By Emad El-Din Aysha, PhD

وَإِذْ يَمْكُرُ بِكَ الَّذِينَ كَفَرُوا لِيُثْبِتُوكَ أَوْ يَقْتُلُوكَ أَوْ يُخْرِجُوكَ ۚ وَيَمْكُرُونَ وَيَمْكُرُ اللَّهُ ۖ وَاللَّهُ خَيْرُ الْمَاكِرِينَ

And [remember, O Muhammad], when those who disbelieved plotted against you to restrain you or kill you or evict you [from Makkah]. But they plan, and Allah plans. And Allah is the best of planners.

--- Quran, Surah Al-Anfal, Verse 30

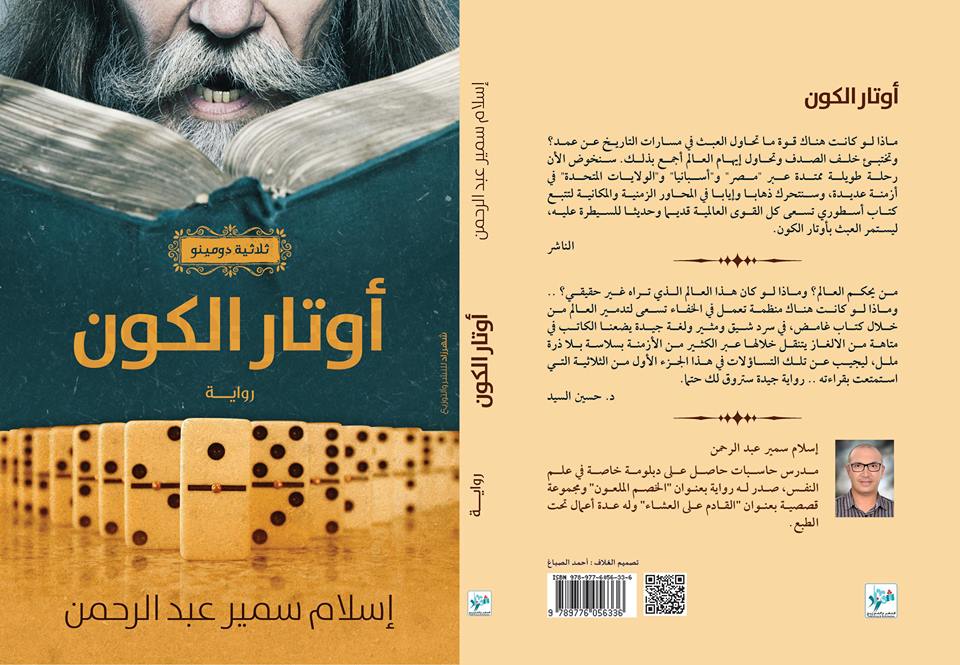

This interview took place on 28th February 2019 with the author of sci-fi conspiracy thriller ‘The Strings of the Universe’ (أوتار الكون), Eslam Abdel-Rahman (إسلام سمير عبد الرجمن). He was the guest of honour at the sci-fi lecture of the Abd Al-Qadir Al-Husseini Institute (ندوة الخيال العلمي بمؤسسة عبد القادر الحسيني الأدبية). This interview took place before and after the event, with some follow-up questions afterwards.

Also present at the event, introducing Mr. Eslam and reviewing the novel were Muhammad Naguib Matter – an engineer, author, active member of the Egyptian Society for Science Fiction and the man in charge of SF at the institute and an– and noted literary critic Nadia Kilani and author Rania Masoud. Another literary critic, Mr Khaled Gouda Ahmed, as well as author Ahmed Salah Al-Mahdi were meant to be on the panel too but through some unfortunate circumstances were not able to make. (Both are members of the Egyptian Society for Science Fiction). The audience to the event was no less eventful with the presence of three young novelists, Mahmoud Abd Al-Aal, Kirolous Atef and Muhammad Muhi Al-Din, friends of Mr Eslam himself. (Not to forget that I was in the audience too, by an authr and member the Egyptian Society for Science Fiction as well).

The novel, for those who don’t know, is part of a trilogy. The ‘domino’ trilogy, about a secret society called the Orchestrate that tries to influence the direction of history by manipulating so-called accidents. They can see future paths and pick the one that suits them. This first instalment of the trilogy is told through multiple narrative tracks, skipping from ne time period to another, back and forth, and from one location to another. Some mysterious individuals are hot on the tail of an Egyptian by the name of Mahfouz Zidan who has give them the slip, holding in his possession a priceless manuscript that can change everything. Mahfouz used to work for this secret organisation, and was recruited and trained specifically by the man who is trying to track him down. Mahfouz is a chess master but, just as importantly, a historian, and they; hired him in part to put his historical skills to good use and track down that manuscript, penned by a Muslim scholar from Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain) named Al-Hassan Bin Abbad (الحسن بن عباد), who was the first to learn the secrets of predicting the future. We’re introduced to this historical figure, in person, along with episodes where we tragically witness the decline and fall of Islamic Spain and with that the attempts of the Vatican to acquire the manuscript, during the Spanish Inquisition. (The ultimately fail but the secrets they are able to acquire end up in the hands of Nostradamus!)

The novel is very nicely written, engrossing, exciting and innovative and so a refreshing change from most of what is written in Egypt nowadays, whether pulp fiction or so-called high art. But that’s not the half of it. The event Eslam spoke at is worth talking about on its own, and for much the same reason as the novel. That is, everything was working ‘against’ it, cosmic forces beyond our control.

There was the train cash the day before that threatened to prevent Eslam to get here, by train from Alexandria. There was the stormy weather, which almost put me off going. There was my friend, one of the panelists, Ahmed Al-Mahdi, who couldn’t make it. (We were going to go together since I frequently forget how to get there). There was work that day, and the slow, slow traffic heading back from work. (I also took the wrong bus, thinking it was faster. It wasn’t). And there was also an altercation outside the metro station of Helmiyat Al-Zaitun. Not with a person, but a dog. Almost got bitten and spent most of the rest of the day going to pharmacies and hospitals to find someone, anyone, willing to check my leg to see if I’d been bitten and needed treatment.

Lucky, everything turned out well in the end and even the panel finished on time and we all had a lot of fun.

It was like it was ‘meant’ to happen!

Emad El-Din Aysha: First of all, please introduce yourself and introduce your publications? What genres do you write in and what attracts you to science fiction?

Eslam Samir Abdel-Rahman: My name is Eslam Samir Abdel-Rahman. I’m from Alexandria. Born 1973. I’m a school teacher, computers, and have degrees in data systems such as Access and Oracle.

I’m married and have a family and I’ve only been writing professionally for a few years now but I’ve been writing since I was a child, in notebooks, which I still have and cherish. It drove my parents crazy and they regretted the day they got me books and comics to read, but I worked out well in the end.

Genres, mainly horror and fantasy horror. (I have a diploma in psychology too. That helped me a lot with phobias and the nature of fear). My attraction to science fiction is how rich it is and also how it is constantly renewing itself. A tireless genre, reinventing itself.

EEA: Now to talk about your stunning novel. The hero, Mahfouz Zidan, has a son named (بيجان). Can you explain this choice of name?

ESA: No particular reason. It’s a name I inherited from my childhood. I’d written stories, as a kid, with a hero by that name, so it just stuck with me.

The same goes for the hero. There’s nothing special or symbolic about the names. He’s a chess master and brags out load that he can beat this opponent and that opponent in so many moves. I was a chess player as a kid, in love with it, and I had a friend who was exactly like that. And he always defeated me in the set number of moves, as hard as I tried not to lose.

I turned that, afterwards, into a talent, indicative of an ability to see future lines, which is why the Orchestra is interested in him. Recruits him, with similarly talented characters, one a stock broker, another a gambler. All games of reasoned chance.

EEA: Mahfouz Zidan, or Hajj Mansour as he calls himself in hiding. He’s an Egyptian. Are you hinting that Egypt, as the centre of the Arab world, is responsible for preserving our heritage as Arabs and Muslims?

ESA: I’m an Egyptian, and from Alexandria, so its natural for me to have an Egyptian hero and an Egyptian setting. Nothing specifically symbolic about it. It’s just what I want to write about it, appeals to me. Not to mention that I made it out that Nostradamous was able to learn to predict the future based on our insights as Arabs!

Again, our condition as Arabs and Egyptians is what interests me. And I definitely do believe that we have to cherish and preserve the past. There are books, stacks of books, in the Vatican vault containing God knows what secrets from the past. Look at the heritage we lost in the great library of Baghdad, Dar al-Hikma, that the Mongols threw into the river, in their arrogance and ignorance. There are bound to be secret collection of books all over the world that could change the face of life on our planet if they were ever known and studied by the public. The books from the Library of Alexandria and the books of Ibn Rushd that were burnt, etc. I played on this angle in my novel.

EEA: The fictional character responsible for discovering how to manipulate the flow of events, Al-Hassan bin Abbad. Why does he disappear after winning a decisive battle for the Muslims in Al-Andalus?

ESA: You’ll have to wait for the third novel to find that out!

Don’t want to spoil it for you.

EEA: What prompted your story? Where did you get the idea from? And why a trilogy?

ESA: A book I’d come across, a famous book in Arabic, I’m sure you can find it online in pdf form, about the role of chance and stupidity in human history. I paraphrase portions of the book in the novel itself, through the mouthpiece of Arthur Willington, the historian who almost figures out what the Orchestra is up to, and pays the price with his life.

This history book, by Erik Durschmied, It just got me thinking and reading history and wondering if all these coincidences that ended up serving a specific direction in history were only coincidences, such as the bomb that almost killed Hitler failing to do this because they found it improper to have a suitcase close to him, and the wood the table was made of was especially thick, as if somebody had chosen it for that purpose.

As you can guess, I love history. I don’t read it in a scholarly, academic way, with all the terminology. But I love to read it. I can read an entire encyclopaedia just to produce out of it one short story. My friends always balk at this, but its’ well worth the effort. To distil that wisdom with all its lessons for us.

Though I do skim a lot when reading history and focus on what I’m looking for. I do have a job and a wife and three children to take care of.

And here’s a funny coincidence. I’d come up with Al-Hassan bin Abbad, before I’d read the history. Then I asked a historian friend of mine about his name, said it sounds familiar. Then he told me about Al-Mutamid bin Abbad.

This created the connection between him, this completely made up character, and the great Muslim commander and leader Al-Mutamid bin Abbad at the battle of Zalaqa in Andalus. I then transformed Hassan into the black sheep of the family, someone frowned upon for being a scholar and mystic and someone who wastes his time looking up at the stars and doing experiments in alchemy, instead of a warrior politician like his brother and the rest of his clan. That’s why he is promptly forgotten in the history books. And it worked!

The same goes for dates. When I choose a date, a year for an event or to present a character. I can often choose it at random. But when I read on the date in history and discover something interesting happened, I incorporate that into the story. But you have to research also to make sure you didn’t make any historical errors. That’s another game of chance that can actually help you write, force you to create connections and repair a storyline.

The same happened with my horror-fantasy novel, a Sufi mystery thriller called Abu Karamat: The Accursed Inheritance. I talk about the Nagei Hamadi texts in it, but add a little material of my own, of course. But while writing and researching, and asking colleagues who are experts, I found a mistake I made, concerning when something happened, so I found a way of fixing it. instead of the hero finding a text his grandfather wrote 40 years ago in his grandfather’s study, I have someone else adding this text, since it hadn’t been written at the time of grandfather as I’d initially thought.

Chance plays as much a role in writing as it does in life.

As for my trilogy, this also came through an accident. I’d originally conceived of the story in serial form, nothing more. I wasn’t that ambitious to be honest and I’m more of a horror and fantasy writer. What happened was that I’d given it to a friend who loved it and he gave it to a publisher, recommending it enthusiastically. Ahmed Khaled Tawfik was supposed to endorse it!

Then the publisher (without naming names) just ignored it till I got fed up of waiting and turned it into a novel instead, a trilogy of novels.

EEA: Have you read Philip K. Dick or watched the movie Adjustment Bureau (2011), by any chance? It’s more fantasy than SF, but you have these agents helping direct the future and stopping mankind destroying itself.

ESA: I’m afraid not. I read a lot of science fiction growing up, but mostly Arabic or translated into Arabic. Nabil Farouk and Ahmed Khalid Tawfik, and Raof Wasfi, mainly. Tawfik Al-Hakim and Nihad Sharif and Mustafa Mahmoud as well. Nihad Sharif in particular had a very fertile imagination, really weird and colourful. And also some Ray Bradbury and Isaac Asimov, in translation.

EEA: Ah, in that case, have you read Asimov’s Foundation saga? There’s the science of psycho-history, which tries to predict the future, the future history of mankind, using mathematics.

ESA: No, I’m afraid I haven’t read these novels. I think they are one of Asimov’s great works that haven’t been translated into Arabic yet.

EEA: What about Dan Brown of Da Vinci Code fame?

ESA: Ah, Dan Brown I have read and am a big fan. He’s a tremendous thriller writer. But I try to give my similar concerns a distinctively Egyptian flavour and Arabic flavour. Hence, the Egyptian hero, in hiding in and in a very Egyptian neighbourhood, with the poor and the qahwas (coffee shops).

I am influenced by him but also by Ahmed Khalid Tawfik, and the great Egyptian author explained that writing, the mind of the author, is like a blender. Lots of different ingredients go into it and mix to produce a final original work.

EEA: Do you see Alexandria being like Al-Andalus, a very cultured, diverse and urbane place?

ESA: Alexandria is a great city. Exquisitely beautiful and full of welcoming people, a result of how small it is, compared to a giant city like Cairo.

Alas, I never drew a connection between it and Al-Andalus. But, now that you mention it, we can also draw a comparison between Alexandria and Al-Andalus. Both carried the flame of a great heritage of civilisation and cultural accomplishments.

And my choice of Al-Andalus was not coincidental, of course. I am very, very fondly attached this period of history. I have read a great deal in its history, and mention it in my third novel in the trilogy, in the penultimate phase. A paradise on earth that we squandered as Arabs, as always. You can see this in Ahmed Khaled Tawfik’s novel Shabeeb, where the Americans create a country for us, the Arabs, and it’s at first a Utopia, then we ruin it as we did with Andalus. The bad things, corrupt things, come out of us.

There’s so much to learn from Al-Andalus, in a good way. The civility and urbanity and intellectual life and scientific accomplishments and the tolerance.

EEA: Why is the Vietnam War mentioned?

ESA: Because it happened. Because it changed everything. America was never the same again. A whole generation of Americans were never the same again. It had to be dealt with.

EEA: Do you see any connection between Vietnam and what’s happening now in our region, with the Americans in Iraq?

ESA: Definitely! It’s all to do with empire. The same arrogance, the same greed. The same insistence on changing everything through overwhelming power. The only difference is that in Vietnam the Americans were defeated. Decisively defeated in a way that will humiliate them, for ever.

EEA: You mention Nixon’s destruction of Hanoi by a massive assault of B-52 bombers, based on advice given to him by a foreign policy think tank, which turns out to be a front for the Orchestra. Would you say that America went into Iraq, in part, to compensate for their loss in Vietnam?

ESA: Not ‘really’. I hadn’t actually stopped to think about it!

EEA: Oh, have you watched Rahim, the Egyptian TV series. They explain there, and it’s quite thrilling, that money laundering was a big part of the Iraq War, turning all that oil money into fictional companies and money transfers. In that case, is ‘globalisation’ a topic in your novel as well?

ESA: I didn’t have globalisation specifically on my mind as I wrote.

EEA: Your character Arthur Willington also says explains that these accidental events being controlled by the Orchestra are not meant to maintain world peace and human advancement, but further American imperialism.

Is seems that you see history, the control of secrets from the past, as the key to global domination?

ESA: Naturally I believe that controlling events can push history in a certain direction and create hegemony for a single state, a world power.

If you remember the scene with Arthur Wellington, in his castle, he had a giant map with pins and strings between those points, coloured string, to show how history could have gone, was meant to go, and the way it actually developed thanks to the deliberations of a secret hand, creating accidents.

If it hadn’t been for such an accident, the Boston Tea party, there wouldn’t have been anything called the United States to begin with!

EEA: After reading your novel, Mr Naguib came out with the distinct impression that the world was under somebody’s control, and that it was the Americans pulling the strings. (That’s a paranoia we all suffer from in the Arab world). Was that your intention?

ESA: I was hinting at the Masons in the novel. The Orchestrate is an extension or derivative of them. And don’t forget that Gorge Washington and the very first American presidents were Masons. For them, there had to be something like, some entity like the United States.

It will become clearer in the second novel, when Mahfouz meets his American teacher, the man who recruited him. I can’t tell you exactly what happens her, but he explains why they had to create the US, and maintain its supremacy. In service of mankind, as they see it.

But look at it this way. Why did this organisation insist on saving Hitler’s life? Because if he’d died as planned in that bomb plot, then the war would have ended immediately, and the Americans wouldn’t have been able to take over. No Normandy invasion and occupation of Berlin, and no Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And France and Britain would have kept their empires and been as powerful as after World War I.

EEA: How much research did you do for the book, particularly on Watergate and Vietnam? (You give very detailed and plausible accounts).

ESA: A great deal. Watergate especially interested me because a single piece of tape, found by the security guard at the Watergate building that day, a freak event, brought down an entire government. Imagine that.

That’s chance for you. And the truth is that even that security guard hesitated to report it and call the police. What I did in my novel is that the Orchestra deliberately causes a series of interrelated accidents that prevent the original security guard from being there, someone who isn’t terribly bright or diligent in his work, to be replaced with the security guard who actually did his job right.

And in real life he almost didn’t do it right!

EEA: Were you afraid that the reader wouldn’t be interested in these historical references to Vietnam, Watergate and also the Second World War?

ESA: No!

The success my novel has enjoyed, with the second instalment coming out shortly, has put the lie to such claims.

Things are changing and fast. Horror, and now science fiction, has never been so popular in Egypt. People are bored of realism. I certainly am. I could never stand to read societal novels as a kid. I’ve only read a little Naguib Mahfouz, Yousef al-Sibai and Yousef Idris, but only when I decided to become a writer and work on novels, to prepare myself. But I found I cannot read social fiction!

I did read Naguib Mahfouz’s historical novels before though, and like those.

Again, we have to thank Nabil Farouk and Ahmed Khaled Tawfik, and Raof Wasfi, for this. They raised an entire generation with an unquestionable thirst for SF, fantasy and horror, and also thrillers. There are lots of people out there who are hungry for mysteries. Ahmed Khaled Tawfik deserves special mention. Not just as a fantastical author but just as an author, such a gifted writer, with beautiful and memorable prose. And a great sense of humour. Very Egyptian sense of humour.

You always come out with language lessons reading him and compact scenes with very vivid images in your head.

EEA: It’s very good that you’re not into mainstream realist literature, otherwise you would have just imitated them in your own writing. You wrote this novel in a very innovative way, certainly by Arabic standards. You leap from past to present, with a multitude of characters in different places. This is a very ‘panoramic’ narrative format. Did you do that on purpose?

ESA: Believe it or not, no. I don’t have the time. My job and my family life take up all my time for me to have the luxury of looking into literary theory. But, I will tell you this. I was attending a panel discussion once, a literary event about my novel, and I found a distinguished professor, Dr. Ihab Badawi… no, Ihab Bedaewi, presenting a paper on my novel and said it was an example of the ‘post-modernist’ novel. Imagine that, my unintentional style of writing. And his paper was ten pages long, and I used to make fun of this term, post-modern.

I don’t have the traditional beginning, middle and end format that we as Arabs are so fond of writing in, I assume from imitating classical literature from the West. You know what, you are right, thank heavens. Didn’t read enough mainstream literature, and foreign literature too!

EEA: Have you lived abroad or travel much?

ESA: No, I’m an Alexandrian at heart. I’ve only ever come to Cairo to promote my books or to help friends. And I’ve been outside the country on one occasion, umra [lesser pilgrimage] to Saudi Arabia.

EEA: How important is religion to your novels?

ESA: Quite important. I have a strong Sufi streak in me, as I mentioned in relation to my novel Abu Karamat. I also did a horror series called Demon Hunter. I invented a whole Sufi order in it, the Tariqah Al-Sirdariyah. The hero is descended from a Wali, a great Sufi Sheikh.

I’m not a member of a Sufi order or an expert in the field, and to be honest I’m not always attracted by dervishes and dances. But spiritualism is essential to me. To me Sufism is about patience. Patience with all the terrible things that can and often do happen to you in life. Its about humility. It’s about learning to keep calm and judge things calmly, looking at the problems of society, studying them, and raising above through the relationship with God.

This is what I explored in my novel Abu Karamat. The hero is a police officer, fighting terrorism, and he endures a terribly tragedy in his life. A double tragedy. His wife dies in childbirth and, at the same time, he guns down someone he thinks is a terrorist someone with his face covered. When he sees the identity of the terrorist, it turns out to be a boy.

It devastates him and he quits the job and leaves the city entirely, so he heads to a village in southern Egypt where his grandfather served once. That’s when he discovers his grandfather was a Sufi sheikh and is buried there, even though he was a cop. He learns about the legends surrounding the burial plot and the mysterious house of his grandfather, with secrets hidden there, and the strange things that happened when they tried to remove his grandfather’s grave. Back to his ancestor’s house in southern Egypt, where he learns about his grandfather, a Sufi mystic with a special burial plot that has hidden charms.

I published the novel at this latest Cairo book fair, and I’m very proud. A great deal of work went into researching and writing it.

EEA: Could this help create new genres in Arabic literature? Sufi fantasy or Sufi science fiction even? There is, in fact, Sufi science fiction, in the West!

ESA: I would say yes. Imagine a story, a scenario from Western SF, where you have someone at a Buddhist monastery, learning and training and gaining enlightenment, and through this he attains superpowers, becomes a superhero.

We can do the same, there is no reason why we can’t do the same, with a Sufi. Someone praying and reading and living in a mosque, dedicating himself to the service of God. That’s part of the thematics of Abu Karamat, with karamat (blessings), these magical powers certain Enlightened people in Muslim history gained. Like walking on water and flying through the air, or so they say. This is a controversy around this. There are Hadiths about this and some examples from the Companions of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). But, the point is, we can use it for writing and compete with others in our own way.

I happened to think only certain unique people can attain these powers, by virtue of religion, but in fiction you can explore this and make it part of a storyline, a theme, a dramatic beginning. It is a game and you can get away from such real-world restrictions.

EEA: Returning to science fiction, Mr. Naguib says that your novel أوتار الكون, is a reference, or could be a reference to superstring theory, the word in Arabic is the same, أوتار. I thought this too. Care to comment?

ESA: No, unfortunately I wrote the novel without this in my mind, superstring theory as outlined in the physis textbook.

That being said, I did talk about the theory of connectedness in the universe and how parts of the cosmos function together to form a symphony, a beautiful and comforting totality that only the select few within the secret organisation of the Orchestra can feel as well as see. They are the conductors of this symphony, meaning there is an innate balance between the forces of evil and the forces of good.

Like the balance between Yin and Ying. The composers have to maintain this balance between good and bad or else they will ‘hear’ something askew and so they will know that something needs fixing.

EEA: You never cease to amaze. Best end the interview at this point or we will be here all day.

ESA: Good bye and God bless!

Oh, a final comment. I don’t want anyone to come out of this with the impression that I’m a fatalist or anything.

I was able to make it to the lecture, and back in one piece, despite everything that happened. My leg turned out to be fine, and Eslam himself didn’t get held up on the way to Cairo and to the event, and he’s still in touch with me since getting back to Alexandria.

There’s such a thing as ‘determination’. Not stubbornness, mind you. A combination of will power and preparation, such as leaving early for an event just in case there’s traffic, and asking directions from several people to be on the safe side, and finding alternative means of transportation. That’s what Eslam did, as did I, and it panned out in the end.

Chance plays a role in history, and writing, no doubt. What Machiavelli called Fortuna. But so does determination, what Machiavelli called Virtù or ‘virtue’. No matter how much fortune (chance) gets out of hand, Virtue, if implemented properly and for long enough, will win out in the end. So we shouldn’t use the conspiracies directed at us as an excuse to do nothing – Nadia Kilani pointed that out in her commentary.

Vietnam, again, is perfect example. I eriously doubt the Americans or some secret imperialist cabal got the country into that war deliberately to lose it. (In the novel the Orchestrate use their machinations to get rid of Nixon specifically because he is losing the war, a war he shouldn’t have entered into to begin with). I can ad that the B-52 strike against Hanoi only worked after repeated failures, with a threatened mutiny from the airforce crews. I found this out watching an American documentary series about the war, and while watching it you discovered why the Iraqis hadn’t a chance in hell in warding off the Americans either in the Gulf War or Iraq War. He Vietnamese had ‘layers’ of air defences, beginning with radar guided SAMs that ‘forced’ American planes to fly lower than they should, in range of the second layer of air defence, with traditional anti-aircraft guns. And then you had a final layer which was just soldiers firing upwards with their rifles and handheld machine guns.

The Vietnamese also had a first-rate airforce that forced the Americans to retrain and reequip some of their planes – the kill ratios were too low, compared to US experience in Korea and WWII – even though the Vietnamese planes were technically inferior. (The Vietnamese also took out American ships bringing planes with them, in their South Vietnamese harbours!) The Vietnamese also beat the Americans in the intelligence war, and that’s critical for anticipating somebody’s moves and so outsmarting them. Our problem here in the Arab world, apart from overconfidence and not studying things beforehand, is we assume that nobody can listen in to what we do behind the scenes, and assume that we also don’t have this capacity to spy on our enemies. Hence, the aforementioned paranoia.

Still, it’s a damned good novel and even Mr Eslam couldn’t get around the Vietnamese example!

Finally, I would add that chance itself is not the enemy of planning at all. It actually helps facilitate it because it gives you new opportunities you can use to your advantage. It’s just a question of being prepared for different eventualities and to have different plans in store and discern new and decisive variables as they emerge. Or as the Chinese say, the word for crisis is the same as opportunity. In Chinese at any rate, and look what they’ve been able to do up against the Americans, and the Vietnamese before them!!