The artist is constantly engaged in writing a detailed history of the end because he is the only person aware of the nature of the present. --- Wyndham Lewis

I don’t know if you know this, but I recently participated in a sci-fi and fantasy convention in Croatia, virtually, of course, on 8th FantaSTikon, 28-30 October 2022. I was the ‘Guest of Honour’ in point of fact.

By Emad Aysha

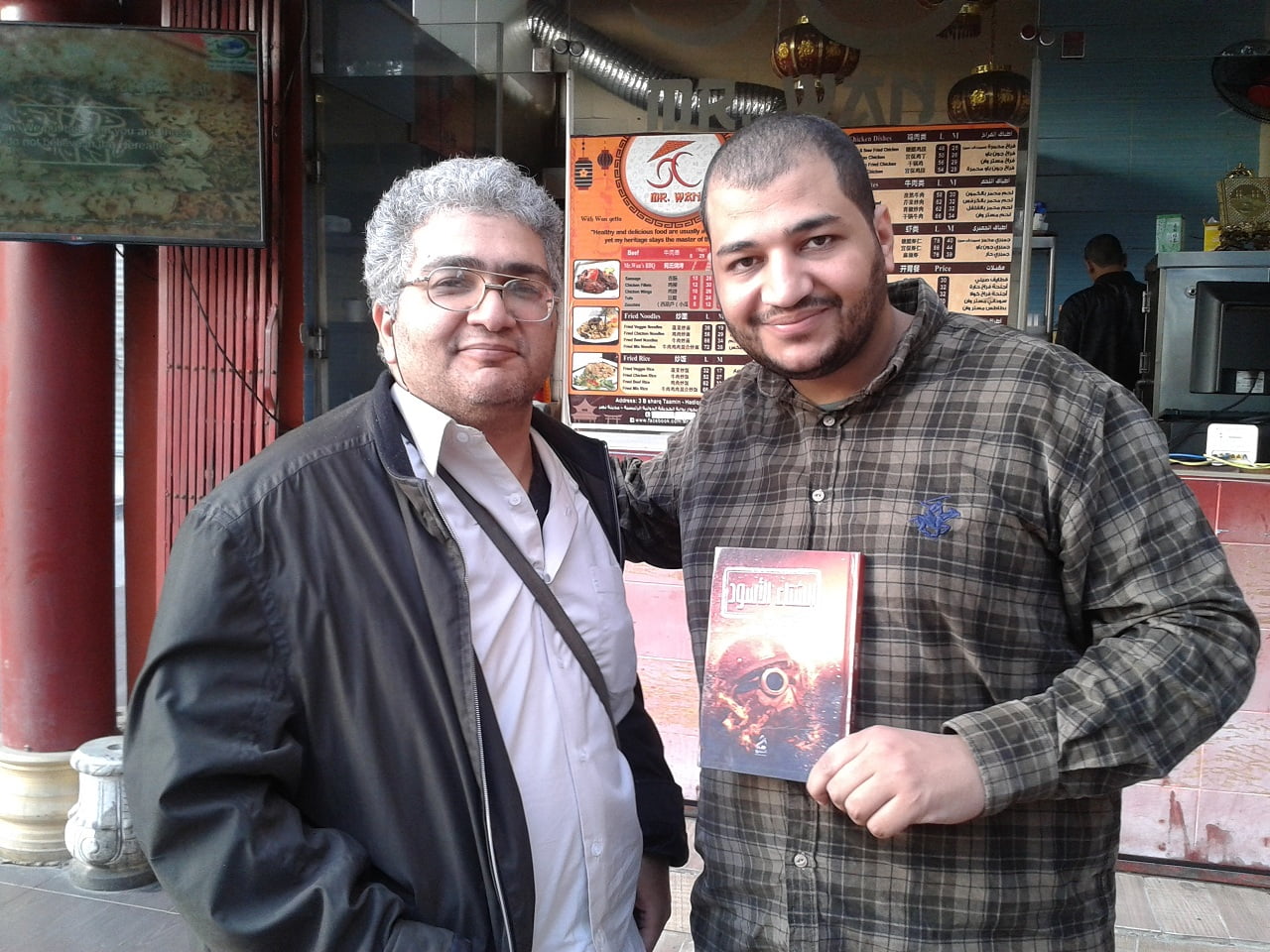

I had two joint sessions – “Egypt In Translation: SF, Antiquity and Metaphorical Communication” (with Dr. Ola Elaboudy, who had to be excused at the last minute) and “Post-Apocalypse, Egyptian Style: A Future Informed by the Past” (with Ahmed Salah Al-Mahdi).

My overall thesis was that Egyptian science fiction, and I suspect Arabic SF, in general, is informed by the past. As I argued in the post-apoc lecture, Arabs and Muslims don’t see the progression of time in the same way Westerners do.

We don’t have words like Medieval and Middle Ages originally in our lexicon, and we don’t see history as a straight line upwards. Famously, since Ibn Khaldun, we’ve had a cyclical model of history, and in the here and now, we’re enamored with going backward to our Golden Age.

More substantively we understand that cruel and tyrannical, when designating social orders, doesn’t necessarily mean primitive. Tthe Mamluk era was as cold as you like but a very prosperous and powerful period because of how thoroughly functional the system was.

You saw this in Ahmed al-Mahdi’s post-Apoc, steampunk novel Malaz: the City of Resurrection, the focal point of both lectures, since the military caste of warriors that rules the city of Malaz, the so-called Sayyadin or Hunters, are very explicitly modeled on the Mamluks.

That’s saying nothing of the even more advanced city to the south, Abydos, where the ancient Egyptian gods have been dusted off and, with that, the reign of Pharaoh and the ancient Egyptian priesthood. You can see it even more clearly, the logic employed in constructing these worlds, when the rebel Prince Seya explains why the southerners are so enamored by the ancients.

Look at the ancient monuments, how they weathered storms, and the nuclear war that brought on this apocalypse. They must have been preserved by the will of the gods they were built to glorify, so it’s second nature for people to start worshipping these gods all over again. As I said, the future is informed by the past. Resurrection is the appropriate word.

I’ve detected hints of this love of history in other Arab-Muslim SF writers, such as Abdulhakeem Amer Tweel, from Libya. He’s a big fan of the old Tripoli of the 19th century, when it was a capital of a small naval empire and a cosmopolitan metropolis ruled by the Qaramanlis – of Turkish ancestry – and sported its own Protestant cemetery. You can detect this in his story “The Most Powerful Weapon,” where you have a besieged city-state at the bottom of the ocean floor, and also in the opening scene where you have a floating space city, the worst dregs of the universe there, from all alien races and human nationalities.

His showcase story, “A Problem of Faith,” is in Libya. Put the setting for the events; a mosque involves holographic projections of forests and gardens in addition to the lovely architecture on display so that you can tell its harking back to the Andalusian epoch in Islamic history—our golden age by consensus.

But what about our past before Islam? There’s some of that in Malaz, true enough. Still, it’s not the focus of the story, and despite the clean streets of Abydos, its’ clear these people are slavishly devoted to their priests. In contrast, the priests hate all foreigners and whip people up into a frenzied holy war against the northerners.

As for other Egyptian writers, it’s a mixed bag. When they portray the ancient Egyptians nicely, they always go out of their way to insist that these guys were monotheists all along and that their science was just as advanced if not more advanced than the world of today, making us feel good about ourselves in the present where we aren’t nearly progressive enough.

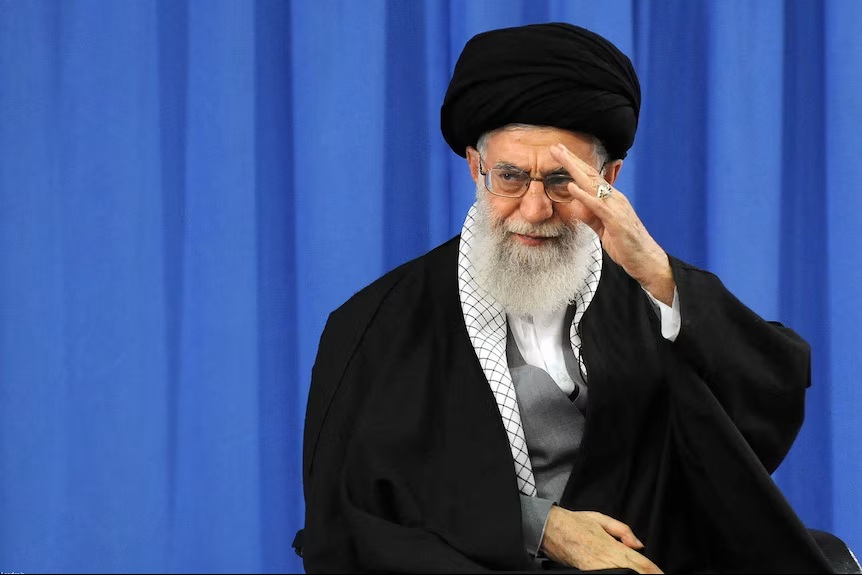

Looking further afield to Iranian science fiction, you find a glorification of past accomplishments – civilizations and empires – but a cyclical reading of history that also believes in human progress. I found this very strikingly in the short stories of Mr. Iraj Fazel Bakhsheshi. In “Yalda,” you have an account of cave dwellers of eternal gloom and winter as the Angels of Light fought a pitched battle against the Demons of Darkness – almost a nuclear winter.

The problem gets resolved, but even so, a young man and woman (an Adam and Eve duo) want to help the angels beat the demons, not content to wait it out forever. In “New Day,” you have discoveries about how the Ice Age came to an end that kowtow with a recent archeological find about the old Persian gods and how they exploded the ice and brought the sun’s warmth back.

Prehistory is notoriously absent in Arabic sci-fi, and even when it pops up, it feels like imitation, taken from Chariots of the Gods-type scenarios. We have our history to draw on as Arabs but no older creation myths that we can suffuse into science fiction. Consequently, you get a very different model of progress, with cosmological, theological, and environmental forces holding men back or releasing their full potential.

In Iranian SF, you don’t feel that all we’re doing as a race is re-accomplishing what we once accomplished in the past. In a word, evolution as in Mr. Iraj’s “The Beginning of Life,” where a nominally alien race alters Earth chemically to seed life, taking wormhole trips to check on the progress of their plans over the epochs. Till they have to crash-land on the planet, that is.

If you don’t have a past, you don’t have a future, the saying goes, and we have a ‘gap’ in our understanding of our past as Arabs. And it shows up in our science fiction. Thank heavens everyone else at the conference was speaking Croatian!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks to Marko Mlinar, from Croatia, for contacting me and giving us this tremendous opportunity to compare notes across cultures and times.

Please also see Abdulhakeem Amer Tweel’s “Libyan SF: A Short Story in the Making,” ‘Arab and Muslim Science Fiction: Critical Essays’, (McFarland, 2022), pp. 39-46.

Even more sci-fi here at my website: https://emad-sci-fi.my.canva.site/