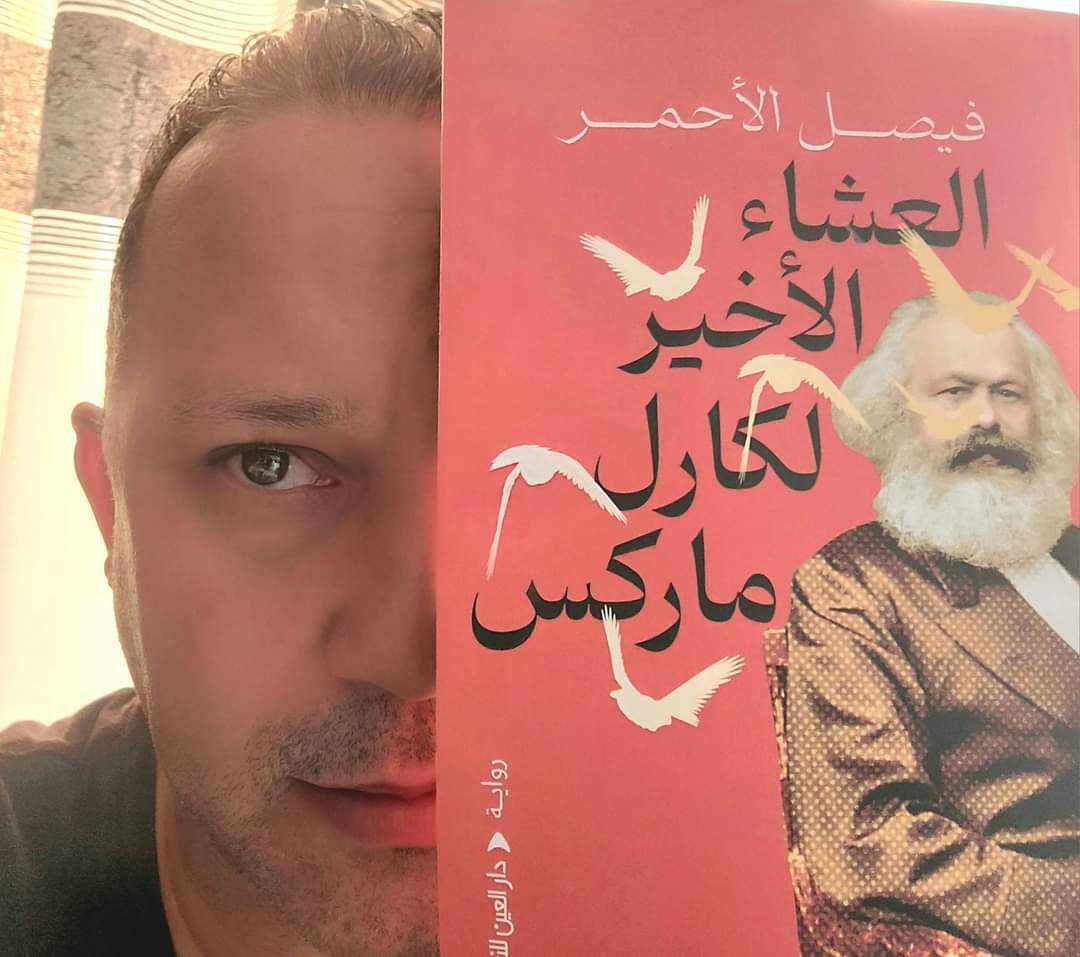

During the Cairo International Book Fair, I made it a point to buy Dr. Faycel Lahmeur’s latest novel, The Last Supper of Karl Marx, even though it wasn’t strictly science fiction. With a little prodding (without naming names), I finally got around to reading it, and what can I say? I won’t say the novel captivated me from page 1—it captivated me from page 2!

By Emad Aysha

You had Karl Marx reminiscing about his life and opinions until then. He talks about the ungodly prospect of going to Algeria for his failing respiratory health and having to rub shoulders with Arabs and Muslims, a failed race of people in his bloated opinion.

Marx was notoriously prejudiced against the poor and wretched of the earth, such as Eastern and Southern Europeans. But there’s no harm in imagining him learning the error of his ways as a guide to future generations. If he can get himself out of his clash of civilizations mode of thinking, there’s hope for the rest of the West!

I can’t speak for Marx, the man in this story. To my knowledge, he was not a loyal and devoted husband. Still, one of the most endearing qualities of this formidable novel is seeing Marx as a diehard romantic, spending most of his solitude reading his wife’s diary. She was such a formidable, gentle, devoted woman who was – unlike her husband – reconciled with herself.

She was a good Protestant and all for liberating the masses from the tyranny of capital and the church, and by the end of the novel, when Marx has his Christ-like last supper with the imperialist bigwigs in Algeria, he seems to find himself along that reconciled path. You feel almost that Marx is speaking life as a Sufi, with lovely spiritual poetry spewing from his lips despite his most cynical efforts to be a materialist.

Marx also learns to live up to his cosmopolitan credentials here. He talks about being a permanent migrant with nowhere to go back to and being glad for that, provided he’s got the right woman to live for and see as his home away from home. While at his hotel, he stumbles on a young Algerian couple, getting romantic amid a treasure trove of books and manuscripts in multiple languages.

It’s an illicit stockpile for the ‘foundationalists,’ Algerian schoolteachers, labor leaders and Utopian thinkers who desperately tried to modernize and mobilize Algerians to non-violent protest. But more important, they started as a secret society dedicated to protecting the memory of Algerians from being erased, collecting land deeds (from the Ottoman archives) that the French authorities claim don’t exist.

What a striking parallel between Palestine and the Israeli erasure of our past, whether it be private land holdings, tribal lands, or religious endowments set up specifically to stop people from selling their land to foreigners.

This interlude in the novel, which is just over 190 pages long, came at the right pacing point. If the diary reading had gone on any longer, the story would have become too indulgent. And you can tell the hotel is meant to be Algeria, presided over by foreigners but still true to itself.

The girl he intercedes not coincidentally gives him a local cure for his lungs, a mixture of natural honey and herbs and spices, and it works wonders. In a nice humorous aside, Marx insists on finishing the bottle of honey because, if you leave honey for too long, it turns sour.

By the end of the novel, he regrets having to leave while not cured. He’s not better off but not worse off either, and the sunlight has done him some good, too, allowing him to move around with more energy.

His only regret is that he wasn’t able to do more for the miserable working Algerians, having learned just how hypocritical the West is – with de Tocqueville blabbering about democracy for all while embracing the ruthless occupation of Algeria.

Marx is also a spokesperson for local problems in the novel, such as liberating religion from being weaponized by the state while respecting people’s transcendent needs. In the closing scene, another character talks about the happiness driving the miserable profession of the writer and how the Algerians will not write until this westernization phase finally blows over and they recapture their civilization.

It’s like wanting to wake up from a bad dream. Well, it is about time that an Arab or Muslim author staked his claim to such a key figure in Western history, proving once and for all that our opinions on the world's struggles and the exploits of another civilization are valid and valuable.

But the key is to do it all in a fun, eloquent, and distinctly Arabic way. This is a modern novel in every sense of the word but also an Arab-style parable. It does not focus on a beginning, middle, and end with an inciting incident, climax, and resolution. Instead, you get a quiet transformation happening in the so-called protagonist that he himself may not even be aware of.

Cultural appropriation in reverse is pointless if it’s tedious, verbose, or nothing more than a cheap imitation of Western literary norms. That does not happen here. Marx is made to talk like a Sufi saint who harnesses the revolutionary potential of religion but in a plausible way and in his complex philosophical terms.

From erosion to evolution, you could call it. And it’s so endearing it's delightful, with a mirror raised to the West, which we, as Arabs, can see our true and twisted selves in it too.

This puts Dr. Faycel Lahmeur on the same existential plane as Philip K. Dick. The literary sun of the Arabs now rises in our West!

My guess is somebody paid you to write this article? Otherwise, I don’t think you would have spent your time reading it much less reviewing it.

💜 Angel NicGillicuddy