi novel once – I thought it was an Iranian novel translated into Arabic – and straight away you had vulgar words being thrown around, even before you found out what city the story was happening in!

I would have preferred that this noxious feature of Iraqi literature be used exclusively for domestic consumption and not displayed, like dirty laundry, for the rest of the world to ogle at. Other problems abound. Something that was a bit out of place in Jalal Hasan’s “The Here and Now Prison” was the usage of the example of the lion in the college classroom, noting the difference between a tamed, caged lion and one that is the king of the jungle. In Arabic we have a multitude of names or lion and they all signify different things about the animal. The author could have played around with the name, especially since the original story was in Arabic. The narrative flow of the story was also too speedy, jumping as it were from the classroom to the outside to the ghost town, not allowing you to appreciate just how different this future world was, with the technological and environmental details.

I got the general gist of “Kuszib” since the only of the human races that were able to survive the alien onslaught were the white people, those who ‘collaborated’ with the invaders – an accusation often leveled at Arabs and Iraqis. But the sex scene was way too detailed, bordering on pornography, and the ending was depressing. The young couple, having relived the memories of slain human lovers, feel it is now okay to eat live human fetuses because love is enough. Having them named Ur and Ona didn’t help much either – ‘Ur’ being the first city in Iraqi and world history.

The “Day by Day Mosque” was too abrupt and too in your face. And as visceral as the images were, they didn’t leave lasting images in your head. (Kahramana fared better in that regard, with the border guard at the beginning and end and Kahramana’s tragic transportation, and the so out of place imagery of snow). “Operational Daniel” had potential but the retrospective narration of the story didn’t seem to serve any function since the hero didn’t accomplish anything and may have not intended to.

Still, most of the stories were really good. Four deserve especial mention. “The Corporal” was probably the funniest, exposing how not terribly effective the Iraqi army was thanks to nepotism and classism and party loyalties. I won’t comment on the theology, suffice it to say that I had no idea Iraqi authors were so radical when it came to religious precepts. What happened to the ‘Allahu Akbar’ on the Iraqi flag and traditional religious dress and all those holy sites? The story was still a bit too wedded to gritty realism and surrealism for an SF anthology, if you ask me. (The same goes for “The Worker”, although I did like it. The narrative flow was good, looking at the horrendous world through the eyes of the protagonist, after a brief public announcement intro. The shifting of gears was quite effective and put you into the tragic frame of mind called for here. And the quip at the end about the Americans inspecting Saddam’s mouth to see if he hid a nuclear bomb there was a fitting ending).

The most endearing story was “Najufa”, with stories of families witnessing everything terrible that has happened to Iraq and yet coming out all the better for it, appreciating the good that the past has to offer as embodied through the old recounting their stories while introducing the young to the twilight kind of world that Iraq has always been – with the ultramodern squeezed in side-by-side with the ancient and timeless. It also spoke to our shared humanity, since many of the human characters are only interested in shopping – the Duty Free items at the airport – while others have neuro-implants, allowing them to access the internet and be accessed by it, further disconnecting them from the real world of emotional places and people.

By contrast the droids that police the streets and marshal the pilgrims towards their religious duties actually have a sense of responsibility and pride. It seems there is no such thing as ‘artificial’ intelligence – you either think and feel at the same time, or nothing. And terrorists can be as cold and heartless as machines. There’s lots of Ibrahim Al-Marashi in the story, evidenced by Muhammad’s great grandfather, ‘Ibrahim’, and the prevalence of religious names – Muhammad, Ibrahim (Abraham), Isa (Jesus in Arabic) that also speak to the multiplicity of Iraq’s religious heritage, all embodied in one family. (The ancestry of religions – Judaism, Christianity, Islam, with Abraham as the great grandfather of all can be related to more readily through the generations of the Shiite family in question).

Not that there isn’t a mean streak in the story too. Note that Muhammad has to use his ‘middle finger’ for the passport identity check to get into the country. He made the mistake of using his index finger, like any polite person would. Naughty but subtle enough for my tastes!

The best written, at the level of language and narrative technique, I would say was Hassan Blasim’s story. Flipping into the mind of the suicidal author from the perspective of the modern protagonist, and also moving into the mind of a cat that witnessed the author’s death are high points in the storyline. The poetry, which carries into the English very nicely, is another strong point. The world constructed is innovative too and quite convincing. The construction of this future Iraq also owes a lot to the country’s rich history that the author is no doubt aware of, and to Islamic and Arab motifs. Reference is made to hanging gardens of Babylon in the title, as you can see, and the easy availability of women for a paltry price speaks to depictions of paradise as replete with houris, or palaces full of slave girls.

My personal favorite story, however, was “Baghdad Syndrome”. The sheer romance and tenderness of it and the perseverance of the past, while common themes in many stories, were done to perfection here. (The narrative flow of the story and the poetry are lovely too). There is also the issue of borderline science fiction, with surrealism intruding as it were in many a story, such as “The Worker” and “Kahramana” and “The Day by Day Mosque”. (“The Corporal” doesn’t even rate as SF in my book, as instructive as it is about the past and the future). Not so with Zhraa Alhaboby’s piece. No explanation is given as to how the mutant gene that causes the syndrome can communicate a real-life memory to its sufferers, so you are left wondering if this is a genetic memory or something more supernatural, with the spirits of the dead reaching out to the living through these dreams. It could be either way, but it does not mess up the future world with its robots and takeaway diners and mobile phone apps.

Note that there’s no social media in this story, amazingly enough, probably meant to signify that there is no substitute for proper social bonding and family gathering and human friendships, which are what save the day in the end. (Along with some technology, admittedly, but it’s your emotional and moral predispositions that make you utilize the technology, not the other way round). This is a smart tactic on the part of Zhraa Alhaboby. If you read Philip K. Dick’s forgotten classic Time Out of Joint – a perfect title for many of these stories – you have a 1950s suburban American minus radios!

Nonetheless, the mystery of the strange world that lies behind the scenes and the mundane details of everyday suburban life carry you with the flow of the story and you find yourself accepting this technological lie. The same goes with “Baghdad Syndrome”, although I’d say that most of the SF authors here feel a bit out of synch with hardcore SF. Science fiction is a delicate balancing act between the explicable and inexplicable. Art demands subtly and mystery and not spilling all of your beans too soon in the storyline, whereas science is all about explaining everything – facts, laws, theories – from the word go.

It’s a daunting task and I’m glad to say that Iraq is moving up the learning curve in this regard. But they’ve still got a long way to go.

* Emad El-Din Aysha has a PhD in International Studies, from the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom. But he is also a movie reviewer and literary critic, in his past time, and an aspiring author in the Egyptian Society for Science Fiction.