The Levant News Exclusive - By Emad El-Din Aysha |

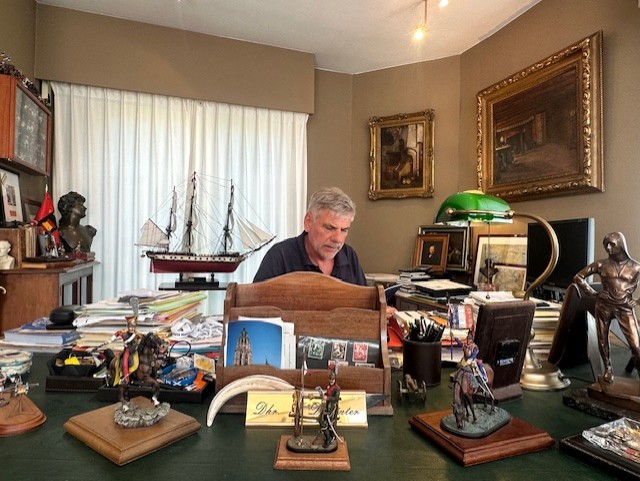

Mark Sedgwick is Professor of Arab and Islamic Studies at Aarhus University, and Chair of the Nordic Society for Middle Eastern Studies. He studied history at Oxford University, did his PhD at the University of Bergen, and taught for many years at the American University in Cairo before moving to Denmark.

Reading Mark Sedgwick, like knowing him, is a treat. (We met when I was teaching at the AUC myself). He’s about as rigorously academic as you can get but communicates his compendious research in language that is clear and straight to the point, for the specialist and the layperson alike. Nothing could be more pertinent nowadays with all the miscomprehensions about Islam in the West. He’s done a great deal to pick apart catchall phrases like radicalism and terrorism and fundamentalism that are meant to mislead. The same goes for us. If you want to see how inadequate labels like ‘the West’ and ‘Occidental’ are, please read his classic Against the Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004; paperback 2009). The so-called Orient has always been essential for the West to hold up a mirror to itself, questioning its own beliefs and methods, challenging itself to better itself.

Anyone who thinks there is no way to go except the modern way of the West, should read this book. Anyone who thinks the West is all one thing and by necessity antithetical to Islam, should read this book, and all of Mark Sedgwick’s books for that matter. Seems we have a hole in our understanding of Sufism too, all the more reason to read this interview!

Emad El-Din Aysha: Dear Dr. Mark Sedgwick. Just let me begin by saying it’s an honour to have someone of your intellectual caliber here with us in The Levant. An overview of your personal and academic background is called for. Where did you grow up and what drew you to studying Islam specifically?

Thank you, and great to be with you. I grew up initially in London, and then in Spain and France, as my parents moved around Europe. I was first interested in history, which is what I studied for my first degree. I grew interested in Islam only after moving to Egypt in 1987. That move happened because I visited a friend in Cairo, liked it, and thought it might be an interesting place to spend a couple of years… Which then extended to two decades.

EEA: Do you come from a long line of British Orientalists?

Not in terms of my family. My father was a businessman. But after my PhD supervisor died earlier this year, I thought I’d look at that line—at who his supervisor had been, and who had supervised him, and so on. To my slight surprise, I found that the line of scholars to which I belong went back not to seventeenth-century Oxford, but to Sayyid Ahmad Khan, the Indian reformer who grew up at the Mughal court, founded the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College, and died in 1898. Ahmad Khan had mentored Thomas Walker Arnold, the first Western scholar in the line that ended with my own supervisor. I also found that all of the Orientalists in the line save one had taught in the Muslim world for some part of their careers; the one exception, H. A. R. Gibb, was born in Alexandria.

EEA: Since Edward Said the ‘objectivity’ of the Orientalist has always been in question. Fortunately, you’ve taught in Egypt at the American University in Cairo, where we first met. Would you say that living in a Muslim country and interacting with Arabs and Muslims on a daily basis gives you an entirely different perspective on your subject matter?

Indeed. Said’s point was partly about individual Orientalists, but more about the system in which they lived and worked and which moulded their work. The American University in Cairo was a very important influence on my own formation, and certainly gave me a different perspective. Ironically, the American University in Cairo was originally a product of precisely the unequal power relations that Said drew attention to. But the American University in Cairo is much more than its origins—in many ways, the “in Cairo” is now more important than the “American.” Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that there are three influences at work: the American, the Egyptian, and the hybrid. I think I became quite hybrid myself in the end, and found that many Egyptians are quite hybrid too. Hybridity is fatal to the binary perspective that is central to Said’s model of Orientalism. A lot of that model was about the construction of the “Other.” I am not sure who the “Other” is from the perspective of AUC… It is certainly not Arabs or Muslims… Ahmad Khan’s Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College, of course, was another example of hybridity.

EEA: You have several books on Sufism, the most recent of which include Western Sufism: From the Abbasids to the New Age (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016) and Global Sufism: Boundaries, Structures, and Politics (with Francesco Piraino; London: Hurst, 2019).

One of the hardest things about studying Sufism is defining it. Why is this such a difficult task and how do you define Sufism?

My own approach to defining Sufism has changed recently. I used to take a sociological approach, focusing on the tariqa as a community and on the role of the shaykh. But then I realized that tariqa-Sufism is just one form that Sufism has taken, and that although it was the dominant form in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it has not always been the dominant form. And is not the only form today. So now I tend to see Sufism in terms partly of practices, and partly in terms of theory. Sufism is what is called tasawwuf in Arabic and many other Muslim languages, and tasawwuf is also used to translate the European term mysticism. Defining mysticism is even more difficult than defining Sufism, but my favorite definition focuses on particular understandings of the relationship between the soul (ruh) and God, understandings also found in classic Arabic philosophy. Most Sufis are not philosophers, of course, but Sufism is marked by philosophy.

EEA: How influential has Sufism been in European history, intellectually and culturally? What’s the secret of its appeal?

It was precisely the philosophical ideas that are associated with Sufism that first interested Europeans. Texts were the first aspect of Sufism that they encountered; Sufism as lived reality was not really accessible until travel between Europe and the Muslim world became easy. And what texts contained was, of course, ideas. One of the most influential texts was Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān by Abū Bakr ibn Ṭufayl, written in the twelfth century, and translated into Latin, and then into other European languages, in the seventeenth century. What Ibn Ṭufayl had written was a defense of Sufi philosophy and practice; Europeans read it in the context of their own, somewhat different, concerns. This was the earliest significant contribution of Sufism to European intellectual history. For cultural history, one has to wait until the nineteenth century, and here the major event was the publication of Goethe’s West-östlicher Diwan (West-Eastern Divan) in 1819. As the title suggests, this was inspired by Persian poetic models, and Persian poetry and Sufism have always been intertwined. Goethe was not a Sufi, however—he, too, had his own concerns.

EEA: Is Sufism one of the few instances when Islam is perceived positively in European history?

Today, yes. In the nineteenth century, Sufism was synonymous with fanaticism, and would have been identified with terrorism, had the concept then been current. This was because most of the anti-colonial resistance movements of the time drew, in one way or another, on Sufism—organizationally, not in terms of philosophy! That was all forgotten, however, in the period after the First World War, when Europe was trying to recover from its own experience of extreme violence. People became more and more interested in all sorts of alternatives, including religious alternatives. Sufism came to be seen very positively, understood primarily in terms of its philosophy and its poetry. This continued until the Sufi poet Rumi became one of the best-selling poets in America, as he remains today.

EEA: That being said, should we as Arabs and Muslims be ‘worried’ about this popularity, especially in Western political circles? Do you know of any instances where Sufism is inadvertently serving a political agenda pushed by Western states?

There is no real problem in Americans reading Rumi. Some understand his poetry rather superficially, but a love of Rumi at any level is hard to combine with Islamophobia. Others dig deeper, learn more, and in some cases even end up converting to Islam. In Western political circles, however, there are some who see Sufism as a “moderate Islam” that should be encouraged in the fight against “extremism.” This view is evidently shared by some in the Arab world, explicitly in the case of the Moroccan king, implicitly elsewhere. This puts leading Sufis—writers, speakers, shaykhs of tariqas—in a difficult position. Should one accept politically motivated support? Money is always useful if one has a message to spread; freedom from restrictions is always useful in a country where non-state activities may be restricted. But there is a price to be paid: the hand that feeds one may become so visible that it discredits one. This, I think, is the greatest danger for Sufis. I don’t know of any cases of a Sufi doing or saying anything that really damaged the interests of the Muslims or the Arabs, but I do know of Sufis who even I think are a bit too close to political leaders who I do not much like.

EEA: Not too long ago we at The Levant conducted an interview of Dawoud Kringle, an American musician who’d converted to Islam. He even wrote a Sufi-inspired science fiction novel, A Quantum Hijra (2011). Does it surprise you in any way that such an alien and high-tech genre as SF can be open to the influence of Sufism?

I didn’t know of A Quantum Hijra and I look forward to reading it. I wonder how it will compare with G. Willow Wilson’s Alif the Unseen, an amazing novel, also written by a convert to Islam, which has no Sufis, but takes us into the world of the jinn… I’m not sure that SF has to be high-tech, actually. It may be high-tech, but it can also just move into alien or alternative realities without much reference to any sort of tech. Alif the Unseen is almost SF in some ways. The Sufi understandings of the relationship between the soul and God that I referred to earlier are also understandings of reality, and thus of alternative realities. Sufi poetry has always explored alternative realities, in fact. SF and Sufism actually fit quite well.

EEA: Would you encourage more SF writers to experiment with Sufi themes and techniques in their literature?

We ask because this seems to be sorely lacking in this part of the world, and Arabic science fiction isn’t popular enough as it is.

Arabic science fiction may not be very popular, but Sufi fiction sometimes is—I am thinking here of The Forty Rules of Love by Elif Shafak, which did very well in Arabic translation. Yes, I think I would encourage more SF writers to experiment with Sufi themes. I would certainly like to read more Sufi-inspired SF myself.

EEA: Finally, what is the best way to counter attempts to misrepresent Muslims in the international media and Western popular culture? Apart from interviewing you and Dawoud Kringle, that is!

I’m not sure much can be done about the international media and Western popular culture. Sufism has been seen positively in Western alternative culture, and perhaps in elite culture. It never really got anywhere in popular culture. So I don’t think Sufism will help there. One of the things that has really struck me since I left Egypt and moved to Europe is how many Westerners manage to combine strong views about Islam and Muslims, which are never positive, not just with very little knowledge about them, but with very little interest in becoming more knowledgeable. Perhaps what we need is more Islam-themed SF… Frank Herbert’s Dune certainly got through to Western popular culture. The trouble is that most readers of Dune do not realize that the sacred text of Herbert’s Fremen is actually the Quran.

Very interesting indeed

Very interesting indeed and insightful and vibrant understamding about such kind of academi arena

[…] see this in everybody from Sayyed Hossain Nasr to Ali Shariate – the book to reference here is Mark Sedgwick’s Against the Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth […]